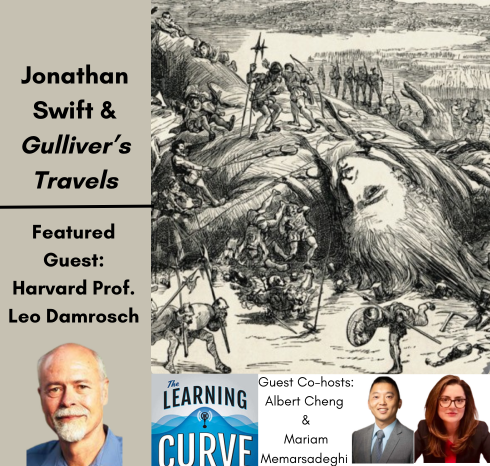

Harvard Prof. Leo Damrosch on Jonathan Swift & Gulliver’s Travels

/in Education, Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

Leo Damrosch on Jonathan Swift, November 15, 2023

[00:00:24] Albert: Hello everyone, this is Professor Albert Cheng from the University of Arkansas, guest co-hosting again this week on this week’s episode of The Learning Curve. I want to welcome you to the show and I want to welcome my guest co-host, Mariam. Mariam, welcome to the show. I think you’re a friend of the show, and you’ve been a guest co-host before, right?

[00:00:43] Mariam: Yes, Albert, great to join you today. I have been on as a guest co-host a few times now. It’s always a pleasure to work with Pioneer Institute. Focused on promoting democracy in my birthplace, Iran, using civic education, curricula, and resources as much as possible to get them inside the country. So, I really look forward to our show today.

[00:01:08] Albert: Great, great. Yeah, and going to have Professor Leo Damrosch from Harvard talk about his work on Jonathan Swift and Gulliver’s Travels, one of the great English satirists and certainly a lot of social commentary and political commentary that he gave in his time might be, is relevant today.

[00:01:24] Albert: So, yeah. I’m sure there’ll be some connections. I want to start off with some news, Miriam. So, growing up I don’t know if you went to high school here — did you have to take a high school exit exam?

[00:01:35] Mariam: I did go to high school here in state of Maryland, in Frederick, Maryland. I did not have to take any kind of exam, no.

[00:01:43] Albert: I didn’t either but actually I have a cousin who was three years my junior and he had to take the California high school exam. So, I always found it curious that I just missed the cut of having to take that high school exit exam. My cousin did. And of course, my two younger sisters had to as well. But I bring that up because the New York Times has an article from this week talking about some developments with the Regents exam. And I don’t know if you know, but the Regents exam is a series of high school exit exams that all students in New York have to pass in order to get a high school diploma.

Mariam: Yes.

[00:02:22] Albert: And it looks like this is now ground zero for the next debate on high school exit exams. I don’t know if you’ve been keeping track, but lots of states have been getting rid of their high school exit exams. I know California has a few years ago. And so, this is certainly a subject of great debate. And so, you know, I’d encourage listeners to check out the article and, and see what’s going on there.

[00:02:44] Mariam: Well, I think anything that, anything that can reintroduce rigor and a sense of expectation for performance is good. I’m not sure in particular if I don’t know enough about the exit exams to know if the [00:03:00] impact learning and if they provide incentive.

[00:03:02] Mariam: But it seems to me that tests aren’t necessarily always the best way to do that. But in an overall sense, I don’t think we have enough that. Allows us to, measure and motivate students across the board in a universal sense to acquire knowledge, to be able to apply it.

[00:03:21] Mariam: We’ve talked on this show many times before about how we’re lagging — we’re lagging compared to where we were ourselves not too long ago, and we’re certainly lacking when it comes to how we compare to other countries that are democracies, including countries that aren’t necessarily very well off economically, but are outperforming our schools. So, that’s really concerning to me.

[00:03:45] Albert: Yeah. Yeah. Well, anyway, let’s keep an eye out for what happens in New York. You know, it’s probably the next domino to fall or it looks like, but who knows what the future of exit exams will hold.

[00:03:58] Mariam: Yeah, yeah, I’m not sure we’re serving our students by getting ways to hold them accountable for their learning. And also the teachers to have a real way to know who are the good teachers, who are the not so good teachers. Rather than just, a mush kind of a situation. Yeah, yeah. To know. what caught my eye this week um, is a long, long piece and fascinating in the Atlantic called “How Reconstruction Created American Public Education.”

[00:04:26] Mariam: About how free people and their advocates persuaded the nation to embrace schooling for everybody. Really are I mean, I think it’s a big contribution to the world that the United States has made certainly other countries in Europe I know so pursued it, but it’s one of the big achievements of our of our country and that achievement is rooted in the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, reunifying, reintegrating not just freed slaves and their children but also poor white people from the Southern states and the idea that by educating everybody and not just the elites of society we can create citizens and bring everybody together into one coherent nation. And I was really struck by the rapid transformation of the South as far as schooling goes and how much that kind of energy is something that, you know, we’re capable of as a country and that without teaching it, without teaching, in fact, the history of education in our schools, that even a lot of our teachers don’t know, probably — history of education is without teaching that history, it may be that we don’t have a sense of all the really aspirational things that we can do in the future. You know, this is a country that has been able to overcome enormous, enormous adversity through good ideas and in good execution of good ideas. So, highly recommended. It’s in the Atlantic. It’s written by Adam Harris.

[00:06:05] Albert: Great. Yeah, I’ll have to check that out just to brush up on my knowledge of that. I mean, it is typically we I always think of Horace Mann and the common schools movement from the 1800s, but there’s way more to the story it seems like. Coming up after the break, we’re going to have Harvard professor Leo Damrosch talking about Jonathan Swift and Gulliver’s Travels.

[00:06:46] Albert: Leo Damrosch is the Ernst Birnbaum Professor of Literature Emeritus at Harvard University. His books include Jonathan Swift, His Life and His World. Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award in Biography and one of two [00:07:00] finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in Biography. Other works include Eternity’s Sunrise, The Imaginative World of William Blake, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism, and The Club, Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age, named one of the ten best books of 2019 by the New York Times.

[00:07:21] Albert: Professor Damrosch is also author of Tocqueville’s Discovery of America and Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Restless Genius, a National Book Award finalist for nonfiction and winner of the Winship Penn New England Award for nonfiction. He earned a BA summa cum laude from Yale University, was a Marshall Scholar first class honors at Trinity College Cambridge, and received his PhD from Princeton University. Professor Damrosch, welcome to the show.

[00:07:49] Professor Leo Damrosch: Thank you very much for having me.

[00:07:51] Albert: So, let’s talk Jonathan Swift the early 18th century author of Gulliver’s Travels, the essay A Modest Proposal —which I actually remember reading in, way back in 12th grade. He’s quite the giant of English literature and one of the funniest satirists of all time. You wrote an excellent biography, Jonathan Swift, His Life and His World. Could you start off by giving us a brief sketch of Swift’s life, but also the age which he lived?

[00:08:18] Leo: Yeah, he was born in Dublin, in Ireland, in 1667. That’s three and a half centuries ago. His parents were English. And their church was Anglican, that is, they were from the 15 percent minority that governed Ireland. The 85 percent majority were Catholic and often spoke only Gaelic. He graduated from Trinity College, Dublin. He was hoping for a career in politics. And as a young man, he went to England and worked as what we would call a speechwriter. But the party that he was supporting fell from power, and he decided his best hope was a career in the Anglican Church starting out as a priest, which he was for the rest of his life which was very much a public career also, but his real hope was to become a bishop and the bishops then, and I believe still automatically have seats in the House of Lords.

[00:09:07] Leo: So that would have made him in fact, a political player if he’d ever reached that position. In 1713 — and by then he was 46 years old — it became clear he was never going to get anywhere in England. We’ll talk about that later. He did get appointed Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. The Dean is like second in command to the bishop of the diocese. And it was a very important position. He was a brilliant administrator. He became a champion of the poor. And as I’m sure we’ll talk about also a champion of the oppressed Irish people. So, by the time of his death he was really regarded as a national hero in his native Ireland.

[00:09:44] Leo: Ireland was not part of the United Kingdom in the way that Scotland was. It was still treated as a colony, just as much as if it was Jamaica or Massachusetts in those days. And one thing I want to emphasize is literature was never central to [00:10:00] his self-image. He saw himself as intervening in contemporary affairs and in moral and political issues and his masterpiece, Gulliver’s Travels, was published when he was almost 60, and by then he’s bitter at being on the shelf, he’s trapped in his native Ireland and he wants to be in England where the action is, he’s never going to be a bishop. He poured into it all of the things he’s been thinking about and he’s been being angry about over the years, and well, it’s true, it’s very, very witty.

[00:10:27] Leo: It’s not a humorous book. It’s very, very acidic and biting. And he died in 1747. He was 77 years old and tragically for his final years suffered from advanced dementia. So, this person who was a powerful intellect ended up not even knowing who he was and being a kind of tragic figure.

[00:10:46] Albert: Yeah. Well, so, speaking of his criticism and his anger, the wit, and all the social commentary he gave — so, I’d like to have you talk about some of that. So, for instance, in your biography of Swift. You know, he wrote a lot of pamphlets on, on religion and politics.

[00:11:02] Albert: These include A Tale of the Tub and The Battle of the Books, The Conduct of the Allies. Could you talk about a few of the lessons drawn from Swift’s most famous essays? and actually related to that is he joined 18th century English poet Alexander Pope and, and politician Henry St. John Bolingbroke in skewering you know, Great Britain’s corrupt court politics, banking system and other things. So, can you just talk about some of the lessons drawn from his writing and his essays?

[00:11:31] Leo: Yeah. Really his lifetime was right in the middle of an age of transition where we would now say in hindsight England was entering the modern world.

[00:11:40] Leo: And there are a lot of things about the modern world he thought he understood and he really didn’t dislike. And one of them, to start with, was Conduct of the Allies, which only a specialist would read today, but it was a very potent book in its time. It was the war that was going on on the continent for basically global supremacy, the English general and hero was the Duke of Marlborough. And for his victories, England rewarded him by giving him Blenheim Palace, a huge edifice in England where he lived from then on. And Swift absolutely hated Marlborough. He saw him as a warlord, an imperialist, he thought England had no business trying to compete with France to see who could, well, it was really control the commerce of the world.

[00:12:22] Leo: And England spent the whole 18th century trying to do that. They ended up owning most of the subcontinent of India, just outrageously, sending out young administrators to govern an ancient civilization. Swift was deeply concerned about those things in a way that we now see as admirable as indeed another Irish patriot the next generation from his, Edmund Burke, fought heroically in Parliament for very much the same kinds of things.

[00:12:47] Leo: Two other books you mentioned are quite different, but they are certainly conservative reactions against the modern world. A Tale of a Tub and The Battle of the Books. regards most of modern literature in his day as self [00:13:00] indulgent, shallow, having lost touch with the deep wisdom of the past.

[00:13:04] Leo: But The Tale of a Tub got him into big trouble, and it really is what ruined his career in the Church because we’re not having a career, but I mean promotion in the Church, and that was bishops were appointed by the crown whoever is the monarch had the appointment of bishops. And unfortunately, Queen Anne read The Tale of the Tub and she hated it. It was supposed to be, and Swift thought it was a defense of the Anglican middle way by satirizing Catholicism at one extreme and radical Puritanism at the other extreme. But most people who read it thought he’s really satirizing religion itself. And this guy probably is a Christian, but not a believer.

[00:13:42] Leo: That’s not quite true, but it is true that he saw religion as a political instrument, much more than a spiritual one. And so, his skepticism really got him in permanent trouble. The other thing was the change in politics at that time. The modern idea of political parties emerged for the very first time at the end of the 18th century, our Founders thought there wouldn’t have to be any political parties and didn’t plan on that when they wrote the Constitution. And in England, it had divided into the Whigs and Tories, and I won’t try to explain at any length what they stood for, but basically the Tories were traditionalists who thought the source of power ought to be in the land, in people who had a stake in owning the land, whether they were aristocrats or just gentry, and the Whigs were on the side of commerce. You mentioned banking. Swift was of a generation that thought paper money was somehow not real, you know, like Monopoly money.

[00:14:39] Leo: You know, how could you accept the value of something that was only arbitrary just like the government claim to guarantee it and also the stock market came into existence for the very first time, which meant now there could be gambling on stocks that had nothing to do necessarily with the value of the institutions you were investing in, just your hope that they would appreciate. So he was [00:15:00] attacking all of those things.

[00:15:01] Leo: And the Whig prime minister of the party he hated was called Sir Robert Walpole, and he was really the first modern prime minister. That is, somebody who really did control an entire government apparatus, rather than just one guy among many, is sort of a spokesman for his cohort. And by modern standards, we would agree with Swift that government was pretty corrupt. But all government was corrupt in those days and what he could not grasp was Walpole was actually a great prime minister, and in all kinds of ways was doing things that were to the advantage of the English people. So, this was quite reactionary that way. So, we admire him for his attack on commercial imperialism. That’s absolutely you know, noble in him, but I think he didn’t kind of “get it” into the general progress of what was going on in history. He was an outlier and increasingly felt himself to be.

[00:15:54] Albert: Yeah, it’s fascinating to hear you explain the, just the historical context in which grew up what he was responding to. So let’s move on and talk about Gulliver’s Travels. The 18th century British dramatist John Gay wrote that it is universally read from the cabinet council to the nursery. and even just preparing for the show, I remember the Mickey Mouse cartoon that I, watched as a kid of Gulliver’s Travels.

[00:16:17] Albert: So, really for nearly 300 years readers have loved Swift’s witty fantastical fiction about the shocking and amusing shortcomings of human nature. Tell us what teachers, students, you know, and others should know about the larger themes in Gulliver’s Travels.

[00:16:33] Leo: Well, there was a lot of very targeted political and social satire that original readers would have picked up on that nobody would get today. And you would have to read a lot of footnotes from scholars to even guess that it’s there. But what made it great? Unlike A Tale of a Tub, which nobody reads anymore, even though it is a wonderful piece of writing, is that it actually works as a narrative. He started out trying to parody travel stories, which were very popular and were supposed to be all literally true in the genre, really, of truth is stranger than fiction.

[00:17:09] Leo: And he particularly despised Daniel Defoe, who just, I think, seven years before Gulliver’s Travels had published Robinson Crusoe, which is supposed to be the actual personal memoir of an ordinary sailor man with no particular literary gifts, and of course the whole thing is totally made up by Defoe. And it is a fantasy of complete self-sufficiency on a desert island all by yourself for 26 years instead of going crazy as a person would, as happens in Castaway when Tom Hanks goes crazy.

[00:17:42] Leo: It’s a fantasy of total self-sufficiency. But beyond that, he found himself just fascinated with creating a flying island that is held up by a load stone, a great magnet. Or what about tiny people, the Lilliputians or giant people, the Brobdingnagians. And he even made them on a perfect 1 to 12 scale.

[00:18:03] Leo: So, a Lilliputian is about six inches high and a Brobdingnagian is 12 times bigger than him. So, it’s all a kind of very realistic fantasy novel, which would have been an honor that anybody could recognize. And as you say the political satire, for example, in Lilliput, it has a lot to do with Walpole and his cronies, and there’s little in jokes, like, at one point one of the things they have to do is leaping and creeping, which is to basically grovel, you know, in order to get advanced in politics, or walking on a tightrope.

[00:18:33] Leo: But one guy falls off the tightrope, but he isn’t injured because he happens to fall on a cushion. And everybody knew he was talking about the king’s mistress and that was who saved him because she bailed him out. You know, so that’s footnote stuff. But beyond that, we really got the idea of the Lilliputians, they’re petty. They’re tiny. They’re short sighted. They’re all too much like our politicians. And in fact, they think, gosh, we’ve got this huge giant here, this guy Gulliver, [00:19:00] let’s let him go over and destroy the French fleet, what was called Blefuscu, but their rival, empire, rival empire, little HO-scale people, and kind of preposterous, and of course he won’t do it.

[00:19:12] Leo: Then in Brobdingnag, those people are giants, and so they are larger than us. They have wisdom and moral understanding that our politicians don’t and the King of Brobdingnag holding little Gulliver on the palm of his hand is asking him to tell about what things are like in Europe and so on and he’s more and more appalled at what he hears.

[00:19:32] Leo: And then Gulliver says, you know what, we have this wonderful substance, gunpowder, and I will tell you how to make that, you know, and then you’ll be able to destroy all your enemies. And the king says, from everything you’ve been telling me, your people must be the most pernicious race of little odious vermin that nature ever suffered to crawl on the surface of the earth. And anybody, you know, can see the power of that. You don’t have to know a thing about wigs and Tories.

[00:20:00] Albert: Yeah, yeah. Funny, you know, laugh at this and, really you, you’ve kind of, explained and, and shared how Swift painted it, this unflattering and humorous portrait of the island of Lily put and you know, life in its capital city Mildendo, is it?

[00:20:13] Albert: Yeah, it’s dominated by vain and acquisitive little people who rise in politics. I mean, you’re just speaking of some of the games that they played. How does Swift teach us to laugh at the human pride and folly that he’s, describing here?

[00:20:29] Leo: Well, I think it’s laughing because what else are you going to do? He spent his life trying to publish perfectly serious arguments in favor of various reforms and nobody paid any attention. And finally, you know, you just fall into what he agreed was misanthropic opinion of most of the human race.

[00:20:47] Leo: He didn’t mind being called a misanthrope. He said in a letter to actually Pope, his poet friend, he said, “I hate and detest that animal called man, but I love John, Robert, Peter, and so on.” That is, you can have a relationship with individuals who you respect that human race taken as a whole is pretty bad. And I’ve always thought he’s the kind of satirist who’s not just mocking things, you know, like some conventional political cartoonist. He’s really outraged at how human beings treat each other. And he’s a disappointed idealist. That’s what he is. We ought to be better than that. And I think his great successor is Mark Twain, who didn’t just write Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, but he really was a quite savage satirist of all kinds of things in his culture. And there’s a great quote from Twain, he said “I don’t care if somebody is a Christian or a Muslim or a Jew, all I have to know is he’s a human being. He couldn’t be worse!” And that is exactly what Swift would have said.

[00:21:49] Albert: Yeah, yeah, there’s definitely wisdom in those words. Mariam, you have some questions for Professor Damrosch.

[00:21:55] Mariam: I do. The American Founding Father, John Adams, wrote this about Gulliver’s Travels. He says, “There are not to be found in any library so many accurate ideas of government expressed with so much perspicuity, brevity and precision.” Professor, could you discuss Swift’s many political lessons, the flying Island of Laputa inhabited by narrow-minded scientists and Houyhnhnm Island, populated by philosophical horses and brutish Yahoos?

[00:22:30] Leo: Well, I wish we had some politicians who were as thoughtful readers as John Adams or Thomas Jefferson. Because of course the book is not a treatise on politics. It’s an analysis of where our values and assumptions come from at a deeper level. The flying island I mentioned is held up by a giant magnet. The people on it are abstract thinkers. They’re into scientific research very narrow minded, very unimaginative.

[00:22:57] Leo: But I’m sure what Adams is remembering is they are still the government for the ordinary people down below. And if ever there’s some kind of rebellion or trouble down on the land below, the flying island descends and squashes them to death. And it’s like an allegory of modern science. You know, it’s like when Oppenheimer saw the first atom bomb explode and said, he was quoting the Bhagavad Gita, “I’ve seen death, the destroyer of worlds.” That’s where science was going to end up. Of course, science is valuable in itself, but I think Swift also saw the way it gets used may not be. And the capital of that country that the island governs is called Laputa. Well, it’s the Spanish word for the whore. And if you know Dr. Strangelove, Stanley Kubrick called the Russian target that they’re supposed to bomb Laputa. It’s the same idea of technology gone insane. As for the horses, this is kind of interesting. \You studied Latin textbooks on logic if you went to Trinity College when he did. And somebody dug up his old textbook and it said homo est animal rationale, that is man is the rational animal.

[00:24:09] Leo: And just as a joke alternative, it said. Equus est animal hiniendi, which would mean the horse is the whinnying animal which of course isn’t a real word and Swift’s message is we’re not rational animals. He once said we’re sometimes capable of reason, but we are certainly not rational. So, what if it was the horses? So, what instead of thinking of a horse as a stupid beast of burden, you imagine them without all of our vices and that they really were rational. And so, Gulliver finds himself in a land where the people in charge are not people at all, but horses who are highly intelligent. But they literally don’t know what lying is.

[00:24:48] Leo: They have to call it “the thing which is not,” because they wouldn’t know how to tell a lie. Why would you do that? And their beast of burden are humanoids, who Gulliver realizes are all too much like himself physically, and maybe in other ways, too whom he calls the Yahoos, and that’s become a kind of generic word, but he made it up in Gulliver’s Travels, and what they do is constantly compete find out which one is the Alpha Yahoo, and the one who gets rejected, gets defecated on by all the others, and they, they like to fight over worthless little pieces of colored stone, which are the equivalent of jewels or money.

[00:25:26] Leo: In fact, they’re just like us. And the Houyhnhnms, the horses, sadly decide we’ve got to kick you out of here, Gulliver, because although you seem like a nice individual, we can see you’re nothing better than a Yahoo. So that’s not really about politics so much. It’s about how politics feeds on those competitive feelings and selfish feelings that are deeply ingrained in human nature. And in a sense, it was religious, you know, that we are finally defective the way Adam and Eve left us.

[00:25:55] Mariam: Fascinating. He was also a prolific and accomplished poet. He wrote clever, sharp, earthy rhymes. Some of these include a satirical elegy on the death of a late famous general, Stella’s birthday, March 13, 1727, and verses on the death of Dr. Swift, DSPD, among others. Can you tell us about some of his best poetry?

[00:26:22] Leo: Yeah, I think he’s a wonderful poet and he never gets the esteem he deserves because they’re not solemn, poetistical poems. They’re, playful and very colloquial. The rhymes are amusingly easygoing. Byron told Swift his rhymes beat us all hollow, they don’t feel forced at all. And they’re not meant to be high poetry, they’re meant to be playful, teasing commentary on life. Sometimes they’re angry satires, as you mentioned the satirical elegy on the death of the late famous general. That was Marlborough.

[00:26:55] Leo: And when Marlborough died, he had dementia, long before Swift did. And Swift thought that was about right, that people were, you know, just looking at this hulk of what had once been a hero. And the poem begins like this, “His grace, impossible, what, dead? Of old age, too, and in his bed. And could so great a hero fall? So inglorious after all.” I mean, it’s just full of bitterness about this guy that he hated. It led England into that war. But you mentioned the verses on the death of Dr. Swift, DSPD just means Dean of St. Patrick’s, Dublin. He’s imagining after his death what people will say about him when he’s gone.

[00:27:31] Leo: And they won’t be very sentimental about him. And yeah, he’s probably he’s run his race. I hope he’s in a better place. Like maybe he’s in hell instead of heaven. And I’m hoping that I’m not counting on it. It’s full of self-knowledge about how how other people regard you. Nut you mentioned the Stella poems. I think they’re among his most charming. nobody knows what she was, a life companion probably they were not sexually involved. They may even have thought they were related, although they weren’t supposed to have been and had possibly even a common father. All of that I go into in some length in my book.

[00:28:04] Leo: Because it’s a puzzle that he himself kept as secret as he could. But at any rate, they were very close. She moved to Ireland when he went back there to be Dean of St. Patrick’s, and they didn’t live together, but they saw each other every day. And I’ll just read to you one little Stella poem.

[00:28:18] Leo: Every birthday he would write her a poem. And this one, it’s 1717, that’s when he mentioned she’s turning 34. Actually she was 36, but he pretends not to know how old she is, and they’re both putting on a lot of weight. So, listen to the way the word size keeps coming up in this poem: “Stella this day is 34, we won’t dispute a year or more, however Stella be not troubled, although thy size and years are doubled, since first I saw thee at 16, the brightest virgin of the green, so little as thy form declined, made up so largely in thy mind — which is a wonderful compliment. Your mind is the real Stella — Then he goes on: Oh, would it please the gods to split [00:29:00] thy beauty, size, and years, and wit? No age could furnish out a pair of nymphs so graceful, wise, and fair. With half the luster of your eyes, with half thy width, thy ears, and thighs. And then, before it grew too late, how should I beg of gentle fate that either nymph might have her swain to split my worship too, in twain? People would call Swift, your worship, well, split me in half, this big fat man, and there’ll be two of me to go with the two of you. It’s really quite a lovely poem and shows that deep, intimate friendship that she will get it and won’t feel insulted by it.

[00:29:36] Mariam: Right, right. In his Modest Proposal, 1729, he mercilessly mocked Britain’s heartless 18th century policies towards Irish Catholics and the poor. Could you discuss this essay and how it shaped moral outrage, colonial injustices and ultimately impacted the national consciousness of Ireland.

[00:29:58] Leo: Yeah, he had already done some [00:30:00] political tracts before that that had great influence. I haven’t got time to talk about now, but this was his masterpiece. Ireland was expected to produce, in fact, required to produce raw materials, but not finished products that would be sold for a decent profit. They could sell wool to England, but the weaving had to be done in England. And at that time, the discipline of economics was just being born. And the pioneer economists were accused, the way later ones have been, of being totally rational in interpreting human motives and society. And in the 19th century, that would turn into laissez faire theory, in which the injustices of the factory system couldn’t be changed because that’s the iron laws of the market.

[00:30:42] Leo: And in fact, if you know the great famine of the mid-19th century in Ireland, millions of people were starving to death. That’s when there were huge emigrations to America and elsewhere because there was a blight in the potato harvest, which was what they lived on. But these were farmers who grew wheat, but they couldn’t use their own wheat because the landlord was giving that to his English, you know, buyers. So, they were starving to death in the midst of plenty because of the iron laws of the market. Swift absolutely denounced that kind of exploitation. And one of the things that economists were doing was issuing what they called proposals, one or another scheme to deal with the problem of rural poverty, which never did really deal with it. So, A Modest Proposal pretends to be a totally straightforward economic tract. And you have to read two or three pages before you think, wait a minute, this can’t be right. So, it’s saying that I’ve been studying this problem and how they’re all these starving beggars in the streets and roads of Ireland.

[00:31:43] Leo: And I have a solution for that. And the solution turns out to be England is basically eating up Ireland. So why don’t we just raise Irish babies for the table? And it goes on explaining in a very unemotional, rational way how you would breed them and cook them and all the things you could do and maybe make gloves out of this skin afterwards and so on. And it’s just a horrifying piece of work because it’s so deadpan, because it’s impersonating an economist who has no moral heart at all.

[00:32:12] Leo: And Swift is, as we’ve been saying, by the time of his death was a national hero in Ireland as a spokesman for the entire country and not just the Anglican minority he came from. And it’s absolutely right that he was a figure of enormous importance in the Irish consciousness.

[00:32:30] Mariam: So, he died in 1745 and is entombed at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin where he was dean from 1713 until he died. His epitaph reads “Here is laid the body of Jonathan Swift, Doctor of Sacred Theology, Dean of this Cathedral Church, where fierce indignation can no longer injure the heart. Go forth, Voyager, and copy, if you can, this vigorous, to the best of his ability, Champion of Liberty.” Professor, would you close by discussing Swift’s final years, his legacy, and what you hope teachers and students alike will remember about this hilarious literary genius?

[00:33:13] Leo: Well, hilarious, yeah, but the original epitaph is in Latin, of course it’s a quote from a Latin Roman poet Fierce indignation is saeva indignatio, savage indignation.

[00:33:25] Leo: And this is a guy who’s, like Mark Twain, is just furious at the way human beings treat each other. And who believes in liberty, even though he thought the Irish people are all too willing to just do what the English want them to, and they’re paying no attention to him. So, I think his legacy is moral indignation more than anything. There’s other people we read for laughs. And even, not so much as a satirist. I think it’s in the tradition that George Orwell would be a truth teller trying to understand what goes on in society and make people recognize what’s wrong with it.

[00:33:59] Mariam: [00:34:00] Great. And I think you have a passage that you can read for us. Is that right?

[00:34:04] Leo: Yeah, sure. Just a paragraph from the introduction to my biography of Swift: “Swift still matters three and a half centuries after his birth, because he was a great writer and a great man. If his political views were sternly conservative, it was because he feared anarchy in a turbulent era, and also because he was tempted by anarchic impulses within himself. His was a restless personality, embattled in what Sir Walter Scott called the war of his spirit with the world. And because he could empathize profoundly with the mistreatment of others, he became the hero of an oppressed nation. What made him great was a resolute character and a probing, lucid intelligence. Looking back 50 years after Swift’s death, a philosopher convincingly called him perhaps the man of the most powerful mind of the time in which he lived.”

[00:34:58] Albert: Professor Damros, thanks for sharing your expertise on Swift. I, I really enjoyed learning a lot more about him and, and his work.

[00:35:04] Leo: My pleasure. Thank you very much.

[00:35:31] Albert: Okay, and now we have our Tweet of the Week which comes this week from our friends at Education Week. That’s a lot of weeks in the sentence! So, Miriam, there’s this really interesting article that’s out, and it’s the top 10 most hated buzzwords according to teachers and school leaders, and so it looks like Ed Week did this poll and collected essentially buzzwords that teachers are sick and tired of. Any guesses on what made the list?

[00:36:03] Mariam: Common Core? I don’t know.

[00:36:07] Albert: That’s not a bad guess. You know, incidentally, at the beginning of the show, you mentioned the word rigor, and unfortunately, that made the top ten list of buzzwords that teachers can’t stand. So, look, I mean, I guess we’d have to really dig into the poll to figure out what’s going on. But unfortunately, that was one of the words, actually, that was the number one least favorite word from this poll — rigor. Number two is social emotional learning. So, I don’t know if that’s surprising to you, but it seems that word’s now getting overused and at least the teachers are, are getting sick of it, so, Anyway take a look at that article. You can see the top 10 list. And as a bonus, they even list the next 10. So, you can go from 11 through 20 to see what those — the top 10, top 20 buzzwords that teachers and educators can’t stand.

Mariam: Sounds good. All right.

[00:36:57] Albert: And that takes us to the conclusion of our show this week. Miriam, it’s been a pleasure to have [00:37:00] you guest co-host with me. Glad to have you on.

[00:37:02] Mariam: It was a pleasure. What a great show.

[00:37:04] Albert: Yeah, likewise and tune in again next week. We’re going to have Nina Rees, who is the president and chief executive officer of the National Alliance for public charter schools Until then be well, and I’ll see you next time.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Prof. Albert Cheng of the University of Arkansas and Mariam Memarsadeghi, interview Harvard Prof. Leo Damrosch. Delving into the life of Jonathan Swift, Prof. Damrosch explores Swift’s satirical brilliance in works like Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal. Analyzing his sharp critiques of politics and society, Dr. Damrosch emphasizes Swift’s enduring literary legacy, showcasing his wit, keen insights into human nature, and commitment to liberty. In closing, Prof. Damrosch reads from his book, Jonathan Swift: His Life and His World.

Stories of the Week: Prof. Cheng discussed a story from The New York Times which highlights New York considering reducing the importance of Regents exams in its high school graduation requirements. Mariam addressed a story from The Atlantic exploring the roots of more universal education in the U.S., tracing its origins after the Civil War to Reconstruction and highlighting the impact of education in bringing together diverse populations and fostering national unity.

Guest:

Leo Damrosch is the Ernest Bernbaum Professor of Literature Emeritus at Harvard University. His books include Jonathan Swift: His Life and His World (2013), winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography and one of two finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in biography; Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake (2015), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in criticism; and The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age (2019), named one of “The Ten Best Books of 2019” by the New York Times. Professor Damrosch is also the author of Tocqueville’s Discovery of America (2010) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius (2005), a National Book Award finalist for nonfiction and winner of the Winship/PEN New England Award for nonfiction. He earned a B.A. summa cum laude from Yale University; was a Marshall Scholar, first class honors, at Trinity College, Cambridge; and received his Ph.D. from Princeton University.

Tweet of the Week:

Here are 10 buzzwords that teachers can't stand.

Which ones have we missed?https://t.co/VTicX10K5y

— Education Week (@educationweek) November 15, 2023