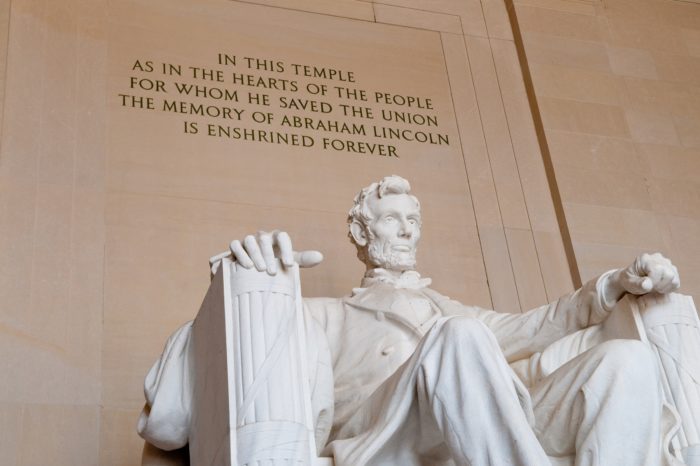

150 Years of Lincoln’s New Birth of Freedom

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address, American historical texts whose significance far exceeds their immediate practical impact, fundamentally transforming the moral purpose of the Civil War.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address, American historical texts whose significance far exceeds their immediate practical impact, fundamentally transforming the moral purpose of the Civil War.

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863 in the third year of the war (though it was announced shortly after the Battle of Antietam in September, 1862) states: “That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

[message_box title=”Join Us on April 2nd” color=”blue”]Fee public forum featuring Pulitzer Prize winning Civil War historian James McPherson. Join us in Boston on April 2nd at 8 am. Light breakfast will be served. Great panel discussion moderated by the Wall Street Journal‘s David Feith. Sign up today and share this link: conta.cc/XR6vVf[/message_box]

As many have noted, the Proclamation did not end slavery, since it did not apply to the slave-holding states that were not in rebellion, and could only be enforced in those Confederate states which were under Union control. Universal abolition would come only after passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. But it did provide hope for the millions who were enslaved, and for their abolitionist supporters. It also enabled black men to enlist in the Union Army and Navy; by the end of the war, nearly 200,000 did so.

Two years in, the Army of the Potomac had suffered humiliating defeats at Second Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville, where General Lee out-flanked the Union army in May. But the Vicksburg and Gettysburg campaigns during the summer of 1863 turned the tide of the war. General Grant reclaimed the Mississippi River for the Union, and General Meade thwarted General Lee’s attempted invasion of Pennsylvania at Gettysburg. The defeat at Gettysburg, which resulted in Lee’s retreat to Virginia, and at Vicksburg, which wrestled control of the Mississippi from the Confederacy, had the South playing defense for the rest of the war, considerably reducing Confederate hopes of victory.

The Gettysburg Address was delivered several months later, on November 19th, at President Lincoln’s consecration of the National Cemetery, where thousands of soldiers had been laid to rest. In a speech noted for both its brevity and unmatched eloquence, President Lincoln called for “a new birth of freedom,” a renewed commitment to the principles enshrined in the Declaration of Independence:

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us–that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion–that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.

Through both the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln made it explicit that in addition to preserving the Union, soldiers were fighting for the liberation and equal rights of all Americans. For that noble cause, hundreds of thousands of Union soldiers gave their lives.

Over the last several years, Pioneer Institute has promoted US History instruction in K-12 schools, to ensure that our children will learn about their national heritage, including the sacrifices that our men and women made in the Civil War, and in the long journey to ensure liberty and equal rights for all Americans.

Pioneer has held many events and published numerous op-eds urging a renewed commitment to teaching history and civics in our schools, and the addition of US History as an MCAS-tested subject and graduation requirement, in accordance with state law. You can read some of our related op-eds on the War of 1812, the US Senate, Native American history, and more.