The Confounding Massachusetts Estate Tax

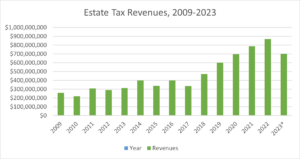

Massachusetts is one of only 17 states to levy an estate tax – a tax on the transfer of one’s property and assets after death. As shown in Figure 1, revenues from the tax have steadily increased, making it the source of a larger portion of the state’s total revenue over time. Since 2017 in particular, the tax has seen substantial growth with revenues increasing 158 percent – from $336 million to $868 million in six years. This incredible growth has made the estate tax the state’s 20th top source of revenue in 2021 – jumping eight spots since 2017.

Figure 1: Estate tax revenue from 2009 to 2023, from Pioneer Institute’s MassOpenBooks website. *Note: Data for 2023 is incomplete due to the ongoing fiscal year.

Why has the estate tax grown so much in recent years? One likely explanation is the significant growth of personal property values in the state. The estate tax is levied on the fair market valuation of assets at the time of death or six months later, per Mass.gov’s Guide on Estate Taxes. The housing market, where the largest share of estates’ fortunes are typically held, has seen prices rise substantially in recent years. Thus, higher asset values may have led to a greater amount of taxable liability for estates and tax revenue.

Massachusetts’ Revenue in Context

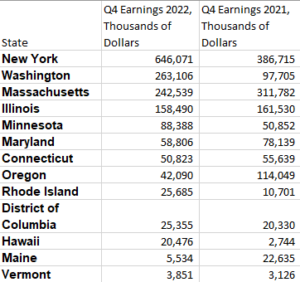

Figure 2: Estate Tax Revenue for selected states, from the fourth quarter of 2022 and 2021. Data comes from the Census Bureau. The table is ranked from highest to lowest revenues from 2022.

This growth is not merely an intra-state phenomenon: Massachusetts’ collections are remarkable when compared to other states that levy such a tax. Figure 2 shows that Massachusetts’ estate tax had the third highest receipts in the nation in the fourth quarter of 2022, and the second highest in the fourth quarter of 2021. Only New York realized more revenue from the tax than Massachusetts in both quarters. There is a considerable difference between Massachusetts’ revenues and those in other New England states: a difference of $216 million with Rhode Island and $198 million with Connecticut in the fourth quarter of 2022.

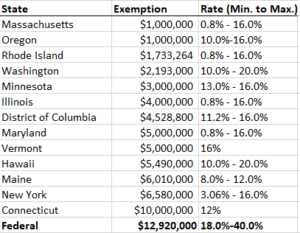

The reason Massachusetts out-earns other estate-taxing states is likely due in part to its low exemption threshold – the minimum valuation an estate can have in order to be taxed. Massachusetts and Oregon have the lowest exemption threshold in the nation at $1 million. Compare this to the median threshold of $4.5 million (including D.C.) and the federal threshold of $12.92 million.

Figure 3: Exemptions and rate intervals for selected states arranged from lowest to highest exemptions, according to statues on January 1st, 2023. The federal exemption and rate interval are inserted for comparison. State data sourced from the Tax Foundation (table 36), federal exemption sourced from the IRS, federal rates sourced from SmartAsset.

The threat of double taxation is another pressing issue facing taxpayers. The federal government used to offer a dollar-for-dollar credit on estate taxes up until 2001, allowing states to earn revenues without increasing the overall tax burden. However, tax reforms replaced this system with a deduction – leading many states to reform or rework their estate tax. Without state-level reform, Massachusetts residents with an estate valuation over the federal exemption face taxation at both levels.

These two factors contribute to the out-migration problem Massachusetts is facing. A state with such a daunting tax dissuades retirees, long-term wealth, and businesses from setting and growing roots in-state: instead opting to settle in a tax-friendlier climate, such as Florida or New Hampshire.

The Commonwealth must take steps to dissuade this out-migration. Reforming the estate tax would be a good start. Pioneer’s recent suggestion to increase the threshold to $2 million is a step in the right direction, but not enough. Raising the exemption around the statewide median – between or at $4 to $5 million – should be sufficient. While the estate tax is, without a doubt, a significant source of income for the state, policymakers must consider the long-term economic future of the Commonwealth.

Peter Mentekidis is a Roger Perry Transparency Intern with the Pioneer Institute. He is a rising senior at Providence College, with a major in quantitative economics and a minor in philosophy. Feel free to contact via email, linkedin, or writing a letter to Pioneer’s office.