MassDOT’s West Station design plans fall one track short

In 2014, MassDOT proposed the construction of West Station, a new transit hub in Allston-Brighton that would significantly improve the connectivity of Boston’s western suburbs with Cambridge and North Station. Using an old freight corridor called the Grand Junction Railroad, the project initially seemed like a neat work-around to the inevitably exorbitant costs and disruptiveness of the North-South Rail Link, at least for Framingham/Worcester Line users. Unfortunately, MassDOT’s recent designs for the station will potentially limit accessibility to new destinations and old ones alike.

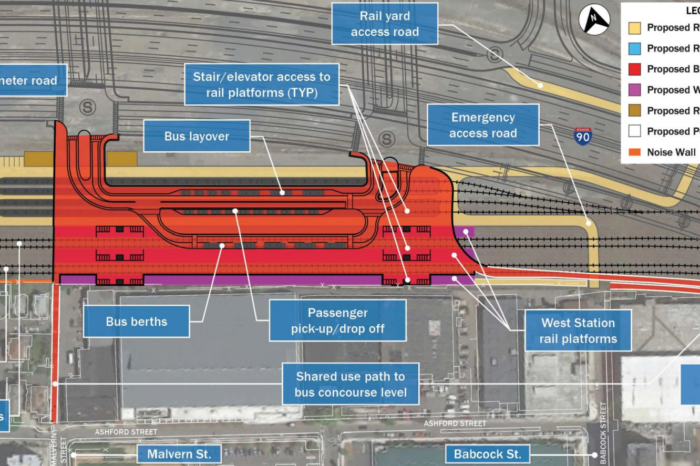

Instead of a four-track ideal that would accommodate both inbound and outbound travel on each branch, MassDOT wants to limit local Framingham/Worcester Line trips to a single track to accommodate two express trains that existing commuters would use to reach Back Bay and South Station. However, this design approach would severely hinder service on the new train line, making it impossible for local trains to pass each other without also disrupting the new Grand Junction connections.

Supposedly, the justification for this inconvenience is that a three-track option will prove less disruptive to existing commuters from Framingham, Worcester, and the surrounding suburbs. It’s true that, all else equal, adding stations to a train line will make commute times longer for current riders, and express trains help commuters from far-flung exurbs like Westborough and Grafton bypass less busy stations closer to downtown. However, some current design details of the Allston Multimodal Project are far less necessary than the elusive fourth track. These details include a spacious layover yard that allows commuter trains to remain idle during off-peak hours. As prolific transit advocate Alon Levy has pointed out, the layover yard at West Station would take up some of the most valuable real estate in the state while inhibiting air rights development over the Mass Pike. Removing the layover yard would also allow for more buffer space between a middle-class urban neighborhood (Allston) and a litany of noisy nuisances.

Moreover, commuters from the west who work in Cambridge or Somerville stand to gain much more in convenience and connectivity than others stand to lose. A big part of the appeal of a four-track option for West Station is that it maximizes accessibility to the station’s surroundings, which may eventually include office space, Harvard dorms, retail, academic buildings, open space, and housing. It’s not hard to imagine this new neighborhood becoming a desirable place to work for western commuters, especially given MassDOT’s projection of 12,300 new jobs in the Allston project study area by 2040, the year West Station is scheduled to open. These jobs will appeal to western commuters in particular, slicing between 10 and 15 minutes each way off of their peak-hour train trip to South Station. Thus, in the long term, prioritizing express tracks over local double-track platforms might prove impractical.

Contrary to the implications of MassDOT’s recent design plans, ensuring a modern four-track design for West Station’s local tracks would benefit MetroWest and Central Massachusetts residents. While the express tracks are an important step towards satisfying the interests of long-time commuter rail users, implementing them should not come at the expense of high-quality local service.

Andrew Mikula is the Lovett & Ruth Peters Economic Opportunity Fellow at the Pioneer Institute. Research areas of particular interest to Mr. Mikula include urban issues, affordability, and regulatory structures. Mr. Mikula was previously a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern at the Institute and studied economics at Bates College.