Fare-Free Public Transit in Boston: A Holistic View

Due to reduced ridership since the pandemic, the farebox recovery ratio for the MBTA is now relatively low. This measure represents “the difference between the revenue collected as user fares and operating expenses.” A ratio which is less than one represents that the agency is not profitable, and must be subsidized.

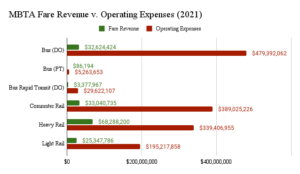

In 2021, the paratransit and directly operated buses (buses which are operated directly by the MBTA agency’s employees) had 2 and 7 percent farebox recovery ratios, respectively, and the rapid transit buses (buses which allow for their own separate right-of-way areas during peak hours and provide similar features as rail fixed guideway systems) saw an 11 percent farebox recovery ratio. The commuter rail had a farebox recovery ratio of 8 percent, the heavy rail had one of 20 percent, and the light rail’s was 13 percent.

In the wake of these low COVID-19 fare recovery levels, Chief Financial Officer Mary Ann O’Hara told the MBTA Board of Directors in February 2023 that they are “…very far away from pre-pandemic levels for fare revenue, and you can see that factor by reviewing the fare recovery ratio at 23% compared to fiscal year ’20 of 42%.” Fares no longer contribute as much to the MBTA budget, and they certainly do not come close to covering operating costs for each mode of transit.

Fig. 1. Data Sourced From: MBTA Analysis (2021).

Given that fares contribute minimally to the MBTA budget, many Boston politicians have begun to push for free public transportation fares. One of the most notable champions of the cause is Mayor Michelle Wu, who, shortly following her ascension to office in 2022, moved to extend a pilot program that had eliminated fares on one Boston bus route. The program used $8 million in federal funds to make the routes 23, 28, and 29 fare-free for two years. Following this action, Wu posted to Facebook expressing her satisfaction, stating that, “Public transit is a public good.”

Economist David Zipper states that free public transit offers benefits to society, “such as reduced emissions and traffic crashes, while also helping to achieve social goals related to equity.” However, he also argues that while it does offer many advantages, public transit is not actually a public good, cautioning against using that language to promote free fares.

Good for the public and public good are not necessarily the same. For something to be a public good, it has to be nonrival and nonexcludable, meaning that individuals cannot be deprived of the good once it is available and that its use by one person does not hinder another’s access. Public transit does not satisfy either of these requirements; therefore, it is not a public good, according to Zipper. While it makes sense for the government to subsidize public transport since it has positive impacts, it does not necessitate the service being entirely free for all passengers.

It is also important to note that free MBTA fares would not be very fair to those who do not use public transport. If fares were eliminated, the lost revenue would have to be made up for with tax money, which would likely come in the form of an increase in gas tax. To pay for those riding the bus or train for free, those who do not use public transport would have to shoulder the tax burden to pay for the lost revenue to the same degree as those who use it, which would not be fair to them. Instead, those who use the T or the bus and are able to pay should do so, so as to mitigate the lost revenue and maintain fairness.

Overall, Mayor Wu’s execution of a plan to eliminate fares from routes 23, 28, and 29 had positive impacts, as those routes run through low income communities where cost had previously deterred ridership for some residents. Using government subsidies to allow low-income communities to use public transit for free may be worth the cost to increase access. However, public transportation is not a public good and riders should therefore carry some of the costs to maintain the system from which they benefit.

About the Author: Sarah Delano is a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern at the Pioneer Institute for the summer of 2023. She is a senior studying Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.