What Janus Means for Massachusetts

In downtown Boston Monday there was a rally of a few hundred public union members, with a speaker roster that included U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey, among many other elected officials. The reason was that the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) was hearing oral arguments on the Janus v. AFSCME case.

The plaintiff in the case, Mark Janus, is a state child-support specialist in Illinois who had opted not to join the state employees’ union – AFSCME. He has asked SCOTUS to overturn a precedent from a 1977 case that allows public employee unions to compel non-members working in the public sector to pay union ‘agency fees’ against their wishes. Janus argues that compelling non-union members to pay union dues constitutes forced speech in violation of public employees’ First Amendment rights.

We are just past the midpoint of the SCOTUS term, and a decision in Janus could be issued as late as June. No one can be sure where the Court will go, but many observers believe that the case, because it touches on issues similar to Friedrichs v California Teachers Association, may find a similar alignment of the eight justices, who deadlocked 4-4 last year after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia. The deciding vote then would be new justice Neil Gorsuch, and most believe he will vote in the same way Scalia would have – for the plaintiff.

Despite much of the rhetoric swirling about the case, the significance of Janus is really about one thing—the First Amendment – and its protections of free speech and freedom of association.

Compulsion

Freedom of association means that an individual has the right to join a union. It also means that that individual has the same fundamental right not to join a union. The First Amendment ensures both sides of the freedom of association. Union membership should never be banned, but neither should support of a union be compulsory.

In general, federal courts are cautious when considering circumstances where the government may compel individuals to do things. For example, SCOTUS bent over backwards in its plurality opinion in NFIB v. Sebelius to avoid the constitutional issue of whether the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate was constitutional under the Commerce Clause, instead finding that it constituted a tax under Congress’s legitimate taxing authority.

Although the cases vary in their facts, the underlying philosophy of each remains consistent – compulsion by the government should be utilized sparingly and be subject to enhanced scrutiny by federal courts. Regarding Janus, our view is that no one in America should be compelled into membership of any group with which they disagree, let alone be forced to pay part of their salary to any such group.

Who’s the Free Rider?

Public employee union leaders have long accused members who want to leave the union of being “free riders.” As a result, they argue, unions must require all workers to be part of the union. After all, workers benefit from union activities to negotiate on their behalf for salary and benefits.

If that is all the unions did, then it is clear that union members who benefit from their work would in fact be free riders. But unions do much more than that, and in fact another perspective would argue that workers who are compelled to be part of a union and to pay full agency fees are “forced riders.” Given the high level of protection granted by the U.S. Constitution around freedom of association, why are workers compelled to be part of a union? Why are they compelled to support financially the expression of views with which many members disagree? Isn’t it their right to choose who they associate with?

A very good case could, in fact, be made that it is the unions who are free riding. Unions are the ones, after all, who have insisted on having sole negotiating power for everyone who works in a public setting. Such coercive power is not pre-ordained. For example, workers could choose to have no one negotiate on their behalf. They could choose to have new negotiators represent them rather than the monolithic public unions currently in place in most states; that is, there could be competition among unions and new unions that are created. One could imagine a full spectrum of unions. At one end would be the current unions, which negotiate on immediate financial interests and workplace quality, which curb management rights, which get deeply involved in politics and campaign contributions, and which assume positions on a range of issues unrelated to the immediate work environment of its members; at the other might be unions that are “stripped down” down to essentials and focus solely on the immediate financial interests of the members. With the range in services would be different levels of dues.

Public employee unions frequently message policy positions on a host of issues that aren’t directly tied to classrooms or the specific work of the union in question. (For example, animal rights, environmental, foreign, tax and other policies.) Union members are like all Americans in that their views on these and other issues span the political spectrum. Currently, there are people who are paying union dues who are coerced to pay for the speech of an organization that may not “represent” their actual views on one, many or even all issues.

While there is no very good summary data that I have been able to find on the political leanings of unions, most commentators suggest that between 20 and 50 percent of union members, depending on the union and the location, hold views substantially differing from those of their union. That’s a lot of people to disenfranchise.

So who’s a free rider? To my mind, a worker can rightly be called a free rider if he or she substantially agrees with the union and how it is using his or her dues (fees), but chooses not to pay his or her fees. A worker who does not agree with the use of the fees in any significant way and chooses not to pay the fees is by no means a free rider; in fact, in this case it is the union who is the free rider.

Abood and Obstacles

Janus is an important case because for years SCOTUS has had its eye on the previous Supreme Court decision, known as the 1977 Abood precedent. Janus is challenging the artificial distinctions, articulated in Abood, between institutional and member services fees and ones deemed to be for purely political purposes. Over the last five years or so, the Court has included language in its decisions questioning Abood’s arbitrary distinction in great part because it has proven impossible for members to distinguish how the funds are used.

Unions regularly give money to political candidates without allowing individual workers any ability to provide or withhold consent. Members may opt out of some of those payments through the so-called Abood precedent, but public unions often make life difficult for union members who do, including by purposefully complicating the opt-out process. Members shouldn’t have to choose between such obstacles and financially supporting political candidates they don’t like.

What Does Janus Mean for Massachusetts?

So, in Massachusetts, what happens if the court decides in Janus’ favor? Here are a few thoughts organized by impacts on people and institutions. As regards individual workers,

- There will be many who see the value of the unions’ manner of representation and will continue to support its activities.

- There will be a minority of workers who are truly “free riders,” again, people who benefit from the union and substantially agree with its activities, but who refuse to pay their fees.

- There will be a potentially large minority who believe that the unions need to demonstrate their value, open up to dissenting views, or change their stance on issues.

- There will be a minority of workers who simply want out of the union structure.

Institutionally, in a state like Massachusetts, which has long assigned value to the benefits of unions, there are likely to be the following impacts:

- The unions may be more open to dissenting views in their ranks. By incorporating new voices, these unions may be less strident in their politics or beholden to one or another political party.

- The unions may focus more on services to their members that will bring more immediate benefits, including salaries, benefits, etc.

- Unions will spend more time making the case that they have real value to their members and that free riding is not a good thing.

- We may see competition in the public union space. That is, a decision that favors Janus could open the path in Massachusetts to new unions that offer different kinds of representation, e.g., a more stripped down, focused representation of the members’ interests that eschews the overtly political – and often extraneously political— issues where unions are often engaged today.

There is a lot of hyperbole in the ether today on this case. The unions really should ask themselves why they fear a decision that favors Mark Janus. Do the unions really believe that there are so many unhappy union members? Do they believe that such a large number find their current offerings unattractive that they would opt out? That certainly does not speak to an organization confident of its ability to represent the interests of its members.

Parting Thoughts

This is a case that has been a long time coming. Janus percolated through the lower federal courts, SCOTUS accepted the matter (it accepts roughly 150 cases per year out of thousands of requests – so this is an important issue), and it was docketed for briefs and oral argument.

Pioneer weighed in on the basis of seeking to promote freedom of association and speech under the First Amendment – these were compelling issues to us. If we did not act, we would have missed a great opportunity to talk about something that is core to Pioneer’s mission.

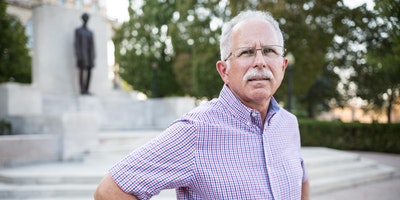

Jim Stergios is executive director of Pioneer Institute. Read his blog commentary here. Follow him on twitter: @jimstergios