Leslie Klinger on Sherlock Holmes, Horror Stories, & Halloween

/in Featured, Learning Curve, News, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

Transcript, The Learning Curve, Leslie Klinger, October 31, 2023

[00:00:00] Charlie: Well, hello, everybody, and welcome to this week’s edition of The Learning Curve. My name is Charlie Chieppo. I’m a senior fellow at Pioneer Institute, and I am pleased to be here this week with Alisha Searcy. Alisha, welcome.

[00:00:13] Alisha: Good to see you again. Thank you. Happy to be with you again.

[00:00:15] Charlie: Well, thank you. It’s my pleasure. So, let’s get started. We’re going to jump right into this week’s stories. And I’m going to start my story. This week comes from Chicago. And this is from Illinois Policy and it’s written by Paul Vallas, who is the former head of the Chicago Public Schools and a former Chicago mayoral candidate. The reason I chose this is because I have this ongoing fascination with how every time you see a poll, it talks about how know, the thing that, voters are most concerned about, particularly in the domestic area are education and healthcare, yet it seems to me that nobody ever [00:01:00] votes based on education, which I find astonishing and I don’t really understand.

[00:01:05] Charlie: So, anyway, this particular story is about how for the last couple of years the Chicago Board of Education has increasingly been approving charter schools in the city for two- to three-year contracts, instead of the standard five- to 10-year terms that had been there in the past. Now, for those of us who are supporters of charter schools, we’ve kind of seen this all before. You know, the reason this happens is because they, the opponents, are trying to promote instability in the schools and make it hard to raise money for improvements when you’ve got such a short term. It hurts enrollment. It makes it hard to recruit and retain teachers.

[00:01:44] Charlie: And the fact of the matter is that it appears that this is sort of the latest in a long list of the Chicago Teachers Union basically getting whatever they want, regardless of who it hurts. The Chicago Board of Education has already frozen charter enrollment until June of next year. They bar charters from using and converting former Chicago Public Schools’ buildings that were closed in recent years due to plummeting enrollment.

[00:02:13] Charlie: Think about that. In a city where crime is rising, you got you know, boarded up buildings are epidemic, the CTU would rather have these buildings empty then allow charters to use them to educate kids. Interestingly, not surprisingly, Chicago charters dramatically outperform Chicago public schools’ kids.

[00:02:33] Charlie: It’s not as if they’re creaming — 98 percent of the students at the charter schools are black and Latino, 86 percent of them are from low-income high schools. And so, given that, it’s pretty clear that these charter schools are essentially the only alternative they have to schools that are often unsafe and low performing. You know, but Chicago Teachers Union says no, and the city’s board of higher education goes along. [00:03:00] It’s one of those things getting back to what I said at the beginning, where you think it might matter come election day. But sadly, it probably won’t.

[00:03:07] Alisha: Yeah. So it’s interesting, right? Chicago is a thing in itself thinking about the fact that the new mayor is a teacher, right? So, it’s interesting to watch what’s happening in general in the city of Chicago. And I’m very curious to see what will happen in terms of its education system and what happens in the city. And as you, you know, alluded to this direct connection to. crime and what’s happening in the community. And I’m also a former charter network leader, i.e. superintendent here in Georgia, the way that our state charters are set up. And so, you’re right, Charlie, as someone who’s run charters and had to turn them around, I had one school that had a three-year charter. I came in in its third year, and so there was nothing I could do to turn the school around, you know, the damage had already been done.

[00:03:54] Alisha: And so, what I’ve learned the hard way as a policymaker is You can have the best of intentions and get good policies passed, but sometimes when in practice, you know, practices are put in place that really put barriers in place, no one is successful at the end of the day, it really just hurts kids.

[00:04:14] Alisha: So, I hate to hear that and I’m glad at least that these issues are being raised, but I hope that adults will come together and do what’s in the best interest of kids.

Charlie: Amen.

[00:04:33] Alisha: So, on that note, speaking of polling, my story of the week is a new place to learn civics, the workplace. And this was in the New York Times written by Melissa Eddy. And so ironically, when we talk about polling according to the Pew Research Center, only 17 percent of Americans trust officials in power in Washington to do the right thing, but business is viewed as the one institution that is both ethical and competent, according to Edelman Trust Barometer.

[00:04:54] Alisha: And so, this article is about the workplace, i.e. business being the place where workers are learning about democracy and civics. And so, this is interesting to me too, because this is on the heels of a panel we just did last week on the book Restoring a City — on U. S. History and civics in America School.

[00:05:16] Alisha: I hope I said that right. And so, this whole notion that, I think since the ‘70s we have really gone backwards in terms of teaching civics in our schools where our young people — and I would even argue, not even our young people, adults, I’m in my 40s — have not read the Constitution, don’t know the Bill of Rights have never read the Federalist Papers.

[00:05:40] Alisha: Very important founding documents that really set, the course for this country. Obviously, there were things that were not done correctly and we’ve had some ugliness happen in this country, but we have a nation of Americans who don’t know who we are as a country, and it’s largely because we’re not learning it in our public schools.

[00:06:01] Alisha: And so, here this company in Germany has decided that they’re going to teach civics at work where people essentially sign up for this program and they learn things like media literacy, which has been a critical issue in Germany in particular. And so, while programs in America, according to this article, are frequently focused on teaching employees about how the government works and voting rights, which are certainly important in Germany, their basic premise is about empowering employees to understand how their actions, both in and out of the workplace affect political climate and ultimately their own jobs. And so, teaching them to question conspiracy theories and disinformation, aren’t we riddled in our country with all this disinformation? And, you know, you Google something and you have to check the source because you’re not really sure if it’s true.

[00:06:53] Alisha: Many of these stories now are clickbait, and so it’s misleading. So, I think it’s a brilliant business case [00:07:00] that Judith Borowski said managing director of NOMOS, that democracy is the basis of our entrepreneurial activity. And she says, if we no longer have democracy, Then the basis of our entrepreneurial activities will also be very curtailed.

[00:07:15] Alisha: And so obviously the most important piece here is we need to learn civics. We need to understand our democracy. We need to know how our government works. We need to know the importance of, of having a difference of opinions and not, becoming violent, right? And just being able to have dialogue and, share ideas.

[00:07:34] Alisha: That’s a part of who we are as a country. And then here we also have business understanding that you do good business when you have employees, right? Who can. have differences, whether it’s cultural differences, racial differences, religion, and now political differences who can work in the same place, have discourse, have dialogue be able to share and maybe learn from one another without it becoming politically charged.

[00:08:00] Alisha: And so, I think this is brilliant. I would love to sign up for this program myself, right? There’s so much to learn. But I’m hoping that in this country, that we move more in this direction. If we can’t get it in schools, maybe it is a nice idea to rely on business to help us get there.

[00:08:17] Charlie: Well, look, I think Alisha, we clearly need all the help we can get on this front. I think the thing that struck me, being from an older demographic than you are, is when you talked about all the disinformation and I think disinformation is very often particularly sort of disseminated through social media of an age where I still find myself having this reaction where I hear a candidate or a public figure, say something clearly wrong, you know, and lying and I think, oh, well, you know, he or she will pay a price for that and then I get away with that and then I catch myself and say, you know, no, the days of watching Walter Cronkite every night are over. They probably will get away with that.

[00:08:57] Charlie: And it’s just, it’s kind of jarring, you know? It is. You’re not used to it absolutely is. Yeah. Anyway, well that’s a good story. Thank you very much. Alright. Well after the break we will be back with Leslie Klinger, our guest this week, and I think that you’ll find him. To be a very appropriate guest for Halloween week, so we will be back right after this break.[00:10:00]

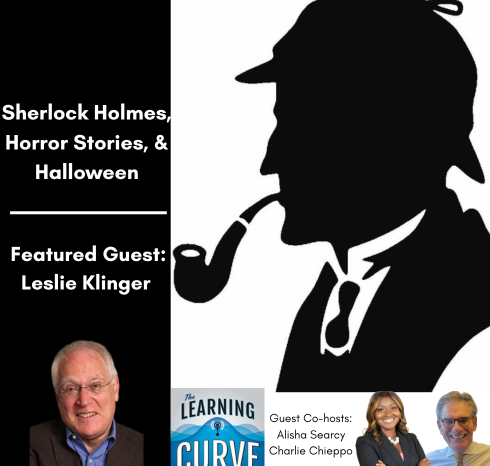

[00:10:13] Charlie: Leslie Klinger is considered one of the world’s foremost authorities on Sherlock Holmes, as well as being an attorney who specializes in tax, estate planning, and business law. He’s a writer, literary editor, and annotator of the classic horror fiction genre and history of crime, including the Sherlock Holmes stories, the novels Dracula, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the stories of H. P. Lovecraft, the Edgar-winning classic American crime fiction of the 1920s, as well as Neil Gaiman’s Sandman comics and American Gods, and Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons graphic novel Watchmen. He is currently the editor of the 16-volume Library of Congress Crime Classic series.

[00:10:58] Charlie: Les attended the [00:11:00] University of California, where he received an AB in English, and also earned his JD degree from the University of California Law School, then called Boathall, now known as Berkeley Law. So, we welcome Leslie Klinger.

[00:11:12] Charlie: All right, Leslie Klinger, Sherlock Holmes is among the most famous fictional figures of the last hundred plus years, while also being listed as the most often portrayed human literary character in film and television history. As the editor of the definitive new annotated Sherlock Holmes would you share with us a very brief thumbnail sketch of the British author of the 56 Holmes adventure stories and four novels, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle?

[00:11:38] Leslie: Well, so Arthur Conan Doyle was an Irish born, actually born in Edinburgh and didn’t come to London until fairly late in his life. When I say late in life, I mean after he had already created the Sherlock Holmes character based in London. But Conan Doyle was born in a Catholic family, he became a lapsed Catholic, he went to medical school at Edinburgh University, and there came under the influence of professors who taught him to be observant and meticulous in his diagnostic abilities. He would draw on these characteristics later in his writing, but he began to write as well. He was a born storyteller. He was always telling friends stories. He began writing them down and he struggled as a writer.

[00:12:33] Leslie: He, like most, sent around several novels to try and get them published. And he was successful with short stories. But in any event, he came up with the idea for a detective figure named Sherlock Holmes with his companion, Dr. John Watson. And he wrote a novel, we would call it a novella today, called A Study in Scarlet.

[00:12:56] Leslie: He had a great deal of difficulty selling this. It was eventually sold to Samuel Beaton, the publisher whose wife, Mrs. Beaton, was the author of the very popular household handbook. It appeared in the Christmas Annual in 1887. Conan Doyle, unfortunately, only got 25 pounds for the worldwide rights to the story.

[00:13:20] Leslie: But he moved on to other projects. A few years later, he was approached by an editor of an American magazine Lippincott’s. J. B. Stoddard approached him and another young writer named Oscar Wilde and asked them both to write something for Lippincott’s.

[00:13:37] Leslie: Wilde wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray. Doyle wrote another novella called The Sign of the Four and decided to again use Sherlock Holmes as a character, notwithstanding the sort of lukewarm critical reception of a Study in Scarlet. Sign of the Four did better it was well received, and somewhere along the way, we’re not quite [00:14:00] sure who, whether it was his agent or it was Conan Doyle himself, he decided to write short stories.

[00:14:06] Leslie: And the short stories were submitted to a man named Greenhough Smith at a new magazine called The Strand Magazine that was being published by George Newnes. The Strand was going to imitate the American magazines and be heavily illustrated. He wanted a picture on every page. Ultimately, it was a picture every other page, but he wanted heavily illustrated material.

[00:14:30] Leslie: Doyle submitted three stories, they were accepted, and this quickly became a series later collected in book form known as The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. They began to appear in 1891. They were, to put it mildly, hugely successful, hugely successful. So successful that the Strand Magazine itself became a great success and he sold, as I said, it turned into a series of 12 stories, and when that was finished, the Strand commissioned another series of 12 stories, later published as the Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes.

[00:15:06] Leslie: By the time the second series was finished, Doyle was really quite tired of Sherlock Holmes. He thought that it kept him from doing his better work, which he conceived to be historical fiction. So, he put aside Holmes, and for the next eight years, worked on other projects novels that are, I must say, very little read today. But in 1901, he had an idea for a sort of a ghost story. And he was thinking about the central figure. He contacted — the Strand had already commissioned him to do this, they were quite eager to buy the story no matter what it was about — but he contacted his editor and said if I put Sherlock Holmes in it, will you pay me more? And NAME said yes and so that became [00:16:00] the novel called The Hound of the Baskervilles featuring Sherlock Holmes

[00:16:13] Leslie: . But careful readers noted that this took place before the last of the stories in the memoirs. In the last of the series that ended in 1893, Sherlock Holmes had died at the hands of Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls. This was not Holmes coming back from the dead, this was a reminiscence of Holmes. But in 1903, Collier’s Magazine, the American magazine, approached Conan Doyle with a very generous offer and said if he would write more Sherlock Holmes stories they would pay him extremely well.

[00:16:42] Leslie: He agreed, and this became a collection eventually called, amazingly, The Return of Sherlock Holmes, in which Holmes comes back from the Reichenbach Falls, revealing that he never died there, he just went into hiding for a few years. So, between 1903 and 1927, Conan Doyle produced another two dozen or so stories, some short stories.

[00:17:08] Leslie: He also produced another novel called The Valley of Fear another Sherlock Holmes novel called The Valley of Fear and in 1927, we have the last of the Sherlock Holmes stories appearing in The Strand Magazine. Eventually, there were four novels and five collections of short stories. Conan Doyle wrote a great deal of other material.

[00:17:28] Leslie: He’s well known for having written The Lost World, starring Professor Challenger which became the basis, eventually, for the Jurassic Park films, itself being a great movie. He also created another great character named Brigadier Gerard, who was a figure of some comedy, a soldier in the Napoleonic Wars.

[00:17:48] Leslie: He lived a very rich life. He was a sportsman. He married twice. His first wife died, sadly, of tuberculosis. He remarried shortly after that death. He had a number of children and grandchildren. He was deeply involved in the Spiritualist movement and ultimately became sort of the international spokesperson for Spiritualism.

[00:18:10] Leslie: Devoted a lot of his own money to the cause and traveled around the world talking about Spiritualism. Audiences, of course, generally wanted to talk about Sherlock Holmes, but he wanted to talk about Spiritualism. Died in 1930. And just a true gentleman storyteller, patriot, great Briton who supported his nation through its wars. He didn’t actually serve in the military, but he volunteered as a surgeon during the World War. He was a war correspondent during World War I. He wrote books about the war at the behest of the government and eventually was knighted for his services in the Boer War, becoming Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

[00:18:53] Charlie: That’s right. You know, it’s easy to forget that he was when you said that about volunteer as a doctor, it’s easy to forget that on top of everything else, he had gone to medical school as well. What a story.

[00:19:02] Leslie: Yes, although he would — it was with some joy that he gave up the practice. He had spent a year in Switzerland studying ophthalmology and came back and tried to make a success of a practice in London. The patients were thin on the ground and so he continued to write. When he sold I think he, I don’t remember which story it was, but he basically chucked it all, he reportedly uh, jumped up and joy and threw his ink bottle at the wall and said, that’s it.

[00:19:32] Leslie: I’m done practicing medicine like that. And but he wasn’t quite done with the practice of medicine, but he was done with trying to make a living as a doctor and switched over to being a writer. And he was one of the highest paid writers in England. He and Kipling were really sort of the top of the terms of compensation.

[00:19:52] Charlie: Right, right. Where was the detective story, he said, he noted, until Poe breathed the breath of life into it. Conan [00:20:00] Doyle credited the early 19th century American writer and poet Edgar Allan Poe and his fictional detective, C. Auguste Dupin — am I pronouncing that right? I’m probably pronouncing it wrong.

Leslie: Dupin.

[00:20:10] Charlie: Dupin, with creating the genre. Can you discuss what teachers and students should remember about Poe’s influence on Conan Doyle and crime stories?

[00:20:21] Leslie: Poe’s model was an important one. There were others, and I think Poe gets too much credit for this. First of all, there were detective stories before Poe, but certainly Conan Doyle knew Poe’s work, and he makes fun of it. He makes fun of, not only Poe, though, he makes fun of Emile Gaboriau, was a very popular French mystery writer who created a character named Monsieur Lecoq, L E C O Q. And he has Holmes himself make disparaging remarks about Dupin and Lecoq. Now later, Doyle said, look, the puppet is not the master.

[00:21:00] Leslie: I think highly of their work, but I put the word in Holmes’ mouth that he thought they were miserable fools, incompetent bunglers, et cetera. But in fact, there was a lot going on in the mystery field besides Poe. There was a whole sweep of stories known as the Mysteries of Cities. Stories that were being published widely in the middle of the 19th century that certainly Conan Doyle knew. In the 1860s, something seems to be in air because there are three great mystery novels that appeared. The Notting Hill Murder [Mystery] was in England, The Trail of the Serpent by Mary Elizabeth Braddon came out. And The Dead Letter in America, all of which were very successful mystery novels featuring detectives of some sort or another.

[00:21:47] Leslie: So, I mean, Conan Doyle absorbed all of that in deciding to try his hand at crime fiction. It certainly wasn’t the case that it was only Poe was, it was an influence.

[00:21:58] Charlie: Right, OK. So, I love this quote. All emotions were apparent to his cold, precise, but admirably balanced mind is how the highly analytical consulting detective Sherlock Holmes is described. He was the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has seen. Would you profile and talk about Holmes as a literary character and discuss the relationship between Holmes and Dr. James Watson, his friend, colleague, and narrator?

[00:22:25] Leslie: Well, it’s funny that you call him James Watson, as his name in most of the stories, almost all of the stories, is in fact, John Watson, though, at one point, his wife does call him James, and this has driven scholars wild.

Charlie: Oh, yeah. I did not know that.

[00:22:39] Leslie: Yeah, why she called him James. In any event. Holmes is, I like to say, he is the attainable superhero. We all would like to think that if we just work hard, we could do the things he doesn’t, we, you know, we, you don’t need to be bitten by a spider or born on another planet. You just need to be really observant and learn everything. And we could both do, we could all do that. That’s all. So, Holmes is very relatable in that respect. But he is not particularly relatable as a person. He is, in a word, prickly. He is not somebody that I think you’d want to spend a lot of time with.

[00:23:27] Leslie: He could be cold and acerbic and cutting. And I actually thought that the Benedict Cumberbatch’s portrayal of Holmes in the BBC’s Sherlock did a good job of showing that young Sherlock Holmes sort of learning that he can hurt people with his powers. We see a few instances of that in the stories, but it’s critical to the stories. And the genius of Conan Doyle was introducing the character of John Watson. Watson in the very first story becomes Holmes’ flat mate. This is not unusual for the time. It shouldn’t be seen as any sort of inappropriate relationship. Watson is recently out of the British Army and is relatively impoverished, living on a wound pension, looking for a cheaper way to get by.

[00:24:16] Leslie: Holmes, at the very beginning of his career, still is struggling to make ends meet as well, and they decide to go in on rooms in Baker Street. In the beginning, Watson doesn’t really quite know what he’s in for. But he soon warms to the idea that Holmes has this exciting life, a wide range of clients and jumps into becoming his sidekick, if you will.

[00:24:42] Leslie: And we see all but. I think three of the stories are told from Watson’s perspective and that is what makes them work, frankly. John Watson is a person with whom we would like to hang out. Warm, loyal, [00:25:00] dependable, intelligent. And a friend of Sherlock Holmes. So, would I like to hang out with Holmes? Probably not, but would I like to hang out with Watson and have him tell me stories about Holmes?

[00:25:13] Charlie: It’s funny. It sounds like Watson was really more like Conan Doyle himself than Holmes was in your description

[00:25:17] Leslie:. I think that’s right. Although, although Doyle did from time to time, try his hand at detecting, sort of the combination of the two. But I think that’s absolutely right. I think that Watson and Doyle shared many characteristics, including a love of sports. And it worked well.

[00:25:37] Charlie: As the story A Scandal in Bohemia reveals even the brilliant Mr. Holmes can be outsmarted when he’s bested by the enchanting femme fatale Irene Adler. To Sherlock Holmes, she is always the woman, Watson explains, and ever after Holmes treasures her photograph. Can you tell us about Irene Adler, her relationship to Holmes, and how Conan Doyle portrays her intelligence and personality? [00:26:00]

[00:26:02] Leslie: I mean, I think I have to say that her role in the stories is exaggerated. She only appears in one story. although she is mentioned briefly in another, but Romanticists like to think that this is the love of Sherlock Holmes’ life and she may well have been, I mean, he’s not, he’s certainly very impressed with her, he keeps her photograph And he wears a guinea, a coin, that she gave him, on his watch chain afterwards to remind himself of her.

[00:26:34] Leslie: Was he reminding himself because he thought she was hot stuff? Was he reminding himself because he wanted to remind himself that there were people in the world who were just as smart as him? She doesn’t do any detecting. She tricks Holmes. She basically sees through his attempts to trick her and follows him in a disguise at one point.

[00:26:58] Leslie: And those are sort of the high points of her achievements. She is a very successful singer. She’s an opera singer and she’s had various liaisons over her life. She is part of the class of what in those days was referred to as the grand horizontals, the actresses mainly who had relationships with wealthy, powerful people, men and achieved great fame themselves, Lily Langtry probably being the leading of those, but there were many others.

[00:27:30] Leslie: there are fans of the stories that like to idolize Irene Adler. I think that’s exaggerated, but it’s fun. There are in fact series of books written about Irene Adler in which she is the featured player. Holmes is just a minor character. I think that’s a little over the top, but hey, whatever floats your boat, you know?

[00:27:51] Alisha: Love that. So, my turn to ask you a few questions. This is very intriguing for me. So arguably the [00:28:00] best known Sherlock Holmes cases are The Hound of the Baskervilles, Speckled Band, The Red Headed League, and A Scandal in Bohemia. Could you talk about a couple of these stories, what you would consider to be their most engaging features, and how more teachers and students can be drawn into enjoying them?

[00:28:18] Leslie: Well, The Speckled Band and The Red Headed League are stories that are frequently, I mean, those are the ones I probably read when I was a kid, and they entranced me, they were brilliant examples of friendship and deductions so they, combine those features. Let’s take them one at a time, so A Scandal in Bohemia, as we’ve already said, features Irene Adler, and we see Holmes making some brilliant moves, but having his moves countered by an equally intelligent woman.

[00:28:51] Leslie: Certainly an important lesson for teachers and students alike. In The Speckled Band, we have a really bizarre tale. Without giving away the secret of the story, let’s say that the murder committed in the story, which Holmes quickly deduces was murder, although it’s not clear when the case presented him, is done in a very outré manner.

[00:29:15] Leslie: And this is very much in the style of the fascination of the British public with all things Indian at the time, remember that India had been a, or was still at that time, a very important British colony. Many, many people in London had come from India, had spent time in India, had worked in India, had lived in India, may have even been born in India.

[00:29:39] Leslie: And so, it fascinated, and there’s a lot of Indian elements in the story as well as sort of a distorted view of The Raj, and perhaps what it did to people. But they’re very clever stories. They were part of the earliest story batch, they actually were part of the first six stories that appeared in the Strand Magazine and eventually collected in the Adventures. And I think, you know, many Sherlockians, many fans are very fond of those stories. Although, neither of those is my personal favorite. My personal favorite is another one of the early stories called The Blue Carbuncle, which is set the day after Christmas.

[00:30:16] Leslie: But in any event we’re talking about those. And the third I’ve already mentioned, The Hound of the Baskervilles. The Hound of the Baskervilles is very satisfying in this particular respect: It’s the longest of the Sherlock Holmes stories. And so, we get a lot more of our hero. And a lot more of Dr. Watson. In the other three novellas, there are large intermissions, intervals, if you will. In A Study in Scarlet, there’s a flashback to the Mormons.

[00:30:46] Leslie: In Sign of Four, there’s a flashback to India. And in The Valley of Fear, there’s a flashback to historical facts of the Molly Maguires in the coal mines of Pennsylvania. Those are large intervals, the number of chapters devoted to those where there’s nothing Sherlockian about them.

[00:31:05] Leslie: There are stories that took place 20, 30 years previously, and they inform the events of the current events. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, it’s all contemporary. And so we get lots of Holmes, and I think this is why it’s, always rated one of the handful of the best mystery novels of all time. It’s got brilliant deductions, it’s got scary sort of supernatural stuff going on. And a lot of fascinating characters. There’s a number of sort of red herrings in the story. So, it’s a terrific book. It’s an atmospheric book. A great one for Halloween. And so, I highly recommend it.

[00:31:44] Alisha: Definitely a lot that students and teachers can get into. I love it. So, nobody challenges Sherlock Holmes’s many talents more than his arch enemy, the mastermind of London’s underworld and Napoleon of crime, Professor James Moriarty. [00:32:00] So would you discuss Professor Moriarty, the crime stories where he’s most famously squares off against Holmes and the key dynamics of their rivalry?

[00:32:09] Leslie: Well, again, like Irene Adler, Professor Moriarty is shall I say, overrated. He only appears literally on camera in one — he never appears on camera, actually — we never have a scene where it is a current depiction of Holmes interacting with Professor Moriarty. What we get is some reports of his activities.

[00:32:35] Leslie: He features heavily in two stories called The Final Problem and The Empty House. In The Final Problem, as I’ve already mentioned, Holmes confronts Professor Moriarty, they battle at the Reichenbach Falls, and both disappear from view at the end of the story. Watson is left all alone to mourn his friend, Sherlock Holmes.

[00:32:59] Leslie: [00:33:00] Moriarty is — he hears about Moriarty from Holmes, who tells him that Moriarty is, the Napoleon of crime, the great archfiend who has organized crime throughout the country for that matter. And that is a version that we have no evidence of, other than Holmes’ word for it.

[00:33:20] Leslie: Is Holmes aggrandizing Moriarty? Well, you know, most Sherlockians take him at his word. But the story does have a lot of strange features. In The Empty House which is the first of the stories, that when it appeared in 1903, the Strand Magazine made no bones about what was happening. On the cover of the issue, it said in big letters, THE RETURN OF SHERLOCK HOLMES.

[00:33:44] Leslie: This is a story in which Holmes returns from apparently being dead and tells Watson what happened at the Reichenbach Falls, and he tells about his confrontation with Moriarty, and how he threw Moriarty into the falls, but escaped himself. Those two are the only stories in which Moriarty directly appears.

[00:34:05] Leslie: There is a third story called The Valley of Fear, in which Moriarty indirectly appears. And he is said to be behind a murder, but we never see, again, there’s no direct interaction with Moriarty, even with Holmes. And the reports of him are second, third-hand. This led some thinkers to come up with the idea that Moriarty was a fiction. Most successfully uh, Nicholas Meyer in his novel, The 7 Percent Solution, which was an enormous bestseller in 1974, and then a hugely successful film in 1976, had the notion that Moriarty was, in many respects, a figment of Holmes’ drug-addled imagination.

[00:34:52] Leslie: I think few scholars like that idea. they’d like to think that our hero, Sherlock Holmes, is probably [00:35:00] not quite that addled, but in any event, Moriarty has gone on to become sort of larger than the facts, a figure of pervasive evil in London.

[00:35:13] Alisha: Yes, I love it. So, in these tales, readers join Holmes and his deerstalker hat, Inverness cape and pipe with a magnifying glass and chemistry set in hand, observing the science of detective work and collecting building blocks of clues. So, can you talk about and you talked about a little bit already, but a little bit more about the enduring legacy of Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes, and his wide literary impact on detective crime and spy novel stories and films.

[00:35:42] Leslie: Sure. The legacy of Holmes was almost immediate. The police began to sit up and take notice of the methods that Conan Doyle was espousing. He didn’t really invent any of the techniques, but he pulled current ideas into the stories. At the time of policing in the 1890s and early1900s fingerprints, for example, were not commonly used to identify criminals. They were being used to confirm identity of a criminal, but because there was no database of fingerprints, people couldn’t get a fingerprint and then say, aha, it was Les Klinger who did that crime.

[00:36:22] Leslie: Similarly, the police were just beginning to pay attention to what later was known as the Locardian principle, the idea that criminals interacting with a crime scene would leave behind physical clues that any interaction would produce some clues of what had happened there. This was a astute observation by Conan Doyle.

[00:36:47] Leslie: He picked up the science of observation from his teacher, Dr. Joseph Bell, and applied it to Holmes. He had Holmes basically paying attention to things, whether it’s cigarette butts or blood marks or fingerprints or all those things. And this was a new approach for policing. it was adopted by the police in part because of the Sherlock Holmes stories, I think.

[00:37:13] Leslie: But also because it was becoming evident that it worked. It was certainly popularized by the Sherlock Holmes stories — the idea that detecting consisted of more than finding somebody who would rat out the criminal.

[00:37:27] Alisha: Very interesting. Thank you for that. So finally, since it’s Halloween, yay! — and your impressive published works included annotated editions of Dracula, Frankenstein, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Would you tell us why these 19th century horror stories remain so timelessly important to storytelling and popular culture around the world?

[00:37:49] Leslie: these were iconic figures. Each one of them achieved a kind of near-mythic status. this is a time, in the 19th century, when we really [00:38:00] have the reinvention of myth. We had, for hundreds and hundreds of years, lived on the basis of the Greek gods, the Roman gods, and so on, but there was — as storytelling arose in the 19th century with the advent of reading, basically, the middle class began to read, and eventually even the lower classes were able to read because of the schools, and because of the cost efficiencies of printing — there was a hunger for mythology, for new mythology. Every one of those characters, whether it’s Dr. Jekyll, Mr. Hyde, Frankenstein’s creature Dracula, or Sherlock Holmes, they were larger than life. They took on mythic status, and they each reflected universal qualities that reflected, you know, concerns of the human public.

[00:38:55] Leslie: I mean, for example, Jekyll and Hyde deals with the timeless question of how do we come to grips with who we are? And searching within oneself and recognizing the good and bad elements of ourselves and bringing them into harmony. Frankenstein dealt with the role of parenthood. It’s really not about a scary creature at all. It’s about the responsibilities of paternity. Victor Frankenstein creates a creature and then abandons it and then suffers the consequences of that abandonment as the creature is lonely and distraught and hungry for company. Sherlock Holmes embodies the age of reason and the idea, the ideal that we can deal with the problems of life if we just work hard enough to think about them, and we can overcome them with our minds. A very appealing idea to the Victorians that science could better the world. And Dracula — Dracula is very much a book about struggling with outsiders. And Dracula is, after all, an immigrant and he is a threat to London and all those people in London who are his potential victims. And so, really, these are books about mythic creatures struggling with problems that are still with us today.

[00:40:21] Alisha: Wow, you definitely helped change my thinking about some of those stories. Thank you for that. So, as we close, one of my favorite parts is to have our esteemed authors read one of your favorite paragraphs or excerpts from a book. So, would you do that for us? Read one of your favorite paragraphs from your annotated Sherlock Holmes to close us out?

[00:40:44] Leslie: Okay, so this is from the introduction in which I was struggling with how to talk about Holmes. I’ll cheat, and it’s actually a few paragraphs, but let me read, I’ll try to read it quickly.

[00:40:58] Leslie: Although the 20th century produced many firsts, the mystery or detective story was not among them. In 1901, one critic made reference to thousands of tales of detection published in the previous 50 years. Even then, however, only three detectives themselves were memorable. Edgar Allan Poe had written three stories about Monsieur Dupin, Emile Gaboriau had invented tales about Monsieur Lecoq, and Arthur Conan Doyle had brought to the public’s attention a series of adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

[00:41:29] Leslie: Today… Lecoq has effectively vanished, and while Poe’s short stories are revered as models of writing, the character of Dupin is all but forgotten. Yet a century after this observation, Sherlock Holmes is alive and well. What is it that we love or should love in Sherlock Holmes? Edgar W. Smith, then leader of the Baker Street Irregulars and editor of the Baker Street Journal, pondered this question in 1946.

[00:42:01] Leslie: Perhaps emblematic of those times, he concluded, Holmes stands before us of a symbol. Of all that we are not, but ever would be. We see him as the fine expression of our urge to trample evil, and to set aright the wrongs with which the world is plagued. He is the personification of something in us that we have lost, or never had. For it is not Sherlock Holmes who sits in Baker Street. Comfortable, competent, and self assured. It is we ourselves who are there, full of a tremendous capacity for wisdom, complacent in the presence of our humble Watson, conscious of a warm well being, and a timeless, imperishable content. That is the Sherlock Holmes we love.

[00:42:48] Leslie: The Holmes implicit and eternal in ourselves. But this answer, although psychologically insightful, is necessarily only a partial one. For the stories are not mere character studies of Holmes, but rather detective stories, set in a specific time and place, with a large cast of supporting players. That’s the beginning of my introduction to the new Annotated Sherlock Holmes.

[00:43:15] Alisha: Absolutely. Perfect. Thank you so much for joining us for reading that for answering our questions. It’s been great to have you.

[00:43:22] Leslie: Thank you. Thank you.[00:44:00]

[00:44:38] Charlie: Well, that was a great interview. We’re going to move now to the tweet of the week, from Education Week. And it says I should, well, it’s an Education Week on X, we have to stop saying tweet, I guess, but roughly eight in 10 school districts spent part of their federal COVID relief funds on after school or summer learning.

[00:44:56] Charlie: And I think that as we’re coming to the time when this federal money is going to dry up, we’re going to sort of be reading much more about where it went and, what the impact was. So that’s an interesting one to follow, I think.

[00:45:07] Alisha: Yeah. And it was the right thing to do. The question is, was it high-quality services, right? So as you said, it remains to be seen, and I’m looking forward to seeing that data when it comes out.

[00:45:19] Charlie: Absolutely. Absolutely. Well, I hope you’ll join us next week. The guest will be Dr. Carol Swain, who is a retired professor of political science and law. at Vanderbilt University. I have to give a shout out to Vanderbilt, my law school alma mater, and she’s the author and editor of eight books, including The Adversity of Diversity.

[00:45:41] Charlie: As always, Alisha, it’s been an absolute pleasure to host with you. Thank you for joining us and I hope we’ll get to do this again.

[00:45:47] Alisha: Thank you, Charlie. Me too. Always good to be with you.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Charlie Chieppo and Alisha Searcy interview Leslie Klinger, annotator of the Sherlock Holmes stories. Mr. Klinger discusses Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; the creation of the Sherlock Holmes character; Holmes’ relationships with Dr. Watson, Irene Adler, and Professor Moriarty; and famous Holmes cases. He also explores Edgar Allan Poe’s influence on the detective genre, as well as the timeless significance of 19th-century horror stories such as Dracula, Frankenstein, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in popular culture. In closing, Mr. Klinger reads a passage from his annotated Sherlock Holmes stories.

Stories of the Week: Charlie addressed an article from Illinois Policy which highlights the Chicago Teachers Union pressuring for shorter charter school contract renewals, potentially destabilizing charter schools. Alisha talks about a story from The New York Times exploring how companies in Germany and the United States are conducting civics workshops to educate employees on democratic principles, disinformation, and voting, aiming to foster healthy discourse and strengthen democracy.

Guest:

Leslie Klinger is considered one of the world’s foremost authorities on Sherlock Holmes, as well as being an attorney who specializes in tax, estate planning, and business law. He is a noted writer, literary editor, and annotator on the classic horror fiction genre and history of crime, including: the Sherlock Holmes stories; the novels Dracula, Frankenstein, and Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the stories of H.P. Lovecraft; the Edgar-winning Classic American Crime Fiction of the 1920s, as well as Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman comics and American Gods; and Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’s graphic novel Watchmen. He is currently the editor of the 16-volume Library of Congress Crime Classics series. Les attended the University of California where he received an A.B. in English and also earned his J.D. degree from the University of California School of Law.

Tweet of the Week:

https://x.com/educationweek/status/1717873821556875409?s=46&t=ABfrvSJ97fqBLKfOnxBuPw