How an Obscure Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Ruling Crippled Public Records Law

Who’s buried in Grant’s tomb? What color was Napoleon’s white horse? What constitutes a public record under Massachusetts public records law?

On the surface, all of these seem like straightforward questions with equally straightforward answers. However, anyone whose been on the receiving end of those first two gotchas – Grant and his daughters, grey – know that what sounds straightforward can be anything but.

Let’s take a closer look at the third question. Now, on the straightforward surface level, public records should constitute any records created by a Massachusetts public official while performing their public duties, right?

Well, according to Massachusetts Supreme Court, wrong. It depends a great deal which public official you’re asking, and whether or not they’re in a generous mood.

Some background: back in 1995, Ann K. Lambert – now Legislative Director for the Massachusetts ACLU – asked through a public records request for a completed copy of a questionnaire submitted to the Judicial Nominating Council by a judicial candidate. The council, which operates under the office of the Governor, refused, and two years later, the case ended up before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

Some background: back in 1995, Ann K. Lambert – now Legislative Director for the Massachusetts ACLU – asked through a public records request for a completed copy of a questionnaire submitted to the Judicial Nominating Council by a judicial candidate. The council, which operates under the office of the Governor, refused, and two years later, the case ended up before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

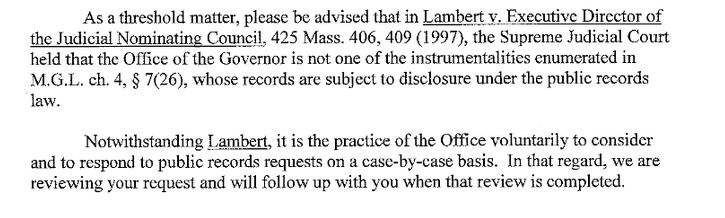

In that case, 1997’s Lambert v. Executive Director of the Judicial Nominating Council, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that, as the public records law did not expressly include the Legislature, Judiciary, or Executive branches, those branches can be considered exempt, and therefore any disclosures are liable to their discretion.

“Neither the Legislature nor the Judiciary are expressly included in [clause Twenty-sixth, the Massachusetts Public Records law statute]. We have noted that “[t]he Legislature is not one of the instrumentalities enumerated in [clause Twenty-sixth], whose records are subject to public disclosure. It is not an ‘agency, executive office, department, board, commission, bureau, division or authority’ within the meaning of [clause Twenty-sixth].”

“We also have determined that court records and “all else properly part of the court files were outside the range” of inspection based on the text of [clause Twenty-sixth]. Likewise, the Governor also is not explicitly included in clause Twenty-sixth. “Like the Legislature and the Judiciary, the Governor possesses incidental powers which he can exercise in aid of his primary responsibility.”

And with one bang of the gavel, Massachusetts public records law was lopped off at the ankles.

Agencies throughout Massachusetts saw the opportunity that the Lambert case gave them, and quickly incorporated it into their public records disclosure policy. Anybody who has filed a request with the Governor’s office within the last two decades is familiar with Lambert caveat – “We really don’t have to give this to you, but as a gesture of our largesse, we’ll consider it.” A dubious legal ruling turns your right to know into the privilege of a public official.

Other agencies are not so generous. The Judiciary branch, for example, are more than happy to pursue the full potential of immunity granted to them by Lambert, and will reject any public records request whole cloth, regardless of its content. Considered in wake of the scandals and corruption that the court system has been accused of as of late, their commitment to Lambert seems less a matter of interpreting the law as it does avoiding it.

Other agencies are not so generous. The Judiciary branch, for example, are more than happy to pursue the full potential of immunity granted to them by Lambert, and will reject any public records request whole cloth, regardless of its content. Considered in wake of the scandals and corruption that the court system has been accused of as of late, their commitment to Lambert seems less a matter of interpreting the law as it does avoiding it.

Lambert’s something of an in-joke among Massachusetts transparency advocates, and like most in-jokes, it doesn’t hold up under outside scrutiny. Transparency, once a buzz word, is now elevated in the minds of the public. It’s not a nice-to-have, it’s a must. I wonder what would happen if Lambert were to be heard today rather than almost twenty years ago. My guess is that the Supreme Judicial Court would have looked a little harder in between the lines and the public would have the access it rightfully deserves.

All we can hope for is that it’s a matter not of if a case was brought, but of when.

J. Patrick Brown is the Editor of Muckrock.com, an organization which facilitates public record requests and serves as an independent news source covering government transparency issues nationwide.