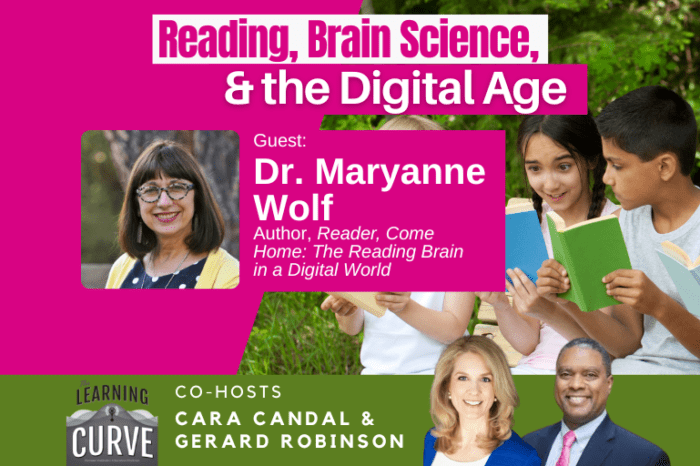

UCLA’s Dr. Maryanne Wolf on Reading, Brain Science, & the Digital Age

/in Academic Standards, Featured, Podcast /by Editorial StaffThis week on “The Learning Curve,” Cara Candal and Gerard Robinson talk with Dr. Maryanne Wolf, Director of the Center for Dyslexia and Diverse Learners at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, and the author of Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World. They discuss American K-12 education’s approach to reading instruction, and how we can increase students’ enjoyment of reading for its own sake, as well as their performance on national assessments. She reviews the findings from her 2007 book, Proust and the Squid, on how reading shapes and transforms our knowledge and emotions. They delve into how technology is changing our attention spans and ability to digest and understand more demanding books and ideas, and the negative impact of smart phones, screens, and multi-media on the brains of young people. She differentiates between acquiring knowledge through the printed or written word and digitally, and how educators and parents should think carefully and constructively about the use of technology in schools and at home. The interview concludes with Dr. Wolf reading a favorite passage from Reader, Come Home.

Stories of the Week: How did the pandemic school shutdowns affect the seven million students in America who did not receive special education services – and what can we do about it? Schoolchildren in Florida are suffering from learning loss as a result of school closures in the wake of the tragic, category-four Hurricane Ian. Can we better prepare for school shutdowns after natural disasters?

Guest:

Dr. Maryanne Wolf is a scholar, a teacher, and an advocate for children and literacy around the world. She is the Director of the newly created Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. Previously she was the John DiBiaggio Professor of Citizenship and Public Service and Director of the Center for Reading and Language Research in the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development at Tufts University. She is the author of Dyslexia, Fluency, and the Brain (2001), Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain (2007), Tales of Literacy for the 21st Century (2016), and Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World (2018).

Dr. Maryanne Wolf is a scholar, a teacher, and an advocate for children and literacy around the world. She is the Director of the newly created Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. Previously she was the John DiBiaggio Professor of Citizenship and Public Service and Director of the Center for Reading and Language Research in the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development at Tufts University. She is the author of Dyslexia, Fluency, and the Brain (2001), Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain (2007), Tales of Literacy for the 21st Century (2016), and Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World (2018).

The next episode will air on Weds., October 26th, with Miranda Seymour, a novelist and biographer of Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein.

Tweet of the Week:

ACT Scores: “The national average Composite score for the graduating class of 2022 is 19.8, down from 20.3 for the graduating class of 2021, the lowest average score since 1991.” https://t.co/0pL53eM5aZ

— Education Next (@EducationNext) October 17, 2022

News Links:

Pandemic shut down many special education services – how parents can help their kids catch up

Mitchell Yell, University of South Carolina

Extreme weather has devastated schools around the country. Now their students are suffering https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/17/us/extreme-weather-schools-hurricane-ian-climate/index.html

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a Transcript of This Episode

Please excuse typos.

[00:00:00] Cara: And we’re back. It’s another edition of The Learning Curve, the Fall edition. This is Cara Candal here with my favorite guy, Gerard Robinson. Don’t tell my husband. You know, my favorite co-host guy Gerard Robinson. And Gerard, I gotta tell you, I was walking home from taking my kids to school the other morning and looking at the beautiful fall leaves, and I thought to Ms.

[00:00:45] Oh, lime green. I see what he’s saying. Not something my eyes had ever translated before, Gerard. But I’m feeling you, I get it. And I wanted to acknowledge that I saw here the same [00:01:00] thing you are seeing in Virginia. How you doing

[00:01:02] Maryanne Wolf: that is?

[00:01:03] GR: That is great. I’m doing well. I’m actually speaking to you today from a parked car waiting to get my middle daughter, but I see lime green, and I also must say that I’m across the street from a Mexican restaurant, and when I think of lime green or lime, I’m also thinking about Margarita.

[00:01:20] I, Yeah. Yeah.

[00:01:23] Cara: Hard to have a margarita when you’re waiting to pick your daughter up from school though, it’s not a good look. So it’s a good thing you’re staying.

[00:01:28] Maryanne Wolf: Exactly, yeah. We’re we’re happy about that jar , but boys prior. Yeah, right. It’s the perfect

[00:01:35] Cara: time of year. It’s getting colder out there, at least here.

[00:01:38] And, you know, listeners, I just want this to be an example of the fact that we are so dedicated that we. From anywhere. Gerard and Cara, we’ve worked from anywhere. And Gerard, I have to sympathize with you because I think by my count this past weekend between three kids, I attended six games. Attended a fundraiser and had a house guest.

[00:01:59] [00:02:00] So like working parents, I don’t how they do it. I know, and I spend even with said house guest and attending fundraiser, I spend most of my time in the car just shuttling people, places. The things we swear we will never do, but we all do

[00:02:13] Maryanne Wolf: when it

[00:02:13] Cara: comes to. The children. Jerard, I wanna cut to my story of the week, which as so many of our stories are, is about the children.

[00:02:22] And a couple weeks ago we had a story of the week, in fact I did. That was about the individuals with Disabilities Education Act and sort of the genesis of access for all in this country. And in talking about the history of that, one of the things we didn’t. Was how students with special educational needs, students with disabilities, students with other needs, students who are on what we call 5 0 4 plans, which, sometimes it means students require a little bit of extra support in the classroom of, various kinds.

[00:02:52] We didn’t talk about. How tough it was for. So it was tough for all kids during the pandemic and times of remote learning, [00:03:00] but especially for the roughly 7 million students in this country, who, according to the article, I would like to discuss. Didn’t get the Special education services to which they were entitled under Federal Law during the Pandemic.

[00:03:17] So I’m looking at an article here from the conversation entitled, Pandemic Shutdown, Many Special Education Services, How Parents Can Help Their Kids. Catch up and this is by Professor Mitchell yell. He is a professor of educational studies at the University of South Carolina. And this story really made me think about a phone call I got about a year ago from a friend who after schools were shut down for so long in our community for two and a half years, almost in some cases her daughter had gone back to school and for a full, like two months of the school year her mom had been asking, Why isn’t she getting the special educational services that she was getting before the pandemic? She, justified.

[00:03:55] That her daughter wasn’t getting what she needed during remote learning, and now she was ready to have those [00:04:00] services back and they weren’t there. And quite frankly the school was so overwhelmed was their answer that this had quote unquote fallen through the cracks. And of course they were very apologetic and my friend loves her daughter’s school and all of the things, but this was very, very upsetting.

[00:04:14] And the one thing that I remembered I am not an expert in special education, but I do have a doctorate in education, and the one thing I remembered to tell her was, you are entitled to compensatory education services under federal law. And so what does that mean? It basically means that she was entitled to extra services to make up for the period of time in which her daughter was not receiving the services that were agreed.

[00:04:41] Between school and parent, the legally binding agreement that is the individualized education plan or the I e P. And so this article was written to remind us that there are, as I said, roughly 7 million students in special education who did not get their I E P [00:05:00] or 5 0 4 service. During the pandemic, and this is according to parent surveys.

[00:05:05] And so what this author is trying to, get the word out he’s trying to do is let parents know about these compensatory education services. Let parents know that they’re in fact entitled to this under law. we had talked about how it’s legally binding a couple episodes ago when folks have an iep.

[00:05:22] And I think that this is just a really, really important thing to bring. But what it also brings to mind, Gerard, and I know that this is a topic near and dear to your heart, is that our special education system is very good for some children, and really a lot of districts do a wonderful job. A lot of teachers do a wonderful job, but it can also be incredibly complex.

[00:05:42] For parents to navigate very confusing and lengthy process. And too often in this country, parents don’t have advocates to walk them through that process. They’re very lucky when teachers and schools act as those advocates. But of course that can’t be the case in every single case. I [00:06:00] wanted to bring to light another.

[00:06:02] Happening right now in the state of Texas, which I think is just amazing. It was born of the Pandemic and now it is in law in Texas, and that is called the Texas Supplemental Special Educational Services Program. It is run out of the Texas Department of Education and it gives students with an I E P.

[00:06:21] It was started during the pandemic with years funding with federal funds. It gives students with an IEP a one time $2,500 award, and the parents can use that money to direct towards a really wide variety of approved special educational services that the state will then pay for. So special educational.

[00:06:40] Therapies, et cetera, et cetera. This program has been so wildly popular with parents, many of whom have children with severe disabilities. That meant they were unable to participate in remote learning. This has been so wildly popular with parents that it has quite an extensive wait list. The Texas legislature has in fact [00:07:00] appropriated money to this program, and I think as they go back into session this year, because as you know, Texas isn’t always in session that they’ll be looking to appropriate more to accommodate children on the wait list.

[00:07:11] So yes, parents, we should be asking for compensatory educational services. We should be trying to do whatever we can to navigate this incredibly complex system. But there are other other solutions out there as well that states can consider. And I hope that the learning curve is a place where as people listen, we can bring those kinds of programs and options in really cool innovation.

[00:07:33] To light. So, Gerard, as I said, I know that you are a member of a board that thinks a lot about kids with different abilities. I’d love to know your reaction to this article.

[00:07:43] GR: First one is a question. It sounds like the Texas program is similar to a special needs tax credit or possibly a let me, a different version of ESAs.

[00:07:56] Am I hearing that?

[00:07:57] Maryanne Wolf: You

[00:07:58] Cara: are, I like to call it a micro grant [00:08:00] because Okay. Um, Many ESAs require kids to leave the public system, and this one is for kids in the public system. Got it. So kids with IEPs in the public system, that’s a differentiator. But yeah, you’re right. It’s flexible spending very parent and kid centered much like an asa.

[00:08:15] GR: My first introduction to the complexity of special ed at a school district level was in the late 1990s when I worked for DC Public Schools. Arlene Ackerman at that time, Superintendent Dr. Arlene Ackerman. We found ourselves often in and outta court because we were under a consent decree. I think it was the Blackman decree dealing with special ed.

[00:08:37] And there were a lot of things we did right and a lot of things we did wrong. And one thing I learned from one of the attorneys who would sue us with regularity is he said, We all. Want to help children, but the bureaucracy of delivery is just not that easy. Yes, we sue because we wanna represent our clients, but trust me, we would rather use our time and use your resources to better serve kits [00:09:00] that was in the nineties.

[00:09:01] Fast forward to 2022. I’m glad to see Texas taking a, a entrepreneurial approach to doing this work. But it just shows the complexity of the program, or I would say of special ed in general. But I’d also like to say that there’s been a strong role of philanthropy. In trying to get parents involved.

[00:09:17] So another example is when I was president of the Black Alliance for Educational Options, we were fortunate to receive a grant from the Open Society. more particularly, it was under the work of Sean Dove, who had an initiative focused on black men. And we received a grant to work with ultimately 2000 black parents in nine cities who had a black boy youth or teen in special.

[00:09:43] And there’s surely some students who should be in special ed, but a lot of times we know that black boys in particular don’t wanna overlook black girls cuz there’s a rise in that too. And we see that with the school to prison pipeline are often referred to special education, not for education or academic reasons, but Due to [00:10:00] behavioral challenges or something else. And so we put together a program called Parents with Power Program to get parents more engaged, more involved and really to have an idea of what it took to really be an advocate for your own child. So there’s a state role, there’s a philanthropic role, there’s a local role, but I’m glad to see Texas doing some great things and to all the families who have a student with the special needs.

[00:10:24] Keep up the good work. I mean, I know it’s tough and we have a range of different type of disabilities and maybe that’s not even the best term the more that I begin to think about it. But just keep up the good work because there are a lot of hardworking educators, superintendents, principals and attorneys who are working to make it happen.

[00:10:42] It’s not gonna change overnight. We know that for a fact. But glad to see when a department of. It’s a big win. So congratulations. my story is also about weather, but it’s not the great. Where the conversation we have at the beginning of our show. So this is from Renee Marsh at cnn. The [00:11:00] title is Extreme Weather As Devastated Schools Across the Country.

[00:11:04] Now students are suffering. So before I began my condolences to families in Florida and into the southeastern. Part of the United States who lost loved ones friends, children, and others to the recent hurricane. And this story in part is about Florida because as many of our listeners know, Hurricane Ian was a category four storm that slammed into the state and just reed hav it across the board.

[00:11:29] Well, we often know about the businesses that are closed. We know about homes that. Stated, but we often forget about the schools. And schools were the ones that had children between, let’s say, eight 30, sometimes to five o’clock each day. Well, when schools are. Where do they go? So the article really did two things.

[00:11:48] One, it just wanted us to realize that when we think about hurricanes, we’ve gotta figure out what to do for schools. Some schools, in fact, reopen and students are back in the classroom. Teachers are [00:12:00] back in the classroom. But there are hundreds of schools that. Did not. And in one example that Renee identified even a previous storm in Louisiana, there’s still a couple of schools today that haven’t opened as a result of that.

[00:12:12] So when we think about storms and hurricanes, we’ve gotta figure out what to do. Number two, she also wanted to put in play that Hurricane Ian is. Natural disaster, but there’s several others taking place across the country that we should keep in mind. Number one, for example, in California, my former home state between 2018 and 19 alone, there are more than 2,200 closures of schools due to wildfires.

[00:12:39] And currently in California there are wildfires. They’re leading to closures of schools in that state. We know that. In January, there was a study published by the federal government accountability office, which looked at the number of presidential declared disasters. Since [00:13:00] 2017 across the United States, there were over 300 and schools were heavily impacted, even in Tennessee.

[00:13:07] Given the rainfall schools had to close. We as the public should try to figure out what we can do to help our schools. And one thing we can do is to educate ourselves about what services are provided from. For example, the State Department of Education or a sister agency. So at your Department of Education, you should go to your web page type in emergency preparedness and identify.

[00:13:32] Services your Department of Education will make available to you as an individual to your school or to your system in case of an emergency on some Department of Education home pages for the state. They’ll have links to your school district or school divisions. We have here in the Commonwealth and you can identify what services the school board Super.

[00:13:54] And then, or the system through partnership with other agencies can provide. So that’s one source to look at. [00:14:00] Number two is to take a look and see whether or not your university public or private in your city has an emergency preparedness program. So for those of you who have a pen and paper or a pen and pad or wanna type, write down this name.

[00:14:16] His name is Dr. Kevin Ku competes. His last name is spelled k u p. I E T Z. He is the chair of the Department of Aviation and Emergency Management at Elizabeth City State University in North Carolina. He is a certified firefighter and paramedic and has over 20 years of service in emergency management and responses, not only in the United States but outside as well.

[00:14:41] A few years ago Kevin provided. A PowerPoint presentation about emergency preparedness and emergency management, and the group of people I invited were scholars. They were non-profit directors, they were employers and all of us. Just when Kevin completed this presentation [00:15:00] were just shocked.

[00:15:01] A, because we realized how much we were unprepared for an emergency at our. In our place of business and our school. And so Kevin has a course. He also provides training to state and local leaders. So he’s someone that I would take a look at because he just knows this from the ground up. The last thing I’ll leave you with, Is the fact that we should also take a look and identify what your fire department and your police department offer in terms of locally emergency preparedness.

[00:15:33] So just something for us to think about in always provides an opportunity for us to talk about emergencies, but I gotta tell you, I’m just not sure how prepared we are as a family at home, as well as educators at schools. What is. I

[00:15:48] Maryanne Wolf: couldn’t

[00:15:49] Cara: agree more. I mean, I think the thing is, is that throughout the pandemic, many of us in in the education policy sector have been thinking a lot about how schools could pivot to remote learning.

[00:15:58] And we did it in the pandemic, which means we [00:16:00] could do it, when a hurricane comes or another natural disaster. Well, you don’t always think about all of the infrastructure that is destroyed as has happened in Florida and many other places recently. And that this is something that’s going to keep happening.

[00:16:12] Unfortunately, we. Something always has happened too. We, we’ve learned to respond differently and it’s, the information we have is much more immediate. The one thing I worry about a little bit with preparedness, worry is the wrong word I think about, is the extent to which we have to prepare children without.

[00:16:28] Scaring the daylights out of children . And I think right now a lot of adults are scared about many of the challenges we face, whether it’s a natural disaster or the potential for violence at school, et cetera. And so just striking the right balance is something that I think I wish I had more information about personally, Gerard, but all really , , great things for us to think about.

[00:16:49] So thank you for that.

[00:16:51] GR: Let me follow up real quickly on something you said about the children because Kevin and a few other people provided a similar answer. So when [00:17:00] firefighters go into a house, sometimes when the fire is over and people are dead, some of them are children, and he said, You wanna know why?

[00:17:07] I said, Why? He said, Because when the children see us in a mask in a big suit, we look like a. To them, and so they go into fear. Here comes a monster and so friends of mine who are firefighters will go to a school with the uniform on and walk through the process just to get the students aware that if you see someone like me during a fire, I’m there to help.

[00:17:32] So just something small as that. That’s

[00:17:34] Maryanne Wolf: really,

[00:17:35] Cara: I have to give a shout out to the Brookline, Massachusetts Fire Department, where I have a wonderful memory of walking by with my toddler son at the time. They weren’t attending to an emergency at the moment and they invited us in because he was so fascinated by the truck, not only to look at the truck, but to look at the gear.

[00:17:49] So, point well taken and cheers. Cheers to those who put themselves in harm’s way every single day. Okay, Gerard, Well, we’ve got an amazing guest waiting in the wings. I mean, what have we not had an [00:18:00] amazing guest waiting in the wings. This one is on a topic I’m pretty excited about. We are gonna be talking about.

[00:18:05] The science of reading and dyslexia and what we know about brain science with Dr. Marianne Wolf. She is from the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. I will read her many qualifications coming up right after this. Very excited for this conversation. We’re gonna be

[00:18:23] Maryanne Wolf: right back.[00:19:00]

[00:19:13] Cara: Learning Curve listeners, we are here with Dr. Marianne Wolfe. She is a scholar, a teacher, and an advocate for children and literacy around the world. She is director of the newly created Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners in Social Justice at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies.

[00:19:31] Previously, she was the John d Diagio, professor of citizenship and public. And director of the Center for Reading and Language Research in the Elliot Pearson Department of Child Study in Human Development at Tufts University right down the road. She is the author of Dyslexia Fluency in the Brain. Prust In The Squid, the Story of the Sciences of Reading Brain.

[00:19:52] Tales of literacy for the 21st century and reader come home, the reading brain in a digital world. I wanna explore what’s [00:20:00] behind all of those titles. We also have to say though that her most recent achievement after Maryanne Wolfe is now a permanent member of the Pontifical Academy of Science. Welcome to the Learning Curve.

[00:20:12] Congratulations, Dr. Marianne Wolf. We’re so happy

[00:20:14] Maryanne Wolf: to have. Thank you. It’s my pleasure. Here I am in LA and wishing I were seeing the foliage in Boston, . Yeah,

[00:20:24] Cara: well it’s pretty great. I’m not gonna lie, ,

[00:20:27] Maryanne Wolf: so I know that’s one of the many things I miss. In Cambridge, in Boston, New England. I’m

[00:20:34] Cara: sure it misses you too.

[00:20:36] I have to say Dr. Wolf when I’m not co-hosting the Learning Curve podcast and doing wonderful things with Pioneer Institute, I am also a policy managing director at Excel and Ed, where we think. About the science of reading and your work. And I was having conversation with my colleague, Dr.

[00:20:52] Camana Burke this morning, and she said she’s very excited that you were going to be on the show today. So we wanna dive [00:21:00] right in. So, as I noted I three titles, right? The Story and Science of the Reading, Brain and Reader come home. Great title by the way. You know, you’ve written a variety of books.

[00:21:10] You’re widely respected and. Take reading research in brain science and you make it accessible and you help us understand why these things matter. So before we get into why these things matter, how did you come to this topic?

[00:21:31] Maryanne Wolf: a, it’s such a, a wonderful question. I could spend the whole half hour with you on what really happened, and it is a story but I’ll make it very short. I always thought that I would complete a PhD in comparative literature and teach poetry and the, especially the poetry of Ryan Murphy Rka, and that was my.

[00:21:56] And I also was going to add, of course, English literature. [00:22:00] But after a master’s in all of these topics, I felt I needed one year, like a peace course experience in order to give back all that I had been given. And I certainly felt such richness my educational formation. And so I wanted to be a teacher for those who most needed it at that point in time.

[00:22:24] it was the case that I would be sent to a Native American reservation in the Dakotas where they had lost a school so that I was ready to go and almost the day before I was told we weren’t able to go there. I was to be sent to rural. Hawaii . Well, all the political goals I had went out the window. I didn’t even wanna tell people where I was going, , but the reality hit me in the face.

[00:22:55] When I was there, the families were basically indentured servants [00:23:00] to plantations sugar and pineapple and the children. Their school was, falling apart. And it was a 24 hour job really. It just taught me what poverty does in the education of our youth, our children, and what happens if you are non-literate that.

[00:23:21] Was the game changer in my life. I dropped all my plans to be in literature for the rest of my life, but rather to understand what it would take to make every child literate that I could possibly affect. And so I went to basically, The Harvard Reading Lab where I worked with Gene Cha and I worked with neurologist like Martha DLA and Norman Geron and in linguists like Carol Chomsky and Nom.

[00:23:52] But it was the combination of all these areas that taught me my way. To help children become literate [00:24:00] was to understand how the brain ever learned to read, and that knowledge, which is continuing to this day propelled me into cogni, what is called now cognitive neuroscience in which we study how the brain learns to read what happens and why when it doesn’t learn to read easily across writing systems.

[00:24:23] and I literally, yesterday I was talking with a Chinese scholar. What is the difference in dyslexia there versus English? So we are truly trying to take knowledge around the world in various ways to help as many children and as many teachers understand what it takes to be in my terms, to have the basic human right of literacy and.

[00:24:50] Literally, and in every single sense of the word dictated the rest of my life.

[00:24:56] Cara: That’s amazing. I think so often we talk about the basic human right to an [00:25:00] education, but defining that even further in saying to literacy, because not all people who are educated in this country and others become literate.

[00:25:07] I’m fascinated by your backstory. any person who’s. Watched a child learn to read. the process is so difficult to comprehend how humans can go from making noise to getting there. And so I’d love to know more about that, but I wanna pick up on, you know, so you said that Jeanie Shaw was one of your mentors.

[00:25:26] this research has gone back a, a long time, yet there is still substantial controversy and disagreement in. About how to teach reading, and it’s confounding to me, quite frankly. Mm-hmm. . But here we are in a place and you know, we’re going to receive Nate’s course soon.

[00:25:42] And, Nate’s course haven’t been great anyway in the since, since Nate was instituted in the late seventies Right. and we can predict that they’re going to really have gone down quite a bit. So talk about how it is we teach reading. I mean that probably, there probably depends on where you live, how we [00:26:00] teach reading.

[00:26:00] Right. And what are the strengths and weaknesses? What should parents in particular know about what it takes to really teach a

[00:26:07] Maryanne Wolf: child to read well? Right. And I’m so glad that you actually. Almost leading the program with this because this has been an unnecessary What Jean Shaw called The Great Debate was an unnecessary debate.

[00:26:23] If we look at what the reading brain does, when it first learns, when you under. Stand that no human being was meant to read. Genetically unlike, vision or language, you understand that the reading brain has to be taught. It is a circuit that forms just like an electrical circuit. It has to make all these connections.

[00:26:52] Well, teachers Follow their educational programs, and there’s a matter of loyalty where you are taught and [00:27:00] by whom has so often been the reason why certain methods were used. Now, there was a great deal while Gene Chaw was, alive a great deal of debate, but the unfortunate part is that all her research, all the research.

[00:27:17] 40, actually even almost 50 years, shows us that we need foundational skills to be taught in that circuit for many children and that that’s the best way of teaching. Now, the science of reading, which is something that I’m known for, if you will, or the neuroscience of Reading, teaches us that it’s not reducible just to thinking about.

[00:27:45] Foundation as phonics, though that is pivotal. It has to be there, but. Equally important is knowledge about words. And so teachers who do phonics sometimes neglect [00:28:00] vocabulary, grammar, understanding how the words work with their units of meaning calls called morphines. So there’s been this. Necessary emphasis on the sounds and the letter sound correspondence rules, which are part of phonics and decoding.

[00:28:19] But there’s been a neglect of understanding that foundational skills are multiple, they aren’t reducible in science. Only to fund and decoding, but they must also be the underlying processes that help a child move into fluency, which is what the NA scores show us. They are not fluent. They are not proficient by fourth grade, much less eighth grade, sixth.

[00:28:49] And then there are inequities that are propelling the preponder. of, decreasing scores. Covid is doing the same thing. [00:29:00] But the reality is, and this is so important for teachers and parents to know, we need to be explicit and systematic about all the aspects of word knowledge and decoding knowledge.

[00:29:15] And that is, it’s not that I’m trying to. Epox on both houses? Not at all. If, if you could see my elbows, I would have them cross so that you see in the beginning the majority of emphasis are on letter sound correspondence rules on decoding and phonics methods are so important for that. But, at the expense of neglecting.

[00:29:41] What is vocabulary? What is grammar? How words are used in sentences, What are morph themes? What are all the ways that we begin to comprehend connected texts? So that emphasis is always there. It’s, it increases over time. Just as those [00:30:00] emphasis on foundational skills as you become fluent gets to decrease.

[00:30:04] It’s never. But it, decreases as the other increases. So what our unfortunate. Unfortunate debate is that people were divided when they should have been united. But that takes a real understanding of, on both parts, how an expanded version of foundational skills actually bridges the reading wars or the reading debate.

[00:30:34] And it also bridges another debate that’s going on, Kara, that is equally unfortunate, and that is to think that if you. Dealing with science, you aren’t being culturally responsive, especially to the needs of bilingual, multilingual readers. So we really have, I think, the most beautiful way of bridging if people understand how the reading brain [00:31:00] circuit first develops and elaborate over time into deep reading, inference background knowledge.

[00:31:08] Empathy, and very importantly, especially in these days, critical analysis. I wanna

[00:31:15] Cara: ask you as somebody who thinks a lot about policies, because so much of what kids experience in school has to do with the policies that states have in place for how things should be taught, or how things should not be taught, et cetera.

[00:31:29] So Right. and I know you’ve written a book called PRUs and the Squid, The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. Yeah. How is it that you help policy makers, probably with lessons from that book, understand what it is they need to do and what exactly is it that policy makers do need to do so that

[00:31:49] Maryanne Wolf: children have.

[00:31:50] Yeah, this is really important and I’m part of a collaborative between the California State University system and U [00:32:00] University of California. I’m in UCLA, obviously, and what we are doing is working together with the state legislature to change teacher credentialing. Now, this is so important for policy, that policy about.

[00:32:19] Teachers sh. It’s not just how should they teach, but what should they know so that they can teach better? and more, if you will, neurodiverse readers like children with dyslexia. So this body of knowledge, this expanded version of foundational skills has to be part of teacher credentialing. So we are working in my group in the Center for Dyslexia and my colleagues in the collaborative, we are working really fiercely at the state level to make sure.

[00:32:56] Those teacher credentialing standards are [00:33:00] then incorporated in pre-service. Teacher of Ed, teacher of education programs. So policy is essential to change and it’s not about saying, you must use this method, or you must not use that. Rather, you must use approaches that are based on evidence and based on the science as we know it and as it evolves.

[00:33:30] So in that way, we really, I think, don’t make people who are, let’s say, in balanced literacy or whole language on the defensive, rather, we. You have a beautiful knowledge base that needs to be expanded and made explicit. And it says also to those who have been doing the very hard work of rightly insisting that phonics and decoding and learning letter sound correspondence drills has to be known by these children.

[00:33:59] [00:34:00] They too have to expand their knowledge base. So my. In California, and although I hated to have to leave Boston and Tufts and my wonderful department there, I am working at the state level, at the city level with LA Unified School System and at the university level to change policies around what teachers must know in order to teach every child to become.

[00:34:32] Well,

[00:34:32] Cara: that’s excellent and that’s incredibly important work. one of the things that’s top of mind for me as a parent, and probably our listeners will think I talk about this way too much, is the digital world that we’re living in, that we’re raising kids in. And you’ve written about this and your book reader come home.

[00:34:50] can you tell us about the way technology is changing, how and what we’re learning? are we unable to handle what [00:35:00] we used to be in terms of reading literature, in terms of engaging with the world? Or is it just a different

[00:35:04] Maryanne Wolf: relationship? it’s a very complex topic and that’s why it took a long time for me to write that book reader, come home to the reading, branding digital world.

[00:35:16] I will tell you that the evidence is so fascinating because it’s not a binary question of print versus digital, and my MIT colleague, Sherry Turkel always has said this so beautifully. It’s not about what’s innovative, it’s about what innovation disrupts or diminishes. That’s the knowledge base we need to know.

[00:35:40] So what I have written is, Our knowledge base at this moment in time shows us at every developmental. Period. There are cost and there are advantages to both mediums, but in the young child we, I would really strongly recommend [00:36:00] like the pediatricians, like Barry Zuckerman in, in Boston, that we use digital devices as little as possible.

[00:36:09] And I would even say, except for, you know, FaceTime with grandparents, a very. Very little in the first two years, and then gradually, never as a punishment, but also never as a reward, but rather as one of the many parts of their life that they can have a little of. And then by five we have all kinds of evidence about the changes of attention that are going on.

[00:36:32] We have neural imaging that shows John Hutton in Cincinnati showed that if you do the same story, parent reading. Versus an audio version versus an iPad version. The language regions are most activated with the caretaker reading to the child. So the first thing I wanna say is eight to five read to your child.

[00:36:54] Now all , we don’t have enough time to look at every developmental period. [00:37:00] Katherine Steiner, Ada does some very good work on showing attention differences, especially in adolescence. My colleagues in Europe have done a huge metaanalysis of young adults, which again, the same story is read print versus digital with comprehension questions on the plot and details at the end.

[00:37:20] Unquestionably print is superior for their comprehension, a plot and detail. Now, what this is really telling us, then when we ask what the youth think they are. Here’s where we come to a device, they say, Oh, we’re better on the screen because we’re faster. Here’s where an understanding of the reading brain becomes essential.

[00:37:44] For some things, no question, the digital is better, but for things that are complex, are important, are beautiful. Those things that we want to and use, I use your word, immerse ourselves in the print. It has many [00:38:00] advantages over digital in those areas. So if there’s something super important, a contract, a book that I really want to understand or review, I make sure I, use print.

[00:38:11] But all of this is to say there are advantages and disadvantages to both, but the thing I’m most concerned, Developmentally and for adults is that we are becoming skimmers and not using the deep reading processes because we are u expending all our time. Just moving, moving, moving. To get all this information that we’re bombarded with inside our consciousness, but it does not activate then those deep reading critical.

[00:38:45] Analytic and empathic processes that take extra milliseconds when we read. So I’ve had NPR interviews, other interviews or people asking me why am I not immersed in the same way when I’m on the screen? And the reason [00:39:00] is because you are imperceptibly, not giving the time to it. You’re not giving the time to being immersed and you don’t know it.

[00:39:08] It’s imperceptible. These are milliseconds. Real worry that I have is a political worry, and that is that last. We use those critical analytic skills, the more we are vulnerable to those familiar sources of information that we just say, Oh, that sounds right. And did we believe? Mm-hmm. , we become victims of misinformation and disinformation and demagoguery around the world.

[00:39:36] this is really important to understand. The Swiss have a, a book or a magazine section that they use on my work and they say, Are we all becoming Twitter brains? Well, , without saying anything about anyone, if particular, we’ve had people. Use Twitter for policy. This takes away the entire context [00:40:00] that is necessary to understand the complexity of any human thought.

[00:40:05] And this is where I get very worried. It’s not that we can’t use deep reading digitally on the screen. Of course we can, but we have to be conscious and aware of what we’re doing and not skim and not lose either complexity or. Or empathy for alternative viewpoints. That is,

[00:40:27] Cara: Something I had not thought about truly was the lack of engagement when I’m reading online.

[00:40:35] And I have to say that I am not a person who, and I think you, you mentioned this, if it’s something that I. Need to deeply understand, be it for work or even if it’s just because I’m reading a novel for pleasure, , I, it’s always in print. Because I think that now that I’ve heard you name it, I can recognize that I am not as engaged when I am constantly looking at a screen and the political danger.

[00:40:57] Thank you for bringing that to our attention because I think that [00:41:00] that is, That is incredibly important. We have, unfortunately, Dr. Marianne Wolf, we have come to the end of our time together, but before we let you go, it would be so wonderful if you could read us a passage from one of your books and if you wanna provide some context for why you chose that passage, that would be great as well.

[00:41:18] Maryanne Wolf: Okay, well, it’s an unusual experience for me to be written by a Conne, a Kentucky minister, but he wrote and told me, he wrote a dissertation on why my book reader come home, could be of great insight for those in theology. And he said the most important paragraph for him is the one I’m gonna read to. And here it is.

[00:41:43] Oh, cool. There may well be as many reasons why we read as there are readers, but the very raising to consciousness of the question why we read has elicited some of the most thought provoking responses by some [00:42:00] of the world’s most beloved writers. I would ask you to raise it for yourself before more time passes.

[00:42:09] After I refound my own former reading self, the answer that came to me is this. I read both to find fresh reason to love this world and also to leave this world behind. To enter a space where I can glimpse what lies beyond my imagination, outside my knowledge and my experience of life. And sometimes like the poets fed Rico Garcia, Lord, where I can go very.

[00:42:44] To give me back my ancient soul of a child, . And that’s my paragraph. That’s an amazing paragraph. That’s really wonderful.

[00:42:57] Cara: Dr. Marin, well thank you so much for your [00:43:00] time today. This has been illuminating and we greatly appreciate your work and, what you’re doing to change the world for so many kids out there.

[00:43:08] Thanks so much for your time today.

[00:43:10] Maryanne Wolf: Thank you. It’s my pleasure. And hello to all my friends, . Take care now. Take care.[00:44:00]

[00:44:26] Cara: Well, here’s a depressing tweet of the week. We’ve got a tweet from education. Next. A C T scores. The national average composite score for the graduating class of 2022 is 19.8 Ouch, down from 20.3 for the graduating class of 2021. The lowest average score since 1991. I am not saying ouch to all the kids out there that got a 19.8 or got below taking the a C T.

[00:44:55] You know it’s work. You can take it again, I’m just saying that this is definitely a [00:45:00] reflection of learning loss and no doubt that, mm,

[00:45:04] Maryanne Wolf: next week or the week after.

[00:45:06] Cara: Maybe, yeah, probably the week after we will be talking about NATE scores, which are going to be released and we’ve all heard the predictions.

[00:45:13] So until then, Gerard, let’s both go find some joy . so that we can be prepared to digest what’s happened and talk about how to work our way out of it.

[00:45:25] Maryanne Wolf: Next week

[00:45:28] Cara: we are gonna be speaking with Miranda Seymour. She is the biographer of Mary Shelly. Maybe we’ll get a little bit spooky in honor of Halloween.

[00:45:37] Until then, Gerard, I’m gonna be waiting next week to hear what you’re dressing up as. So, you’re forewarned, take care of my

[00:45:43] Maryanne Wolf: friend

[00:45:45] GR: sounds.[00:46:00] [00:47:00]

Recent Episodes

Director/Actor Samuel Lee Fudge on Marcus Garvey & Pan-Africanism

Cornell’s Margaret Washington on Sojourner Truth, Abolitionism, & Women’s Rights

UK Oxford & ASU’s Sir Jonathan Bate on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet & Love

Steven Wilson on The Lost Decade: Returning to the Fight for Better Schools in America

U-Pitt.’s Marcus Rediker on Amistad Slave Rebellion & Black History Month

Notre Dame Law Assoc. Dean Nicole Stelle Garnett on Catholic Schools & School Choice

Alexandra Popoff on Vasily Grossman & Holocaust Remembrance

Stanford’s Lerone Martin on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. & the Civil Rights Movement

ExcelinEd’s Dr. Kymyona Burk on Mississippi, Early Literacy, & Reading Science

Harvard’s Leo Damrosch on Alexis de Tocqueville & Democracy in America

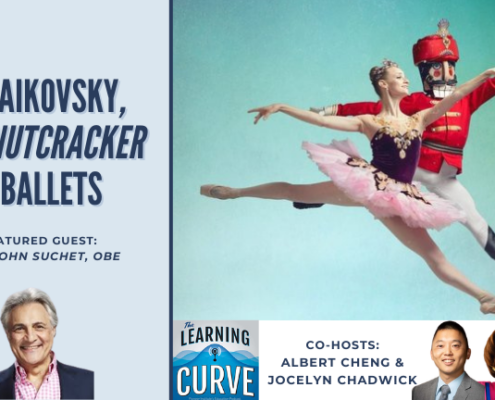

UK’s John Suchet, OBE, on Tchaikovsky, The Nutcracker, & Ballets