Marathon Endurance Test: Leaders Pave the Way for Boston’s Return

Hubwonk host Joe Selvaggi talks with Boston Athletic Association’s CEO Tom Grilk about the leadership challenges of cancelling the world’s oldest continuous marathon, a $200-million benefit to the region involving eight municipalities and 10,000 volunteers, in the face of a pandemic – and how cooperation among stakeholders brought back the epic event to be run this October.

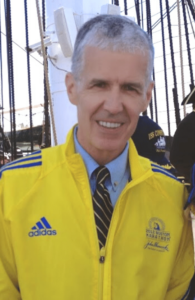

Guest:

Tom Grilk is the CEO of the Boston Athletic Association/ Boston Marathon. He has been a member of the B. A. A. since 1987, and became Executive Director in 2011 and CEO in 2016. He was President of the B. A. A. Board of Governors from 2003 until 2011. During his tenure the B. A. A. has focused its efforts in three areas: the conduct of athletic events, the operation of community service initiatives, and the training and development of athletes. Tom has had his share of hands-on experience with the Boston Marathon. He served as its finish line announcer from 1979 through 2013, and is a former competitor, having run a personal best at Boston of 2:54 in 1978. Tom resides in Lynnfield, with his wife, Nancy, and has twin sons, Christopher and David and daughter in law Stephanie. He was a corporate and business lawyer, with the firm Hale and Dorr and also served as counsel to Boston area technology companies. He graduated from Cornell University and received his JD from the University of Michigan.

Tom Grilk is the CEO of the Boston Athletic Association/ Boston Marathon. He has been a member of the B. A. A. since 1987, and became Executive Director in 2011 and CEO in 2016. He was President of the B. A. A. Board of Governors from 2003 until 2011. During his tenure the B. A. A. has focused its efforts in three areas: the conduct of athletic events, the operation of community service initiatives, and the training and development of athletes. Tom has had his share of hands-on experience with the Boston Marathon. He served as its finish line announcer from 1979 through 2013, and is a former competitor, having run a personal best at Boston of 2:54 in 1978. Tom resides in Lynnfield, with his wife, Nancy, and has twin sons, Christopher and David and daughter in law Stephanie. He was a corporate and business lawyer, with the firm Hale and Dorr and also served as counsel to Boston area technology companies. He graduated from Cornell University and received his JD from the University of Michigan.

Get new episodes of Hubwonk in your inbox!

Read a Transcript of This Episode:

Please excuse typos.

Joe Selvaggi:

This is Hubwonk. I’m your host, Joe Selvaggi.

Joe Selvaggi:

Welcome to Hubwonk, a podcast of Pioneer Institute, a think tank in Boston. For 123 consecutive years, the Boston Athletic Association, an elite running club started in 1887, has hosted the Boston Marathon, the oldest continuously held marathon in the world. This grand unbroken tradition came to an abrupt end when one month before the planned race date, the city and Commonwealth went into lockdown in response to a novel virus that was spreading across the world. Hoping to preserve the marathon, a race that brings 30,000 runners and $200 million to the Boston economy each year, race leaders in coordination with the eight municipalities along the course needed to work quickly to develop contingencies that might preserve the race while ensuring the public safety. COVID-19 had other plans and the 2020 race slipped out of reach. Now in 2021 with the dawn of safe and effective vaccines, those same intrepid leaders now prepare for the 125th running of the Boston marathon to be held on Monday, October 11th at the helm of the Boston athetic association. Through it all was its chief executive.

Joe Selvaggi:

Tom Grilk, having been the president of the board of directors from 2003 and its executive director since 2011, Mr. Grilk has led the marathon through the challenges posed by nor’easters, heat waves and terrorist attacks, but little could have prepared him for managing a major marathon in the face of a global pandemic. What was it like to guide the Boston Marathon through a public health threat that is still not completely understood. Mr. Grilk will share with us how public leaders worked together as the crisis unfolded and how he plans to hold the 125th Boston marathon this year, for the first time, in October. When I return, I’ll be joined by the Boston athletic association chief executive Tom Grilk. Hubwonk is a production of Pioneer Institute, a Boston-based think tank. It seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts and beyond. Pioneer is a 501c3 organization that relies on your support. Please visit pioneerinstitute.org to make a tax-deductible donation. Okay, we’re back. This is Hubwonk. I’m Joe Selvaggi, and I’m now joined by the Boston Athletic Association’s CEO, Tom Grilk. Welcome to Hubwonk, Tom.

Tom Grilk:

Well, Joe, thank you glad for the chance to chat.

Joe Selvaggi:

Well, this conversation is a special treat for me as a runner. There’s so much I want to talk about but I’d like to offer some background for listeners who aren’t runners. So I I’ve compared, I’ve said to them getting an opportunity to talk with you is perhaps something akin to a Catholic person getting a chance to spend time with the Pope. This is really wonderful, but let’s talk about why Boston is so special. Why is the marathon so special, why is the BAA is so special? I mean, all running clubs promote running and all marathons are 26 miles, 385 yards. So what makes the Boston marathon and the BAA so special?

Tom Grilk:

The Boston Marathon benefits, I suppose, from being the oldest, the longest contested annual marathon in the world going back to 1897, the BAA was founded in 1887. The Olympic games were revived in Athens in 1896 and the BAA sent a majority of team USA to those games along with the New York athletic club. And while they were there winning a majority of gold medals for the U S these BAA athletes they also saw the long distance run, which was about a 24 mile run, or so starting out at the Plains of marathon where the battle of marathon was fought in 490 BC. And as legend has it, Pheidippides ran back to Athens to tell the Athenians of their victory stood before them said, rejoice, we conquer, then dropped dead. So it was both a joyous and a regrettable ending to the first one.

Tom Grilk:

But the BAA athletes who were there thought that the idea of a marathon in Boston wouldn’t be an interesting idea. So the following year in 1897, the Boston marathon was conducted for the very first time starting in those days in Ashland at Metcalf’s mill, which you can still go out to and see a little monument there. And it stayed that way for a number of years until I think in the 1920s, it was moved to Hopkinton because the marathon distance was standardized at the Olympics 26.2 miles. And so we’ve had a start that goes all the way back to the beginning in Ashland, but more traditionally, and certainly for many decades as the sign out in Hopkinton says, it all starts here, the BAA has kept it going for all of those years.

Tom Grilk:

The BAA had good years early on, and then in the depression fell into bankruptcy. And there really wasn’t much left of the BA in those days, other than putting on the Boston marathon and the old BAA games, indoor games at the Boston garden which finished in about 1969 or 70. Interestingly, our current board chair, Dr. Michael O’Leary now a professor of surgery at Harvard medical school, senior urologic surgeon at the Brigham was a Harvard track athlete who ran in those final games. So there were lots of little linear connections that that run through of this as to what made Boston special history certainly did that. But as so often happens and so often in the business world, in the world of marketing, one of the things that really added to the cachet of the marathon happened almost accidentally, which is to say the advent of qualifying times for a long time, anybody could enter the marathon and come run,show up in Hopkinton, maybe have a very perfunctory physical examination made of them, including by Dr.

Tom Grilk:

His father Dr. Leary having grown up as a kid at mile seven of the race, but then it got bigger. And around 1970, the BAA board of governors was confronted with a somewhat frightening reality that there could be more than a thousand runners in the Boston marathon, what to do how do you contain the field so that it would not get out of control? And there were several choices. One would be simply first come first served. Another would be a lottery, which is a pretty common approach to solving that sort of problem. But given the BAS history as a competitive work organization that thrived on competition going all the way back to those Olympic games and before the decision was made that the field would be limited by competition. By qualifying times, one would have to beat a certain time.

Tom Grilk:

And with that over the years, that became quite a lure for people to qualify for Boston getting what is often referred to as a BQ, a Boston qualifying cut became something of a badge of honor among people. And as that happened the pressure to get in grew, the field size grew, and the qualifying times came down having gotten as low as two hours and 50 minutes for men under 40 back in the late seventies, early eighties. So w with that came a fair degree of cache not made as marketing decision, but one that could be touted that way of one had been around in 1978 on the BA board and said that was their motivation. Sure.

Joe Selvaggi:

It’s a wonderful, I appreciate the background. That’s a wonderful story with what came as a stunt after coming back from the Olympics with 15 guys out in Ashland has now become a global event. And you, I think rightly pointed out the qualifying time does make Boston unique as they say every other, a marathon is merely a qualifying race to get to Boston Right. Fair enough. But the time has come down and actually gone back up. I think now the without any age or sex handicap,uthe qualifying open time is three hours, five minutes still a pretty fast pace. UI believe,uwe’ll, we’ll give you a chance here, your own PR or BQ a was a little faster than that. Do you want to share with our listeners?

Tom Grilk:

Well, it took me several tries to get under three hours a long, long ago, and I failed on multiple occasions. I finally made it and then instantly the qualifying time was a lower two hours and 50 minutes. A couple of very kind friends who were very good runners put me in between them. And I ran along with them and I got to 2 49 0 3, which is faster than I could ever otherwise hope to do. And then quite by accident, I became the finish line announcer at the marathon, which was a whole lot easier than running it. So,

Joe Selvaggi:

So, but you can empathize with the with the pain as they come across the finish line. So that that’s right. Now, despite the formidable qualifying times, you talked about the, the awful spectrum having as many as a thousand runners. Now we know in many marathons, I think there’s a thousand marathons around the world. There are some that are 50, 60,000, but Boston’s limited. We’ve only got that little road in Huntington where we start as you say, it all starts here, but down a effectively, a two lane road where you have to get a bunch of people down all of the same time. How how many runners do qualify and how do you limit the race now?

Tom Grilk:

There this year there will be 20,000. We had gotten up to 31,500 prior to the pandemic and, and w we’re limited because the Boston marathon goes through eight different municipalities within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. So there are multiple governmental agencies at multiple levels that have a say in how long we can have the roads, unlike professional sports teams. There is no stadium that we can use. So we are we operate with a good graces of all of those municipalities. And, and they’d like to get their town back when the Boston marathon comes through pretty much everything else stops. It’s hard to even get across the street, although some very creative ways that have been achieved for doing that. And, and so we talk every year informally and very formally with each municipality about what will be acceptable to, to them for that year. And that’s where the field size comes from. The towns are magnificently accommodating but they also need to balance the needs of their citizens and simply people who go go through the cities and towns. So we work very closely with them all the time. And then this year with the advent of the pandemic, that process was followed again with an immense amount of rigor because of the public safety risks presented by the disease,

Joe Selvaggi:

Of course, and beyond, I want to get to the challenges of the pandemic, but again, setting the stage beyond qualified runners. There’s also quite a few charity runners who contribute quite a bit to their respective charities. Can you offer some dimensions on how many charity runners and approximately how much money they’re able to run a raise for their

Tom Grilk:

Well charity runners? The charity program has grown going back all the way to 1989, I think was the very first time that the American liver foundation was the the first official charity of the Boston marathon. And if I look to 2019, the last time we ran on the course had not virtual away, there were 1,575, I believe official charity runners across the BAS zone program. And our principal sponsor John Hancock some of them a great many of them over a thousand,were in the John Hancock nonprofit program. Uthis year we had to cut the field size in order to promote public safety, public health, but we pretty well brought back the same number of charity runners a lot,uhad worked very hard to get ready to run in 2020, and couldn’t do it. Uand the impact of that program,uwhich in 2019, across the John Hancock program at ours approached $40 million. It was 30 and a half or something. Wow.

Tom Grilk:

We didn’t want to see that go away. And those are very difficult choices. What that means is that if we diminish the field size, but don’t diminish the charity field, some qualified runners don’t get to run. And as one who had such a hard time myself qualifying, I understand the frustration that that brings and it’s, it’s never an easy balance. But we wanted to see that the people who work so hard to raise money, had the opportunity to do it. It is of course, very hard to qualify to get into the Boston marathon. It is also very hard to be a charity runner. We establish a limit of at least $5,000. So it needs to be raised on average by every runner for every charity organization. But in fact across the BA program and the John Hancock program, the average amount raised per runner is more like $10,000.

Tom Grilk:

So that means that in addition to training for a marathon, which is hard, you then have to go out. And in many cases pretty well hit up everybody who ever knew for money. And that’s pretty innovating for a lot of people that surely would be for me, great respect for the charity runners, immense respect for the people who qualify and not enough room to have everybody all the time. In theory, we could be getting people out to Hopkinton and just following them down the street all day long, but the towns would be overwhelmed by indeed.

Joe Selvaggi:

So,

Tom Grilk:

So we can go the further into how much of a challenge it is to pull off the Boston marathon. As you say, it’s ordinarily roughly 30,000 runners. It’s eight minutes of municipalities because it’s point to point is from Hopkinton running straight back in. So that’s not that’s every year something like the Normandy invasion all over again. So let’s, let’s do some history here. The Boston is typically or traditionally run on the third, Monday in April. If we go back to 20, 20, March 10th, we had the governor come on and tell us there’s this thing called COVID-19. We had we’re going to have a temporary lockdown to stop or slow the spread. And the marathon was one month away. I’ll admit, I didn’t think the marathon would be canceled, but you were in the front row seat.

Tom Grilk:

You were in the driver’s seat share with our listeners, what it would be, what it was like for you to see the lockdown and know you had this epic event with thousands and thousands of people and millions and millions of dollars of, of money on the line. How did it unfold for you? Well, first remember that the Boston marathon go goes off through the kindness of all the cities and towns and the state and with the initial advent and apparent rapid growth that was coming in COVID, it’s the, the responsibility for public safety resides with governmental officials and they had to take action and they did and interestingly the, the lead in doing that, the, the person who was the convener to get all the municipalities together was then mayor Walsh in Boston. He hosted a couple of meetings in the Eagle room at city hall with representatives of each of the cities and towns and city officials to talk about what would be best for everybody.

Tom Grilk:

It appeared perhaps 10 days before the actual, what happened initially it was a postponement and perhaps 10 days before that a group of all those officials gathered at city hall to talk about the issues and to go back and consider what they thought would be fair to their citizens. And there was another meeting at city hall in which decisions were pretty much made and they were made by consensus. There wasn’t a lot of of wrangling or back and forth. Everyone was aligned on the need to have the event be safe to focus on runners on volunteers and the hundreds of thousands, millions of people who live around here and no one wanted to bring a disease in that could hurt residents. So we finally decided that would happen on I think it was Friday the 13th of March all those representatives once again, got together at Boston city hall. And we going announced that the race would be postponed in those days, we all lived with the hope that the disease would be curtailed, that it would be brought under control somehow or other, which of course it was not.

Joe Selvaggi:

I see. Now I remember that I wasn’t wasn’t qualified and wasn’t planning to run in 2020, but I did run in 2007. And I’m sure you remember, that was the year with the nor’easter and when there was a huge storm coming in and it was going to hit us exactly when the race was to begin and legend has it. And I never actually knew the answer was that they only held the marathon because they were afraid if they canceled it, the runners would show up anyway, and they would run without support. Was there any concern at the BAA with this particular postpone and ultimately cancellation that runners would show up anyway? And if so, did you do anything to sort of discourage that kind of behavior?

Tom Grilk:

Well in the beginning with the marathon postpone, the risk of that happening seemed modest as of Patriot state, but there were certainly publicity campaigns from all public agencies and from us at the BAA saying, please don’t do this. None of us wanted to have the marathon postpone but we’ll look to it in the fall. Let’s all gather together. Then when it’s safe turned out that it couldn’t happen. And there’s always the risk. If, if, if there is a need to, to cancel or to postpone that people will show up anyway it’s, it’s a factor. You can’t rule it out. But in other years, in 2012, when we had a day, that was very, very hot and we knew it was coming and had to decide whether the race could go forward safely or not. As we examine things like the wet bulb globe temperature, which none of us had ever heard of before one of the factors. So as well, if we call it off, people will come anyway. Well, maybe they will, maybe they want if we decide that the right decision is not to hold it. So as to protect you in life then we’ll be able to find a way to keep things safe out on the course. And when I say we, I mean, all the municipalities and state officials,

Joe Selvaggi:

I remember 2012 as well, and it was indeed quite a hot day. I won’t forget that soon. Now as you mentioned, the, the race was initially going to be postponed. Did you effectively have to have all the sort of ducks in a row waiting for the green light? I mean, you can’t just cancel it and say, we’ll see you next year, as you say, you were hoping for a fall, how do you keep all the resources in line? And then ultimately what was going to be the green signal, what was going to be that criteria that said, okay, now it is safe. Do you have weekly meetings or monthly meetings? How does one prepare for something that is so uncertain

Tom Grilk:

Well in the period between April of 2020, and then getting into the summertime when the race was called off entirely, of course there were regular conversations but for us at the BA we follow the lead of public officials. We do all we can to provide them with the information that they need to perform the best analysis they can to tell them what we can do, the mitigation measures that we can put in place. And of course there are a great many that have been put in place now to do it in October. But in the end they decide and there, there are meetings. Th there’s also a great sense of collegiality among all the public officials, public safety officials, and all the people who work on the marathon on the BAA side, which is to say our modest staff of 30 people and the organizing committee of a hundred more and a whole lot of other people who work on it.

Tom Grilk:

And what’s normally the better part of 10,000 volunteers. Everybody gets along and works hard on it. And, and that includes municipal public safety. People’s state people, federal agencies. There’s a whole bunch of federal agencies that get involved. If you watch TV, you know, that federal agencies and local agencies never get along. And all I can say about that in our context is that they never fail to get along. Everybody treats it as their race, and they’re going to do what they can to make it work. And there’s a whole lot of them. Now, there are about 4,000 state, local federal officers, one way or another that, that get involved in this. Some of them, you see some of them you’ll never see.

Joe Selvaggi:

That’s wonderful. So w you who did, was determined that it w the 2020 will effectively be canceled. Now we turn the page and we’re all blessed with this wonderful collection of vaccines that seem to be safe and effective. And we’re a highly vaccinated part of the world. Now, we we see all the lights turning green, and we have decided we can pull off a marathon. Then you’re tasked with, if we’re not going to use the third Monday in April, we’re going to find some other day in the fall. What decisions were around choosing Columbus day naturally the fall is a big time for other marathons historically New York and Chicago, like the fall. What made you pick a Columbus day as the day?

Tom Grilk:

Well, first and foremost, it’s not our choice. What our view was, we could wait until next April and do it then w we don’t have to intrude on other things that, that normally go on. At the same time, if the public officials were welcoming to the idea, we’re happy to do our part, to help reopen society and do do our part in helping to reopen the economy. Just parenthetically this year, we’re doing no large dinners, no post-race party. All of it is involved in sending runners out to eat in restaurants and entertain themselves and other establishments. So we had communications with all of the cities and towns with the Commonwealth to see what for them would be the best time to do it. And it was that Monday in October that was selected.

Joe Selvaggi:

Wonderful. I think it’s great that you characterize the race in the way you do. In other words, it’s not the BAA trying to ask the world to accommodate it, but rather you are facilitating something that belongs to the region, the runners, the, the, the individual towns. In other words, you, you help facilitate something that is is shared and owned by, by everyone. That’s, that’s a wonderful way to look at it. You did mention the the economy. I, I had done some research before the show, and I saw a typical marathon, Boston marathon injects, roughly $200 million into the Boston economy, even a, a smaller one that you’ve planned for the fall. That’s going to have to have a substantially saluatory effect on the economy from Boston to, to Hopkinton any estimate of how how much this will bring to the region.

Tom Grilk:

I, I don’t have an estimate. Normally it’s the greater Boston convention and visitors bureau that does that. They’ve done it for a long time. They do it really well. They’ve also got a whole lot going on right now and all of their normal analytics kind of don’t fit because so much is different. Most notably the number of people coming to run is different. But we’re also changing the things we do. So some things that runners would do some meals, they might get at city hall for the pasta dinner, or going into a post-race party. Well, now they’ll go out into a, a, a local dining establishment and eat there. So I think probably for them, there’s number one, they’re really busy trying to help people who are merchants of all kinds, who are really needed. And, and secondly, just the normal analytics are hard to apply.

Joe Selvaggi:

Let’s talk about again, things that are different about this, this race this first post pandemic race, what safety precautions will the runners need to take. And I, I guess I’ll ask that above and beyond what the town and the city require because those, those are a whole another level as you mentioned, these are tens of thousands of, of runners coming in from all over the world. The runners are typically from the far reaches of the globe. All these people converging on one spot and and getting very close together. I won’t call it a super spreader event, but it’s, it’s, it’s a very difficult thing to control. How will you ensure the runners are kept safe? And of course, the spectators as well?

Tom Grilk:

Well, first off at the, at the very broadest level, we did a survey of everybody, all the runners and all the volunteers, and with a response rate in the 78% rage, a hugely high response rate for any survey somewhere in the range of 95% of both runners and volunteers at, at that time in August that they were or planned to be vaccinated. So just to start with that’s helpful. But that’s all it is, is helpful. It’s indicative what, what will be done is that everyone who comes to run will have to pick up their number, their bid number at the expo at the Heinz convention center, in order to get into the expo, they will either have to show proof of vaccination or a negative COVID test within the proceeding, perhaps 48 hours at that point 72 at the most.

Tom Grilk:

And once they’re able to do that, they will be given a wristband, a colored wristband. It’s kind of like a concert seeing sort of cloth, and it doesn’t come off, but it doesn’t bother you. But the event where that through the race that wristband gets you into the expo and ultimately gets you out to the start. The wristband tells you when to go to the viewer bus on the morning of the race, so that you can get out the content of the proper order, get off the bus and just get going. You know, almost rolling start, which is a big difference this year because of social distancing. We don’t want to have big crowds of people gather and what we have called athlete’s village. I don’t Hopkinton. So as a, as a safety device back way first all runners have to show that they’re either vaccinated or they have have been tested and we will provide tests for those that don’t have them tent set up and they can be tested right there before they go into the expo. But then when the race come and say, we’ll go out as I described in individual buses, get off and go. So that provides a whole lot less density on the course as they run than is normally the case. Usually there are four waves of about 7,500 runners each. So they’re all packed together for a long time to start with. That’s not true this time.

Joe Selvaggi:

That’s interesting. I remember the days when we all went off with a gun and then to the waves start, I was unaware that this is a rolling start. So paint that picture for us. I’m imagining the elites they’re getting on a yellow school bus, like the rest of us. They get out to Hopkinton, I suppose that a bus load of people tow the line and the gun goes off. They start running and as the buses arrive in a Hopkinton rather than go to the athlete’s village, they a mosey on towards the start and, and, and, and one leg when they get there, they, they head off down the course and, and their chip will measure their net time from the start to the finish. Is that more or less what you’re describing?

Tom Grilk:

Exactly. They may want to stop at a comfort station and maybe have a drink of water, but that’s it, other than that,

Joe Selvaggi:

Well, that’s good. I’ll make for less anxiety sitting there thinking about it in the athlete’s village. Now I want to think about this going forward. Do you see now again, the next marathon is going to come up rather quickly and next April do you see these kinds of special procedures persisting, or do you think by then we’ll get a sense of we’ll have a broader vaccination rate or a better sense of let’s say less intrusive ways to to engender a sense of safety.

Tom Grilk:

Yeah, I don’t mean this as frivolous frivolously as it may sound, but I’m a hundred percent certain that we have no idea if there is, if there is one characteristic of this disease, apart from the Schumann tragedy, that it is bright, it is that it is completely unpredictable and uncertain. So w we all hope so we, we will look to April as being more like what had been normal for a number of years. But one, one never knows you hope for the best plan for the worst in date

Joe Selvaggi:

Now we’ve been all Marrathon all the time on this conversation. I want to bring attention to the BAA, being a, a wonderful and frankly, a very elite running club. You don’t just do a marathon. You do, of course the half marathon, usually in the fall. And you do a 5k any support running and runners around the world. You mentioned at the top of the show, the BA used to send champion runners to the Olympics. I hope you aspire to do the same in the future, but tell us a little more about the good work that the BA does for runners and for the region,

Tom Grilk:

The mission for the BA going all the way back to 1887 is in effect to promote health and fitness. And we have it written on the wall. The language has changed some over the years for a long time, that was expressed principally through the conduct of events. The BA was not a particularly well financially endowed enterprise, who we would put on races for people in more recent years. We initiated more community engagement programs, mostly kid focused. So there would be relays for school kids from Boston and schools up and down the course and elsewhere in greater Boston, on marathon weekend in Copley square we have conducted cross country or events that mayor’s cross-country race and other, such things in Franklin park with groups. We have worked with the demic center in Roxbury to assist them as they put on the demic road to wellness 5k.

Tom Grilk:

The first event run walk event in Roxbury that since the 1980s, I think but in general, there’s much more room for us to do better work to engage more and assist more in the communities that have made it possible for us to do what we do in these events felt for us. We see the expansion of our work and community support as what will become our largest area of growth. We’re in the process of working with community leaders to establish something called the Boston or running collaborative in order to, to help people in various communities, principally communities of color to get out and run or walk or move, or do whatever is comfortable for them we will be awarding on this 120 fifth running of the Boston marathon, $125,000 in grants to various community organizations around Boston. And have that be the beginning of such a process going forward.

Joe Selvaggi:

That’s wonderful. I think it was it’s almost an apocryphal story about if if running were a drug it would be the most prescribed drug in the world by doctors. It’s it’s good for you. It’s good for your physical health mental health. And I think it can bring together lots of communities from around the, the, the city, the region. It’s all good work. So we’re getting close to the end of our time together. I have to ask one runner question. This’ll probably help our our downloads. We talked about our your, something that the BA does control entirely for the marathon, which is the qualifying time. As I said, the open time is 3 0 5. Is there any plan in the near future to change that qualifying time either up or down in the foreseeable future,

Tom Grilk:

The selection, the specification, the qualifying time is, is driven by athletes by runners the, the faster they run then the the greater, the qualifying time is, is lowered. And, and we are keenly aware how frustrating that can be for people it’s very hard to to achieve for, for most people and your work and work and work, and you don’t quite get there. And as one who works well and didn’t get there on a number of occasions, I know how that feels. I wish we had more space we don’t, and it would be unfair to try to intrude significantly more on all those cities and towns. So it’s really, it’s the athletes themselves who felt the qualify.

Joe Selvaggi:

So we keep getting faster and you keep lowering the time. Well, I’ll say I’m very proud of the, to have qualified for the marathon. I’ve, I’ve I failed more times than I succeeded, but it was one of the great thrills of my life. I think I’m going to have my BQ at shell, my tombstone. I don’t know if I’m the only guy who feels that way but it’s really a privilege and an honor to have participated in the race and really a privilege and an honor to get a chance to talk with you about the challenges faced by someone at the helm of a very prestigious lead, most prestigious running club on earth. You’ve been very generous to spend some time the race is coming up in a, in a few weeks. Are you ready?

Tom Grilk:

Answer. Yes. Ready in all the normal ways. And normally putting on the Boston marathon is an immensely complicated event this year. It’s more complicated than ever with all of the considerations involving COVID and, and the many, many manifestations of that. It is now we’re down to just sort of more like the putting on the race stuff, the normal stuff, it feels a little more comfortable, but we have had a panel of medical, epidemiological, public safety officials working with us for months and months and months. And the plans have changed on multiple occasions as the nature and effect of the disease changes. So we, we know that we are privileged to have the opportunity to do what we do. And no one knows that more than I do, who gets to do this?

Joe Selvaggi:

Yeah, indeed. It’s a, I’m sure as a runner, it must bring you a thrill to pull this whole thing off. So I look forward to the race on October 11th and I wish you the best of luck and Godspeed and rejoice, we conquer, right.

Tom Grilk:

We’ll try to come to a happier end with those words, perhaps

Joe Selvaggi:

Let’s not drop dead. All right. Well, thank you very much, Tom. You’ve been wonderful. Thanks. Thanks for joining Hubwonk.

Tom Grilk:

Thank you.

Joe Selvaggi:

This has been another episode of Hubwonk, a podcast of Pioneer Institute, a think tank in Boston. If you enjoyed today’s episode, there are several ways to support us. It would be easier for you and better for us. If you subscribe to hub on your iTunes pod catcher, if you want to make it easier for others to find us at hub, you can offer a five-star rating or a glowing review. It’s always helpful if you share us with friends, if you have ideas or suggestions or comments you can reach me at hubwonk@pioneerinstitute.org. Please join me next week for a new episode of Hubwonk.

Recent Episodes: