Why is housing so expensive in Boston?

According to a New York University study, Boston had the third highest median rent in the US behind only Washington DC and San Francisco in 2015. The median price for a single-family house was $725,000 in 2021, which is 14% higher than the price in 2020. The number of houses available in 2021 has fallen by one-third compared to 2020.

A study conducted by The Boston Foundation argues that Greater Boston has not been issuing enough building permits required to meet the growing economy and population since 1980. That may be a defining factor for skyrocketing rents in the city.

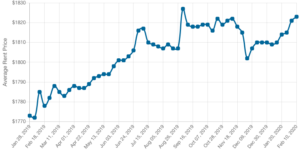

The image depicts the average rent for a studio apartment in Metropolitan Boston from 2019 to 2020 (Source: Boston PADS)

Approving housing permits in Boston is cumbersome due to prevalent zoning practices. Zoning is an urban planning tool that divides land into different zones, with each zone having its own set of regulations and restrictions. It was designed to hinder the construction of manufacturing plants in residential areas.

Over time, zoning practices have been effectively used to build only single-family units that serve a small population. This, combined with the inability to build multiple floors within a house and the enormous time required to obtain construction approval, results in fewer multi-family homes being built.

Zoning also provides local governments with extensive power to decide how to use the property. Residents point to zoning restrictions to exercise control over nearby properties, resulting in fewer houses built on expensive land. One such example is the land near MBTA commuter rail stations, which only has 2.8 houses per acre on average. It is not surprising that between 2010 and 2017, the Boston area added only 71,600 housing units for 245,000 jobs.

Rampant zoning restrictions have severe ramifications. For instance, Boston has one of the highest homelessness rates in the country: The total number of homeless people in families rose by 6.8%, from 3,766 in 2019 to 4,021 in 2020. In November 2020, roughly 161,000 households were struggling to pay the rent.

This scenario leads to high eviction rates, especially in communities of color. Benjamin Walker, a researcher at Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s ??Department of Urban Studies and Planning found that between February 2020 to February 2021, evictions were filed at more than twice the rate for majority-minority neighborhoods as for majority-white neighborhoods.

Experts at the Brookings Institution suggest building more houses in the low-density neighbourhoods near commuter rail stations to combat this crisis. They suggest that Massachusetts employ policies to build homes within a mile of the transit stations. This would have two advantages. First, the proximity to transit stations will reduce commuting costs for the households and combat Boston’s traffic problem. Housing policy expert Amy Dain says that “If an average of five were added annually in each of the 100 area cities and towns, 5,000 new apartments would be created in a decade”.

Second, building more houses will increase the supply of homes in the market, and eventually prices will fall, assuming demand for housing remains similar. Experts at Pioneer Institute and Harvard University have long suggested that providing subsidies to communities that partake in new construction can limit the number of regulations in building multi-family homes. It is imperative to note that COVID-19 may have delayed the action on these policy recommendations because of the budget cuts.

Of course, zoning is not the only reason for increasing housing prices in Boston. But it is clear that there is broad interest in resolving the Boston housing crisis and experts largely agree that zoning reform is a necessary step in the right direction.

Maida Raza is a rising Senior at Earlham College. She is pursuing a Bachelors’s in Economics and Mathematics. Maida is working as a MassEconomix Intern at Pioneer Institute.