Are UMass’ Aggressive Capital Expansion & Out-of-State Recruitment Good for Mass. Students?

Read media coverage of this series: The Boston Globe, The Boston Business Journal, the Associated Press, The Springfield Republican, The Lowell Sun, State House News Service, WAMC

Studies Find Improved UMass Academic Standing and Student Quality May Come at Expense of Commitment to Massachusetts Students

Campuses have seen dramatic rise in enrollment from outside Massachusetts; aggressive capital program drives rising debt and growing maintenance backlog

BOSTON – In recent years the five University of Massachusetts campuses have dramatically increased enrollment and capital spending, improved academic standing and the quality of the students they attract, but a new Pioneer Institute series questions whether the gains have come at the expense of the university’s primary mission to serve in-state students and raises questions about whether the expansion is sustainable in light of mounting debt and projected decreases in the number of Massachusetts high school graduates.

“UMass has much to be proud of in recent years,” said Pioneer Institute Research Director and former Massachusetts Inspector General Greg Sullivan, a co-author of the three-part “UMass at a Crossroads” series. “But there needs to be a vigorous public debate around whether the gains have compromised the university’s mission to serve Massachusetts.”

Overall UMass enrollment increased by 27.3 percent between 2005 and 2014. By comparison, enrollment at other New England state universities rose by 1.7 percent and U.S. public university enrollment rose by 14.4 percent over that period.

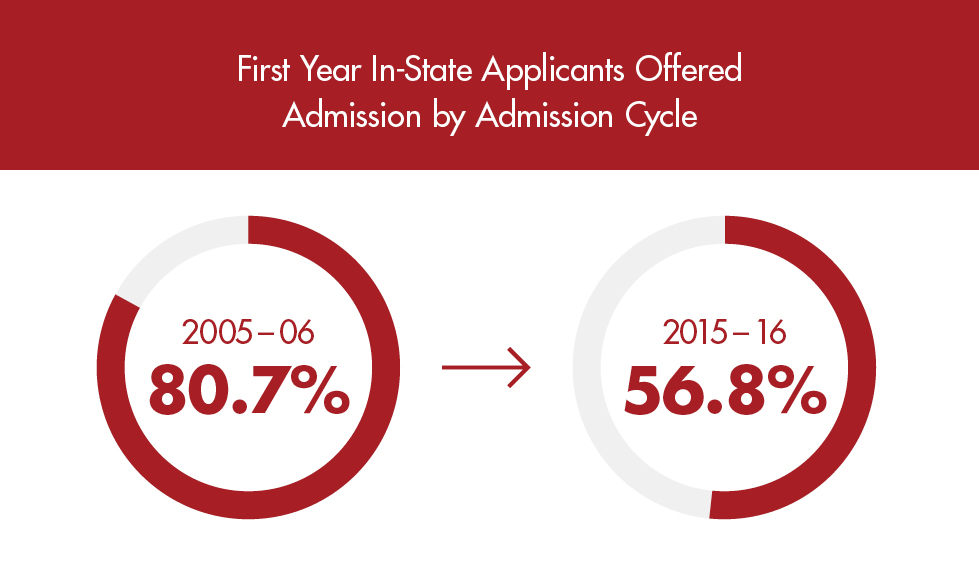

Despite the spike in enrollment, admission to UMass has become far more competitive. In 1992, the average UMass Amherst incoming freshman had a grade point average of 2.92; by 2014, the average had risen to 3.78.

In the five years leading up to 2014, the flagship campus’ ranking rose by more than 20 spots in the U.S. News & World Report ranking of the top 100 national universities.

But Sullivan and co-authors Matthew Blackbourn, Pioneer’s research & operations associate, and Lauren Corvese, research & programs assistant, are concerned that the progress may be achieved at the expense of the university’s central mission of serving the commonwealth.

Rising out-of-state and international enrollment

In 2015, UMass Amherst accepted more freshman from outside Massachusetts than it did in-state applicants for the first time. A decade ago, less than 35 percent of offers of admission went to students from outside Massachusetts.

“In 2015-16, UMass-Amherst crossed an imaginary Rubicon when it accepted more out-of-state than in-state students, and they did it in a year when in-state applications were at a high point,” said Pioneer Institute Executive Director Jim Stergios. “We have to have some hard conversations about the purpose of and strategy for UMass as a public institution.”

Between 2008 and 2014, out-of state enrollment increased by 84.5 percent across UMass campuses, while in-state enrollment grew by 19 percent. The university’s expressed policy is to increase enrollment by 30-40 percent among out-of-state and international students who pay higher prices to attend.

The pursuit of out-of-state students to generate additional revenue is a nationwide trend at public universities, and a contentious one. When out-of-state enrollment at UCLA and UC-Berkeley reached 28.1 percent and 29.1 percent, respectively, of their freshman classes (nearly the same as the 27.9 percent in UMass-Amherst’s most recent freshman class) in 2014, California Governor Jerry Brown and state legislators complained that in-state applicants were being shortchanged. As a result, the university capped those campuses’ out-of-state enrollment at 2014-2015 levels.

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the university Board of Governors limits freshman out-of-state enrollment to 18 percent. At its March 2016 meeting, the board enforced a $1,041,017 penalty against the university after its 2015-2016 out-of-state freshman enrollment exceeded the limit by 1.5 percentage points.

The authors recommend that state leaders consider whether a cap on out-of-state enrollment is appropriate at UMass.

Students from outside Massachusetts make up 70 percent of UMass graduate enrollment. UMass is the only state university in New England in which a majority of graduate students are from out of state.

State higher education officials say the strategy of increasing enrollment of out-of-state students, who pay more to attend, is needed to offset reductions in state support. But state funding for UMass has grown from $478.8 million in FY 2005 to $654.8 this year, roughly tracking the increase in UMass’ operating deficit, which rose from $416.7 million to $709.4 million over the same period.

A metric of state support per full-time equivalent (FTE) student at Massachusetts’ 29 public higher education institutions shows that they receive the second highest level of state support of the six New England state systems. The measure includes state appropriations and fringe benefit payments in state support, but excludes state capital and debt service outlays.

The authors recommend that UMass increase out-of-state tuition. Current UMass Amherst tuition is 5.9 percent below the average of New England state flagship campuses for out-of-state students. The University of Vermont charges $39,130 in tuition and fees for out-of-state undergraduates; UMass charges $8,626 less at $30,504.

UMass has sought to recruit more international students, who also pay out-of-state tuition. From 2008 to 2014, international undergraduate enrollment skyrocketed by more than 300 percent. In-state enrollment increased by 8.8 percent during the same period.

International graduate enrollment rose 55.1 percent over the 2008-2014 timeframe, while in-state graduate enrollment grew by 22.1 percent.

Rising debt, growing maintenance backlog

Increased enrollment has been accompanied by a corresponding jump in capital spending as the campuses carried out a $3.8 billion capital expenditure plan over the last decade.

The commonwealth only paid for $1.38 billion of the expansion program, leaving UMass to finance a majority of the cost with debt and straining university finances. Overall UMass indebtedness grew from $946.2 million to $2.9 billion between fiscal years 2005 and 2016, and annual debt payments grew from $88.5 million to $223.4 million during that time.

UMass’ $6.98 billion FY2015-2019 Capital Plan calls for the pace of capital expansion to accelerate even more. The value of this ambitious plan is equal to about 70 percent of the replacement value of all physical assets on the university’s five campuses.

University trustees have given full approval for 111 projects worth $3.44 billion and preliminary approval to another 97 projects valued at $3.54 billion. No funding source has yet been identified for $3.19 billion of the $6.98 billion plan.

As UMass spent more on capital over the last decade, the university’s deferred maintenance backlog rose from $2.7 billion to $3.33 billion. Sullivan and Blackbourn urge UMass to look to the Massachusetts State College Building Authority (MSCBA), which manages facilities for the nine state colleges, for best practices on how to reduce its maintenance backlog. Between 2000 and 2014, the MSCBA reduced state colleges’ maintenance backlog from $61.1 million to $9 million.

The Facilities Condition Index is the standard measure of higher education facilities management. The state colleges fall in the “Ideal” category on the index, while UMass rates “Very Poor.”

Deferred maintenance and renovation are each slated to make up less than 11 percent of the current $6.98 billion capital plan.

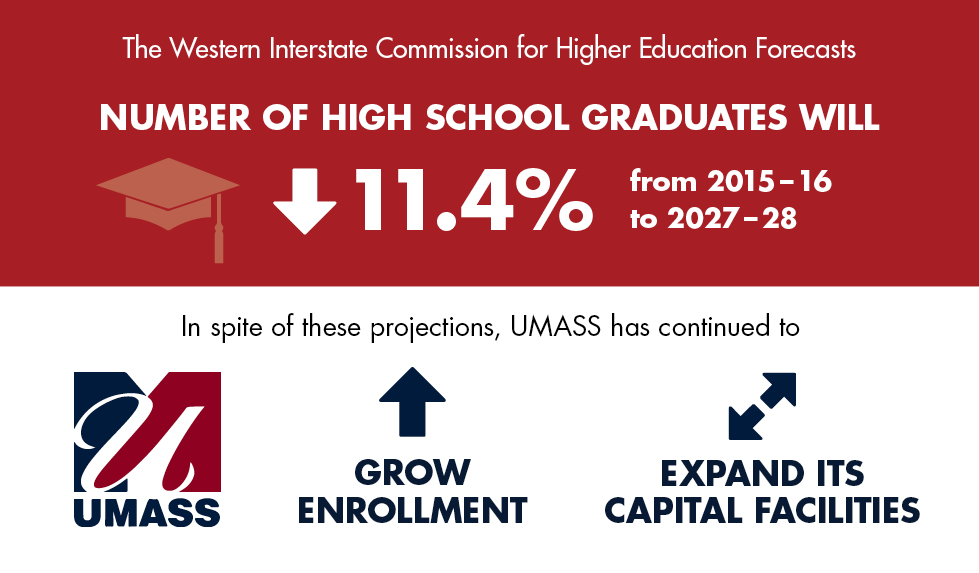

Despite the increased focus on students from outside Massachusetts, demographic projections raise the question of whether the expansion is sustainable. The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education forecasts that the number of high school graduates in Massachusetts will decrease by more than 11 percent over the next 12 years.

About the Authors

Gregory Sullivan is Pioneer Institute’s research director. Prior to joining Pioneer, Sullivan served as state inspector general and was a 17-year member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Greg is a Certified Fraud Investigator, and holds degrees from Harvard College, The Kennedy School of Public Administration, and the Sloan School at MIT.

Matthew Blackbourn is Pioneer’s research & operations associate. He has led projects for the Institute’s Center for Better Government, Center for Economic Opportunity and Health Care Initiative, and assists with managing the organization’s crowdsourcing initiative, the Better Government Competition. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Philosophy from Tulane University, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and graduated summa cum laude.

Lauren Corvese is a 2016 graduate of Northeastern University in Boston, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in political science with minors in business administration and Spanish. Lauren started working at Pioneer through Northeastern’s co-op program in 2015 and has continued as a research assistant.

About Pioneer

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.