Mass. charter schools: No sector like it in the US

In 1992, Pioneer published a book that had the kind of squishy title and wishy-washy message you have all come to expect from Pioneer Institute: “Reinventing the Schools: A Radical Plan for Boston.” Its core message was nested in the dozens of pages of the state’s landmark 1993 Education Reform Act, along with high-quality standards and accountability through teacher and student testing.

Thus began the charter experiment in Massachusetts. How would it turn out?

Public charter schools here as elsewhere were an experiment, the success of which would depend on state policy decisions about how to authorize, hold accountable and expand the emerging charter sector.

Interestingly, in the minds of the Massachusetts Senate and the Governor at the time, charters were an innovation that really did not need to be capped. If the new public charters outperformed district peers, then they would remain open. If not, they would get shut down. So why have any caps?

For political reasons — to get the landmark Reform Law passed –the Massachusetts House required caps. So since that time, when to lift the charter caps and by how much have become perennial debates.

Since 1993 we have seen the charter caps revised and lifted a number of times. Most recently, in January 2010, we saw the allowable percentage of students in the lowest performing districts rise to 18%. And we have seen these seats filled, with Boston and a number of city districts bumping right up against the cap. And some worthy schools already, like the proposed 4th Edward Brooke charter school, were denied largely because we had reached the cap. Think about that – an artificial, adult-made cap kept kids from having access to proven successful schools.

So we are back at it again.

But things are entirely different from the late 90s when this same issue was debated – and different even from the latest go at it in 2009/2010. Then we had good data, but not the kind of data you will see in the presentation from Stanford CREDO’s Edward Cremata (see below).

Last week, Pioneer held an event with Cremata on the most recent CREDO study of charter schools – this one on Massachusetts and Boston charter schools. Authorizing Excellence: Charter Public Schools in Massachusetts, held in partnership with Harvard’s Program on Education Policy & Governance, the Black Alliance for Educational Options, SABIS schools, the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, and the Massachusetts Charter Public School Association, notably featured a keynote from Dr. Howard Fuller, the legendary leader of the movement to create innovative school opportunities and give parents greater voice in the schools their kids go to. The former Superintendent of the Milwaukee Public Schools and Director of the Milwaukee County Department of Health and Human Services is today the Distinguished Professor of Education and Director of the Institute for the Transformation of Learning at Marquette University.

The event featured presentations from the most recent and a robust panel discussion/debate moderated by former Virginia and Florida superintendent/commissioner Gerard Robinson, with panelists Jeannie Allen, Medford Superintendent Roy Belson, Cara Stillings Candal and the Shanker Institute’s Leo Casey.

Cremata’s presentation builds on numerous studies, including those commissioned by The Boston Foundation and New Schools Venture Fund, Pioneer, the Department of Education, and on and on, all showing the remarkable success of the Massachusetts and Boston charter sectors.

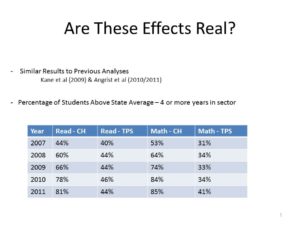

The entire slide deck is worth spending time on. But let me pull out two slides that got my attention. The first, slide 22, asks how real the outsized effects of charter schools are in Massachusetts. It notes that however good the Boston and Massachusetts charters were in 2007, they are only getting better and better. A charter student with four years in the charter sector in 2007 was 44% of the time above the statewide average for reading and 53% of the time above the statewide average in math (compared to 40% and 31% in the district system). By 2011, those numbers skyrocketed to 81% and 85%, respectively in the charter sector, while the district school percentages had gone up slightly from 40 to 44% for reading and 31 to 41% in math.

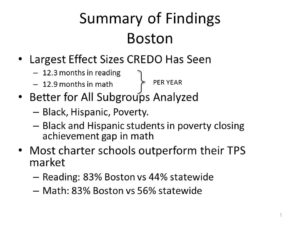

Then there is this summary slide of the results in Boston charter schools. The first bullet is an incredible result, with Boston charters providing and addition 12 months of learning in reading and 13 months of math learning each year.

Again, the entire slide deck is well worth your time.

And Dr. Fuller was on fire, debating issues like why there are caps on charter schools at all (especially in the Bay State where the performance is unquestionably high). He discussed how the charter sector needs to grow African-American leaders, to preserve its “movement” feel by not buying into bureaucratic restrictions such as those whereby only “proven providers” are allowed to get charters, and more.

[youtube height=”HEIGHT” width=”WIDTH”]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rAukOn6i8uk[/youtube]

These issues are incredibly important in Massachusetts, where the legislature has begun to tie down the charter sector with regulations and restrictions. That was the central theme of the Authorizing Excellence, at which Pioneer released “Looking Back to Move Forward,” authored by Candal, senior fellow at the Institute. Candal’s paper looks back at the history of charter authorizations in order to draw lessons for changes that will address weaknesses in our current process. Massachusetts was once the home to what was considered one of the best authorization processes in the country. We set the bar. Today, there are questions about the autonomy of the state’s Charter School Office and the potential politicization of a few recent chartering decisions. Candal looks at the processes in other states and makes recommendations.

In a nutshell, Candal’s thesis is that Massachusetts should abolish charter public school caps, create a more autonomous Charter School Office and explore the creation of additional charter authorizers. As Candal noted,

Charter schools have been a success story in Massachusetts, but the charter authorizing process has become more politicized and is being used to subject charters to the same kind of regulation as traditional schools.

Candal also finds that giving the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s Charter School Office (CSO) the kind of autonomy it once had would allow the experts to make decisions about charter authorization.

It would also help to prevent situations like one that occurred in 2009, when state Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education Mitchell Chester recommended that the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE) approve a Gloucester charter school despite a CSO finding that the school didn’t meet the commonwealth’s criteria. The Gloucester Community Arts Charter School has subsequently closed.

Contrast that with the arbitrary BESE decision not to approve a SABIS International proposal to create a high-performing school in Brockton. It was knocked down not only in 2008 but once again in the most recent authorization cycle. How is it possible that in one of the lowest-performing districts the BESE could view SABIS, which runs two highly successful charters in Springfield and Holyoke, as unworthy of replication? The fact is, as a for-profit provider, the school is not ideologically viewed favorably by the BESE or the DESE. Sigh.

Her call for multiple charter authorizers might also limit politicization and reduce the burden on the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), which forwards its findings to the BESE. The board is currently the only charter authorizer in Massachusetts

Candal points out that multiple charter authorizers might also encourage innovation after the 2010 law’s unfortunate requirement that new charters in low-performing Massachusetts school districts be operated by “proven providers” with an established record of success. She recommends eliminating the proven-provider requirement, which would likely encourage innovation and increase the number of high quality charter schools. Over time, the proven provider requirement could result in a group of schools that are similar in terms of educational mission and even programming.

The event, presentations and debate were all extremely timely given that in the current legislative session, there is a bill filed in the House and the Senate to lift the cap on public charters in the 10 percent worst performing districts – that’s a total of 29 districts in all. About a quarter of the students in Massachusetts are in those districts.

Given the incredible performance of Massachusetts charters and the fact that there are tens of thousands of inner city children on the wait lists to get in to the existing charters, this legislation needs to move forward. Commissioner Chester’s call to wait another three years before doing something is unacceptable. Why?

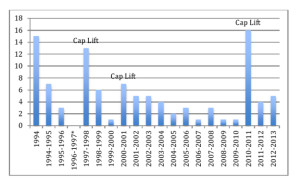

Compare the tens of thousands of kids on the wait lists to the tiny incremental increases we are seeing charter schools. The chart below, from Candal’s paper makes it very clear that the state’s approval of 4 and 5 new charters in 2011-12 and 2012-13, respectively, is insufficient to the need.

Figure 1: Number of Charters Approved in MA, 1994-2013

Follow me on twitter at @jimstergios, or visit Pioneer’s website.