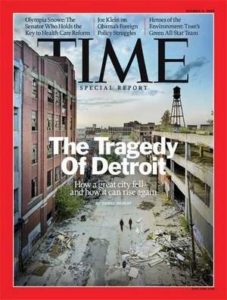

Is Detroit coming to Massachusetts’ cities?

Anybody who expects a Chapter 9 filing in Massachusetts in the next couple of years does not know what he or she is talking about. Feel better now? You shouldn’t.

Not that I want it to occur — hardly the case as it is painful, unfair, and proof that our political institutions are showing rot.

Here are some basic facts on Detroit’s Chapter 9 filing and what it means for Massachusetts.

Chapter 9 is not a frequent occurrence, and Detroit’s filing should not lead us to expect a wave of Chapter 9 filings. Only a few states allow it. It’s tough medicine. Chapter 9 wipes clean the past – all pension deals, all bargained wage agreements can be rendered null and void.

Massachusetts cities are not in the same immediate danger as Detroit, which is spending 42% of its annual budget on public employee pensions, and will be spending 65% by 2017. That’s in essence why the Motor City has chosen to take the path of Chapter 9. Some of its issues of ungovernability (tens of thousands of street lights that don’t work, thousands of builds that are vacant) remind me of aspects of the Springfield “soft receivership.” That soft receivership model, in this case meaning the establishment of state oversight boards with some enhanced powers, is one that Massachusetts has used with some success. It helped Chelsea get back on its feet — as it did for Springfield which went from $41 million in the red to $17 million in the black in its first 18 months of existence.

Usually in place for terms of 3 to 6 years, Massachusetts’ use of state oversight boards can help clean up the messes made by poor management in our cities, but BUT don’t solve their core issues.

The challenges that Massachusetts cities like Lawrence, Springfield, Fall River and New Bedford face are two:

First, 30 years ago these cities were not wealthy, but today they are unsustainably poor. The average income in these cities used to be around 85% of the statewide average – so they were less wealthy, yes, but not poor. Today, the average income is more like 65%, which means that there is little money and little business for cities to build a future on. So the state is forced to provide over half the annual budget for four cities currently in Massachusetts. That’s a dangerous place to be.

Second, the collective bargaining agreements and pension systems are unsustainable. Springfield’s is funded at 30% — which means that a lot of empty promises have been made and that city workers may not have a safety net of support for their retirement. It also means that a lot more money has to be pumped into funding them. That’s where over a longer period of time, Springfield and Lawrence start to look a lot more like Detroit – and run the same risks.

Follow me on twitter at @jimstergios, visit Pioneer’s website, or check out our education posts at the Rock The Schoolhouse blog.