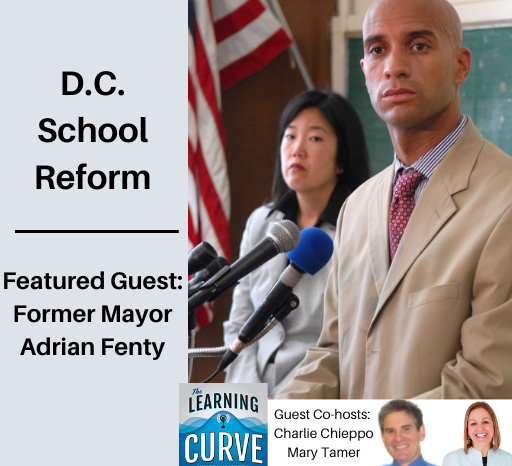

Former D.C. Mayor Adrian Fenty on School Reform

/in Featured, Learning Curve, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

[00:00:00] Charlie: [00:01:00] Well, hello everybody and welcome to this week’s edition of the Learning Curve . My name is Charlie Chieppo. I am a senior fellow at Pioneer Institute and I’m going to be your guest co-host this week and I’m very glad to say that here co-hosting with me is Mary Tamer. So Mary, tell us a little about you and welcome.

[00:01:22] Mary: Thanks so much, Charlie. I’m really happy to be back again. I am the executive director of Democrats for Education Reform Massachusetts and our affiliate is education reform now and we work at the nexus of advocacy policy and politics. We’re a national organization and I am proud to be leading up the statewide work here in Massachusetts.

[00:01:47] Charlie: Well, Mary, I suspect there’s a lot going on at that particular nexus. You have plenty to do. All right, well, we are going to jump into our stories for this week. This week, mine is kind of a, has kind of a personal angle to it. The federal government is launching a review of whether Massachusetts adequately supports students with disabilities and properly oversees the network of about a hundred special education schools that serve students whose needs can’t be met in their traditional public school.

[00:02:21] Charlie: I’m a parent of two special needs kids and my answer to whether the state is adequately supporting those students and whether they are appropriately overseeing those hundred special education schools is sometimes. Looking at the stories about the announcement of this review, quote from the founder of a special needs advocacy group really jumped out at me.

[00:02:47] Charlie: She said, we have many students who are struggling socially, struggling with mental health issues that are comparing their ability to perform in school. These struggles have been going on for years for these students and [00:03:00] districts do nothing. It’s absolutely horrible.

[00:03:02] Charlie: Well, I can tell you that is sometimes true. I know from my own experience; you have to hire. Advocates and lawyers basically you know, my family couldn’t really afford them but that’s what you need to do to get the district to move and, you know, of course, you can’t help but wonder what’s it like for people who are less fortunate than my family and who are, less involved with the system and less able to navigate it than my family was, in my son’s case, it culminated with weeks of him not being able to attend school and actually being hospitalized before the district agreed to the placement that he needed.

[00:03:41] Charlie: In my daughter’s case she had a special education teacher who really bordered on being abusive. And, you know, she attended a couple of SPED schools, one of which was pretty highly dysfunctional. Now, on the other hand, when my son got his placement, the school was great and he really flourished and after five years in special education schools, my daughter made what I thought was really, I’m bragging here, a courageous decision, which is what she decided to come back to the local high school for her senior year in the midst of the pandemic.

[00:04:15] Charlie: And she also flourished that year in no small part because the SPED support that she got was fantastic. So, I’m personally going to be very interested in seeing the results of this review, and I hope that it can help bring about a system that is more stable and more consistent to serve the students who need it.

[00:04:36] Mary: I am with you 150 percent on this, Charlie. That story was a devastating read and in your own personal experience, and I want to say as someone who has been a staunch advocate for students with disabilities, and this dates back to my time serving on the Boston School Committee starting in 2010 under Mayor Menino.

[00:04:57] Mary: The number one phone call, the number one email [00:05:00] I received had to do with parents who were seeking help for their children because IEPs weren’t being followed because their child needed a private placement and they couldn’t hire the lawyer or they didn’t know what are the steps I need to go through in order to get that placement for my child.

[00:05:17] Mary: And so, these situations are so fraught with emotion. And we all want the best for our children. And I think when we are parenting children who fall into more vulnerable categories and to realize that some of these children, too many frankly, are not being given the services and care that they need and deserve in order to be successful.

[00:05:44] Mary: It’s devastating. I mean, you know, better than anyone, these private placement schools are very expensive, which is why families are put in a position of having to lawyer up in order to get one of these coveted placements. And so, to see that oversight has not been where it should be in terms of our students at a time when we know that even our most vulnerable students have faced insurmountable odds and obstacles over these last several years of disrupted learning. It really was a very, very difficult story to read and to really contemplate right now.

[00:06:22] Charlie: Yeah, you bring a good point because my you know, the stuff my kids went through was before the pandemic. And I can only imagine. What that’s like now. I mean, let’s face it. We certainly can’t entirely blame the schools. There’s a lot of blame to go around with the pandemic, but that I’m sure is not better now than it was when my kids went through it.

[00:06:42] Mary: So, I think that’s true, Charlie. I think that, again, you know, even though my term ended quite a number of years ago, I will still hear consistently from families who are seeking help for their children. And I would say the number one issue that I’m hearing about [00:07:00] is increasing levels of anxiety, even for students who didn’t have anxiety prior to the pandemic and school based anxiety in particular, the fear of going to school and it really and then you know, even in a wonderful city like Boston, people can be on wait lists for six months or more trying to get the right services for their child.

[00:07:21] Charlie: I didn’t experience that fear of going to school until I got to law school. That’s when it hit me. But anyway, that’s, that’s a different story.

[00:07:28] Mary: Yeah. Well, my story this week is something that we continue to hear a positive thing that we’re hearing about it. Unfortunately, there’s lots of different opinions about what we do to fix the problem of literacy in the United States, specifically the fact that far too many of our children our young children are not reading on grade level.

[00:07:53] Mary: And so, this particular article talked about the national landscape and references [00:08:00] the National Assessment of Educational Progress, also known as NAEP or the Nation’s Report Card. Which is showing us that about one third of American fourth graders are reading at or below what’s considered a basic level.

[00:08:15] Mary: This is not new. I think there are lots of folks who would like to say this is as a result of the pandemic and disrupted learning. But in fact, we’ve been seeing downward trends for a while even since the early 1990s. And so, what they’re seeing, Charlie, is that scores increase slightly as children get older, but not by much.

[00:08:39] Mary: And in the eighth grade, about a fourth of students do not read at what’s considered the basic achievement level. And the percentage stays about the same. for high schoolers. And so, for those folks that don’t work in education like we do, you know, this is really concerning because if a child is not reading on grade level by third grade, that’s the telltale year because that’s when children are expected to flip from learning how to read to reading to learn.

[00:09:11] Mary: And so, if you’re not at that benchmark by third grade, you are in catch up mode and it just gets harder and harder and harder for students to catch up. And so-called reading wars that we are continuing to hear about, and there’s a wonderful podcast by reporter Emily Hannaford called Sold a Story. And it talks about the move away from phonics-based instruction, which is how I learned how to read many decades ago, and there’s been a transition to different reading instructions, including something called balanced literacy, which has made millions and millions of dollars for the folks that crafted that and for the publishers who sell it to school districts. But that’s a system where kids are literally being shown a photograph and being asked to guess what it is versus giving them phonetic awareness by you know, sounding out letters sounding out words and figuring out what words are even if we don’t know what they are.

[00:10:16] Mary: And so, there’s a wonderful woman who I’ve had the pleasure to meet Dr. Kymyona Burk. Um, She’s Mississippi’s former literacy director. She’s currently with the education nonprofit ExcelInEd. And she is traveling to the country and basically telling states. What their outlook looks like, which in many cases is not good and she talks about you know, that the strategies utilized by something like a balanced literacy is really not benefiting students.

[00:10:48] Mary: And so, one of the things that, you know, when Dr. Burk was in charge of literacy efforts in the state of Mississippi, Mississippi was at the very bottom. of the country. So, they were ranked [00:11:00] 50th. I believe now Mississippi is 21st in the country. That is a significant gain. And I know from when Dr. Burk came and presented here in Massachusetts and gave the literacy outlook specifically for black students in the state of Massachusetts, where only 17 percent of black students in grades three through eight in Massachusetts are reading on grade level.

[00:11:25] Mary: And what Dr. Burk showed us is that black students in Mississippi and in Florida in the same grades are surpassing Massachusetts students when it comes to reading outcomes. So, we have a lot of work to do not just here but across the country as well.

[00:11:44] Charlie: Well, you know, that is such a important and good issue and would also say I think it dovetails with our guest today because in looking at some of the data, I believe if I remember correctly that it is really Mississippi, as well as Washington, D. C., obviously the place where our guest today Mayor Adrian Fenty was the mayor 2007 to 2011, have really been among the states that have improved the fastest in reading in recent years. So, I suspect that maybe we are going to hear a little bit more about that today. So, coming up after the break, as I said, we have former D.C. Mayor Adrian Fenty. [00:13:00]

[00:13:51] Charlie: Adrian Fenty is the founding managing partner at Mac Venture Capital. Prior to MacVenture, Adrian was co-founder and managing partner at M. Ventures and [00:14:00] special advisor to Andreessen Horowitz. He began his tech career as a consultant to Rosetta Stone, EverFi, and several software startups. Mr. Fenty served as the sixth mayor of the District of Columbia, holding office from 2007 to 2011. Education reform was a major focus of his mayoral tenure, during which he introduced legislation to restructure control of the public schools. A D.C. native, Fenty earned a BA in English and Economics at Oberlin College, and a JD from the Howard University School of Law. Adrian Fenty, welcome to the Learning Curve. We’re pleased to have you.

[00:14:36] Adrian: Hey, thank you so much for having me.

[00:14:39] Charlie: So, let’s jump right in. During your term as mayor the D.C. public schools both their growth on NAEP and the reforms your administration implemented were historic. What part of your legacy of reforming the D.C. public schools are you most proud of and what was the most difficult part of the job as mayor?

[00:14:58] Adrian: Well, I’m most proud that we changed the law and that we took over the school system and put it under the mayor. I think all jurisdictions should do that. School boards are inefficient, they don’t get anything done and there just is no room for not getting anything done in public education, including Washington D.C. which still has, you know, so much to do.

[00:15:23] Adrian: So, the only thing that I’m satisfied with the fact that we took over the system and that we show that it’s a really high priority, our highest priority in Washington D.C. Other than that, we just have a tremendous amount of work to do. And so do all the other jurisdictions with poor kids who are not learning at grade levels. It’s just terrible.

[00:15:47] Charlie: No doubt about it. I’m just curious, before you were able to pass that legislation, I mean, was the mayor essentially an onlooker, or, you know, could sort of just had a bully pulpit, but that was about it in terms of [00:16:00] management of the school system?

[00:16:01] Adrian: Well, yeah, that’s the case in every jurisdiction except Washington, D.C. Chicago, and New York — mayor has no formal role. That being said, all mayors should do something, even if they’re just causing, you know, raising holy hell and showing how bad the schools are and trying to shame the school boards into doing something. I just watched so many mayors doing like their whole terms go by, and they do absolutely nothing about education. I don’t even understand it. I don’t understand why the citizens let them do it too.

[00:16:34] Charlie: Well, that’s a whole other issue. The fact that so many people, you know, list education as one of their highest priorities, but so few people, seem to vote based on education, but that’s a, that’s a topic.

[00:16:47] Adrian: Well, people have education as their highest priority for themselves and their own kids. There’s no question about it. Like if you know, any active parent, they spend so much time [00:17:00] thinking about their kid’s education and their kid’s teacher and how much kids doing their homework. But they don’t hold the government accountable for educating children, even though if you just draw the connection, there’s no point in really thinking that we’re going to have any impact on poverty and crime and making someone’s life better if you don’t have a great education. So, we just need to have the same priorities for our cities that we have for our own households.

[00:17:36] Charlie: Yeah. No, that’s well said. Well, you know, you certainly took action. You, one of the things you did, of course, was that you decided to hire and you, you know, consistently backed Michelle Rhee, who had a notoriously plain spoken, aggressive management style that focused on results for kids. Could you talk about how entrenched the school system was, and why you and Reid decided that proactive leadership was the [00:18:00] best way to cut through the bureaucracy and politics that so often stifles urban reform?

[00:18:05] Adrian: Washington, D.C. in every way, you know, when we took over the system it was a disaster. I mean, the year before we took over the system, 20 schools had to close in the middle of the winter because they didn’t have sufficient heat. that was 2006 in the nation’s capital, the United States of America.

[00:18:28] Adrian: I mean, you want to name, you want to name anything, the kids, teachers didn’t get their paychecks in time, the kids didn’t get their immunization shots in time, like the toilets didn’t work, roofs leaked, there’s no toilet paper, there’s graffiti everywhere, the air conditioning didn’t work, heating didn’t work, just on and on and on and on, and that was just the easy to understand physical apparatus and operations of this system in terms of education.

[00:18:58] Adrian: I mean, it’s not, it wasn’t unlikely to go into a middle school and your kids would be 13 or 14 years old and they’d be five grade levels behind in reading and math. Something that’s still the case in a ton of urban jurisdictions today. So, it’s just. I don’t know. I just don’t understand the lack of sense of urgency and the lack of focus on education. I mean, people run around saying the homicide rates are high and, you know, crime is high and, you know, and there’s problems. Of course there are, you know, there’s like thousands of kids, that we just let go for decades at a time without any education. So, when they get to be in high school, you know, they drop out, they’re not skilled to get a job, they’re gonna get into a life of trouble and life of crime. And these are the same, you know, adolescents and older people who cause trouble, but it’s like, I’m in the Twilight Zone because it happens cyclically. You know what I mean?[00:20:00]

[00:20:00] Adrian: We did everything 2007, it’s 16 years later and there’s absolutely nothing different. All the politicians either ignore it or they pay lip service to education. And you, some of you guys are Democrats for Education Reform. I mean, the Democrats are a disaster. I’m a Democrat, but they’re a disaster. No Democrat has any inclination to do anything for schools. And if you’re not going to do anything for urban schools, then you’re not going to do anything for poor kids. Because there’s nothing you can do on the back end to make up for not, not providing an education. So, if you’re down with the special interests, whose number one priority is to make life better for adults in the school system, and you give second priority to the education of the kids, then you’re not part of the solution.

[00:20:51] Adrian: Yeah. And that’s the Democratic Party that we have known all the way back to the Clintons and it continues all the way up to [00:21:00] today with Biden and the Democrats who run Congress and the governors in this country. Our party is terrible on education, which means we’re terrible on poor people. And because that’s the only thing that’s going to be a solution.

[00:21:16] Charlie: Well, let’s talk about some of those special interests. Teachers unions are often blamed for being the major barrier to reform, but you already talked about how the school committee performed before you were able to get control of public education in D.C. You know, and in many cities’ urban districts, there’s city councils to deal with central offices that are resistant to improvement and efficiency. How did your administration deal with this sort of municipal central office sort of internal resistance to city school reform?

[00:21:48] Adrian: Well, we took over the system. So we, yeah. So, I mean, once, once we took over the system, the bureaucrats reported to us, we replaced 40 years of bureaucracy [00:22:00] essentially with Michelle Rhee, which that fixed it overnight. Which is what should happen in every city, and we eliminated the Board of Education, and I became Board of Education, and yet a City Council has oversight, you know, and that’s real, there’s real oversight in the City Council, but a City Council that does its job correctly, sets standards, approves a budget and does oversight, but they don’t get into the day-to-day management of a school system. And that’s the difference between the mayor running the school system and having the city council who provides diligent oversight and having a school board, which has to make a decision on everything.

[00:22:41] Adrian: On every little small decision in the school system, and when you have a, that may work if you had a school system that was, operating at an A-plus level, but when the school system is broken and you need to make, you know, a hundred major fixes, you can’t have a school board in control because they’ll never approve anything,

[00:22:58] Adrian: First of all, they’re too slow. Second of all, all the decisions are controversial. They’ll never make controversial decisions because they will lose their job and they don’t want to lose their job.

[00:23:09] Charlie: Yeah, not to mention the sort of political implications involved in so many of those decisions. yeah, interesting. So, in addition to district schools, D.C. is also home to a significant number of charter public schools and a now long-standing federal voucher program. Could you talk about the relationship and the tensions and dynamics between the sort of in-district public school reforms and the different types of private and public-school choices in D.C.

[00:23:37] Adrian: Well, the bottom line is that whatever your position on charters and vouchers, there’s still on the margins, the bulk of the kids in Washington, D.C., and certainly the bulk of the kids in the country are in traditional public schools. So, either you fix the traditional public schools and we can start having a real discussion about kids learning, or you don’t fix the traditional public schools, and it doesn’t matter what you do with charter schools and vouchers, because it’s just on the margins, and you’re still going to have the lion’s share of kids growing up in Detroit, LA, Chicago, Atlanta, who aren’t getting… a good education.

[00:24:19] Adrian: And that’s the bottom line. So, I love what Michelle did. She was like, we support charter schools. We support vouchers, but it has nothing to do with the job we need to do in a traditional public school. The traditional public school is really broken, and we need to fix it. And that’s the bottom line.

[00:24:39] Adrian: The charters are too incremental. You’ll never, you’ll never be able to like have a charter system that turns around a city, but you can, you could turn around a city. if you fix the traditional public school system, if you made sure the traditional public school system That every kid had the opportunity to get to [00:25:00] read and do math on grade level and go to college, if you did that, which is, of course, as we just talked about, that’s everybody’s goal for their own kids.

[00:25:08] Adrian: If you did that, that would turn around cities dramatically from crime to jobs to taxes to everything. That this country would flourish in an amazing way.

[00:25:24] Mary: Yeah, I share your frustration. Mayor Fenty and the lack of awareness around the crisis that so many of our students are facing as a result of not being well served in their public schools and the role that the Democratic Party does play in that. And, you know, I know Charlie mentioned that you did hire Michelle Rhee who was an incredible change maker.

[00:25:50] Mary: She hired Kaya Henderson, who succeeded Rhee as the head of the D. C. public schools and Rhee and Henderson had differing, although equally effective management styles. Could you talk about their two approaches to K to 12 educational leadership and how your administration worked to hand off the reform efforts of the D. C. public schools to the next administration?

[00:26:23] Adrian: I’ll say two things. So, the only way to run something, anything that is as broken as the D. C. public school system was in June of 2000 and seven, when we took over is to hire the best managers possible and to make really fast, aggressive, controversial decisions. People understand when something’s really broken, you have to be really aggressive in fixing it.

[00:26:53] Adrian: But it’s really hard for people to feel comfortable about it. I, it’s a real kind of a quandary, but there’s nothing easy about it. You can’t do it incrementally. You can’t do it and make people happy. None of that will happen. All of that will just ensure that nothing changes.

[00:27:13] Adrian: The only way to do it is to make a series of really aggressive decisions fast. And even if you do all of that, it’s still going to take time. Years for the system to turn itself around and if you don’t do those things you have no chance that is my position on what type of person should run a school system someone who is courageous and willing to make really tough decisions that everybody knows needs to be made in terms of turning the system over I didn’t do anything to turn the system over. When I lost my reelection it was time for the next people to turn the job to do the job and it’s up to the citizens to view how they did that job, but once you’re out, you’re out.

[00:27:53] Adrian: Yep. I mean, I mean, I mean, as long as I was mayor, I made decisions as aggressive as I could until the day I walked out of the office in August of 2010, a month before I was up for reelection. We fired 250 teachers at the cost. Only the second time that I understand in this country that teachers have ever been fired for cause. The first time was when we did it a year or two before knowing we were going in for a real action a month before. That is the decision we made. And then once I lost the reelection, it was up to whoever, it was up to Gray and his administration to make decisions for the city after that.

[00:28:35] Mary: So, we know, and you’ve made it very clear that urban school districts have been in crisis. Before COVID-19, which only revealed deeper weaknesses in our large public education systems. Could you share your thoughts on and perhaps even give a grade for how well you think national education leaders, mayors, governors, [00:29:00] state chiefs, and local officials have addressed America’s ongoing crisis in urban K to 12 education. I think you’ve already answered this, but if you were to give a grade, what would it be?

[00:29:14] Mary: And I’d like to probe deeper if we could on why is there a lack of political will to address this? What is holding people back from talking about the elephant in the room? Whether it’s our kids not being able to read, on grade level, not being able to do math. What is happening that is preventing elected leaders from doing something more meaningful about what you and I and Charlie are seeing before us?

[00:29:47] Adrian: There’s a few different levels to this, but at its core, they don’t care enough. For sure, people care. But do you care enough? That’s the bottom line. And like Yuval Harari, I just heard him on a podcast, he has this great thing. He says, there are mathematical problems that cannot be fixed, that cannot be solved, right? That is a fact. He says, but there are no policy questions that cannot be solved. He says, to solve a policy question, the only thing you need is motivation. That is the point.

[00:30:25] Adrian: So, put it like this. If it were their own kids for people who know what to do, if it was their own kids, they would absolutely make sure that their kids. Read on grade level, do math on grade level, don’t drop out, graduate from high school, and go to college. Because if you do all those things, you are ensuring that your kids have the greatest chance to succeed in society.

[00:30:51] Adrian: And if you don’t do those things… There’s a much higher chance that your own kid, if they didn’t graduate from high school or they didn’t read on grade level, that your own kid would not be able to get a job or would become, could become a criminal or, get into drugs. So just, so what Michelle used to, her whole thesis on running our system was that we should just run the system for the kids as if they were our own kids. Make the decision that you would for our own kids. And once you do that, you stop thinking about all these adult issues. The only thing that matters is kids’ ssues. But there are some other answers to your question.

[00:31:29] Adrian: The other thing is, so probably another reason why you get away with it is because these are poor kids. There are no wealthy kids who are three, four or five grade levels behind, it doesn’t happen. It happens in poor neighborhoods in our country. And it happens because people don’t care as much and there’s not as much advocacy. That’s immoral, because everybody knows what should be done. And then, like we said before, you can’t blame the teacher’s union. The teachers [00:32:00] union is just set up to support teachers. That’s literally their job.

[00:32:05] Adrian: But you have to wonder, who empowers the teachers’ union? It’s the Democratic Party. There literally is no leader in the Democratic Party that you can think of in the Senate, in a governor’s position, in the White House. The last three Democratic presidents, none of them have done anything material to change education. None of them have put their jobs on the line. None of them have said, listen, we know that education is the only thing that’s going to interrupt the cycle of poverty. I am going to be the education president. None of them have done that. And we just let them do it. And they talk about everything else except for, leading on education.

[00:32:48] Mary: That leads me to my next question about some of the shifts that we’ve seen when it comes to the politics of the teacher’s union specifically. And so, for decades, you know, I think the teachers unions were center left, although most often considered establishment institutions in major American cities.

[00:33:07] Mary: And over the last five to seven years, we’ve seen, you know, the national teachers’ unions and their big city urban affiliates adopt a far further left political platform. So, could you talk about this shift within the teachers unions and in larger American cities and what does it mean for urban school reform in the United States right now?

[00:33:29] Adrian: I’m going to just keep it simple because I can’t get into the whole, all the complexities of policy because that’s not important in running a school system. Here’s what’s important in running a school system. Can you hold somebody accountable? If you can’t hold anybody accountable, then you have no hope of having a well-managed organization, right?

[00:33:50] Adrian: You certainly have no hope of turning around a poorly run organization. And here’s the bottom line. Here’s why the Democratic Party’s blanket support [00:34:00] of teachers’ unions is a problem — because the template for the collective bargaining agreement reads as follows: We are going to hire a teacher. And if the teacher can stay in that position for two years, then they are automatically granted tenure. And once they automatically get tenure, they can never be fired. That is not an exaggeration or hyperbole. They can never be fired. Okay. and not only can they never be fired, but the only way also that they can get more money or get promoted is by seniority.

[00:34:33] Adrian: So you have essentially eliminated any accountability for the education of the children, for the people who are responsible for educating the children. Now, lots of people like to say, okay, well, then you’re blaming the teachers for lots of societal problems. No, that’s not, that’s not the point.

[00:34:51] Adrian: The point is, if you have a system where you get tenure, In two years, which basically is automatic tenure. And then that tenure means you can never be [00:35:00] fired and you’re promoted just based on seniority, not based on how good did you do the job? In any profession, if you did that, the work product of the employee would go down tremendously.

[00:35:10] Adrian: And that is what happens in schools. It happens in our most important place, but it would happen anywhere. It would happen in tech. It would happen in finance. It would happen in Hollywood. It would happen in education. If you just gave people more money just for working, just for being in the job, they would do a worse job.

[00:35:31] Adrian: So we’re promoting a system where people get paid no matter what job they do exactly the same, just for sticking around. In essence, that is the biggest problem in public education and all the policy discussions and all that other stuff that all the politicians like to talk about pales in comparison to that.

[00:35:53] Mary: Yeah. it’s definitely I think one of the biggest problems we face.

[00:35:58] Adrian: And all the people who the Democrats for Education Reform support, they support that collective bargaining agreement. That is a problem. Democrats for Education Reform should not support any candidate who supports a collective bargaining agreement. The problem is, if you said, I’m not going to support anybody who supports that collective bargaining agreement, you wouldn’t support anybody. Cause they all support it, but you have to draw the line at some point, the Democrats for Education Reform, and I understand some of you are members of it, can’t have it both ways.

[00:36:31] Adrian: You can’t be for education reform and support these incrementalists who are supporting everything, that the teachers union is okay with or that doesn’t really change the system in a fast period of time. We have to call out our party. Our party knows what needs to be done in education reform.

[00:36:49] Adrian: It knows that poor kids will never learn unless we lengthen the school day, and you can hold teachers accountable, and you can close down schools that aren’t working and lots of other things. Our kids will never learn. And so, if you’re just going to support the teachers’ union, Democratic Party, well, then we’re not going to support you.

[00:37:09] Mary: Yeah, well, that brings us to our last question specifically around education reform and how do we get it done in our big cities like D. C. Because you know how difficult it is to get these changes made. Yet you managed to navigate D.C. politics and to deliver pretty outstanding results for kids. So, could you talk about the types of fundamental reforms you think larger cities and urban school districts across America should be undertaking, or does it have to start with that collective bargaining agreement?

[00:37:49] Adrian: Well, it probably has to start with, the mayor’s office, to be honest with you, because everything else is just like the way Michael Bloomberg said it to me when we were talking about this before I took over the system, he said, listen, if you have nine people in charge, essentially a school board.

[00:38:05] Adrian: If you have nine people who are running something, that means no one’s running it. And when he said that it was so clear in my mind, and I must have repeated it a thousand times. It’s so true. The only way to have anything work is to have one person in charge, and either that person is doing a great job, and you keep them there, or they’re not, and you get rid of them.

[00:38:25] Adrian: But with a school board in charge, it’s never going to work. So, you have to get rid of the school board, and you have to put the mayor in charge. And however, that happens, That’s up to the city. It probably has to happen, you know, through some kind of charter change or the governor puts the mayor in control.

[00:38:42] Adrian: But if you’re just going to keep a school board in control, nothing’s going to change. And so, it goes back to what Yuval Harari said, there’s no policy problem that can’t be fixed. It just takes motivation. And what I like to say is, people need to care. And everyone says they care about education, but do they? You know what I mean? How much time do they spend thinking about it? Is their number one priority? Do they elect democratic mayors and democratic governors and senators and presidents who never do anything about education?

[00:39:14] Mary: Too often? Yes, I think that’s probably the case.

[00:39:17] Adrian: No, not too often all the time all the time all the time the entire democratic Congress, both the house of representatives and the Senate, like the entire, there’s not one Congress person or Senator that you can name, please do. If you, if you can think of one, there’s not one that you can name who is willing to take a stand against the Teachers Unions control of the education system.

[00:39:43] Adrian: Not Clinton, not Biden, not Obama. Thank you very much. Not any governor, not any senator currently there. Not if they’re a Democrat, they’re not. Not the Congressional Black Caucus, no one. Not the Hispanic Caucus, if they’re a Democrat, their positions are locked with the [00:40:00] Democratic Party, and I’m a Democrat.

[00:40:02] Adrian: I was elected Democrat, and I’m telling you, know how it is, and it’s, not only, it’s not only terrible, it’s immoral. I mean, because most of these people know what has to be done, and they look right in the face of a difficult decision, and they do the opposite, which means it’s immoral.

[00:40:20] Adrian: They shouldn’t have their jobs.

[00:40:21] Charlie: Mayor Fenney, Charlie Chieppo again. Just, I’m curious, was that your experience? That you felt like most of these folks, or a good number of these folks, knew very well that that was the case and just to do otherwise.

[00:40:34] Adrian: Absolutely. It certainly was true of the Obama administration, because the Obama administration in their first year did race to the top.

[00:40:46] Adrian: Do you remember the race to the top? Sure, sure. Yeah. And we won the race to the top. So, this is not a gripe at all. Under Rhee, we won the race to the top. But after the first year, they got so much flak from [00:41:00] Pelosi and Reid and all the democratic leaders who are supported by the teachers union and they got so much flack in their own administration that they never did it again.

[00:41:10] Adrian: And they were in office for seven years after that. And they do nothing on the, nothing material on education. Race to the Top said we are going to allow urban school systems to come up with innovative ways to change how they do education, and if they do, we are going to grant them money. Terrific policy.

[00:41:29] Adrian: Probably as much as you can do in the Department of Education, to be honest with you. And they did it! And as soon as they did it, they got so much flak from the Teachers Union, and they started worrying about reelection and everything else, that they never did it again.

[00:41:44] Charlie: Well, that is a sobering, a sobering fact to leave us with Mayor Fenty. But boy, you’ve given us a lot to think about today, and we really appreciate your… Being part of the learning curve and giving us a little time and being our guest. So, thank you so much.

[00:41:59] Adrian: [00:42:00] Thank you guys for having me on.

[00:42:29] Charlie: Well, in my story this week, I sort of spoke from a parental point of view, and I’m going to do the same thing with this week’s tweet of the week. This is 1 that I think that pretty much every parent, has wrestled with it is from us news education and the tweet is should cell phones be allowed in schools answering that question often depends on the school or even the specific teacher and it has link to a US news story on that topic, which is certainly what I’m going to read.

[00:42:57] Charlie: So, I. Urge you to do the [00:43:00] same. So Mary, I just want to say thank you. It is such a pleasure to do these podcasts with you. I always learn a lot and learn more. Thanks for your input and your good questions. So, thank you. I hope you will join us again.

[00:43:12] Mary: Absolutely. Charlie, thank you for having me always willing and more than happy to talk about education with you.

[00:43:17] Charlie: All right, great. Well, likewise. And next week on The Learning Curve, our guest will be Jeff Broadwater, Professor Emeritus of History at Barton College and the author of George Mason, Forgotten Founder. Hope you’ll join us again next week.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest co-hosts Charlie Chieppo and Mary Tamer of DFER- Massachusetts interview former D.C. Mayor Adrian Fenty. Mayor Fenty discusses the historic school reforms implemented during his and Michelle Rhee’s tenure in Washington, D.C., focusing on taking over the D.C. Public Schools (DCPS). He highlights the challenges of overcoming the DCPS bureaucracy, navigating politics, and managing the transition of leadership from Michelle Rhee to Kaya Henderson. Additionally, Mayor Fenty touches on the broader crisis of urban education reform and teacher unions’ role in controlling the urban school landscape.

Stories of the Week: Charlie discussed a story from WBUR about the federal review in Massachusetts assessing support for students with disabilities and oversight of special education. Mary focused on a story from ABC News emphasizing the alarming literacy crisis in American schooling. It highlights the ongoing debate over instructional methods, with concerns about the effectiveness of whole language and balanced literacy.

Guest:

Adrian Fenty is the founding managing partner at MaC Venture Capital. Prior to MaC, Adrian was co-founder and Managing Partner at M. Ventures and Special Advisor to Andreessen Horowitz. He began his tech career as a consultant to Rosetta Stone, EverFi and several software startups. Mr. Fenty served as the sixth mayor of the District of Columbia, holding office from 2007-2011. Education reform was a major focus of his mayoral tenure, during which he introduced legislation to restructure control of the public schools. A D.C. native, Fenty earned a B.A. in English and economics at Oberlin College and a J.D. from the Howard University School of Law.

Tweet of the Week:

https://x.com/USNewsEducation/status/1710352358754926778?s=20