Survey Finds Prescription Drug Prices Easy To Access, But Not Always Accurate

Wide variation found in price of generics, less for brand-name drugs; consumers must navigate difficult terrain to find lowest price

BOSTON – It’s far easier to get prescription drug price information than to get similar numbers from hospitals or specialty physicians, but the information is not always reliable, according to a new survey published by Pioneer Institute.

Researchers called 44 independent and chain drugstores across Massachusetts and asked for a 30-day supply in a common dosage of five generic and three brand-name drugs. Callers said they were self-pay and pressed the stores for information about discounts. Massachusetts’ 2012 state law mandating price transparency does not cover retail pharmaceutical sales.

“There were virtually no transfers or dropped calls, no lengthy hold or wait times, and most of our callers were treated with courtesy,” said Barbara Anthony, primary author of “Transparency in Retail Drug Prices: Easy to Obtain but Accuracy May Be Doubtful.” “However some workers weren’t well informed about the pharmacy’s discount programs and those working in chain stores didn’t refer the callers to drug discount program information on their websites.”

Although most Massachusetts residents have health insurance, between 3 and 4 percent are uninsured at any given time. Combine that with the rise of high-deductible insurance plans and those who are underinsured, and the result is that many consumers are paying out-of-pocket for all or part of their prescription drugs.

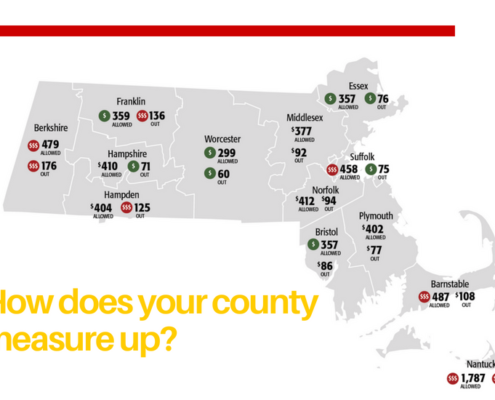

There was significant variation among drugstores in the price of generic drugs, which account for 87 percent of prescriptions filled in the U.S. and typically cost one-third to one-tenth the price of brand-name drugs.

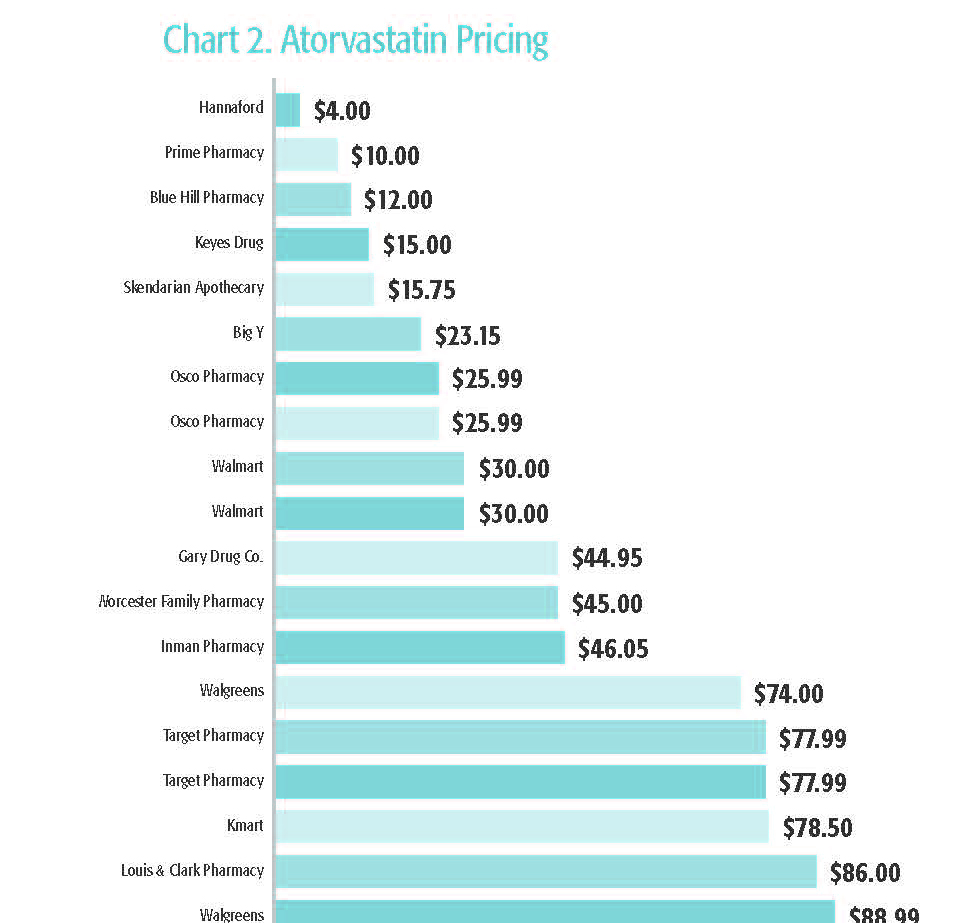

Atorvastatin, a popular generic used to control cholesterol, cost $4 at a pharmacy in Lunenburg and just under $199 at one in Boston.

See full chart in report.

There was a much narrower range for the three brand-name drugs about which researchers inquired.

Manufacturers’ coupons and those from companies like GoodRx and OneRx were found to reduce prices significantly for some generic drugs like Atorvastatin and Montelukast, a substitute for the antihistamine Singulair. But the coupon price was sometimes higher than the price using store discounts for other drugs.

“Finding the lowest price, even among generic drugs, is tough terrain for consumers to navigate,” Anthony said. “Consumers need to consult coupon websites, call stores, shop, compare and try to find the best price at a time they are already in a vulnerable position,” she added.

The value of coupons was also mixed for brand-name drugs. Using GoodRx reduced the price of Patanol, a popular eye-drop medication, from $335 to $268 at Walgreens, but provided little savings on other drugs.

It was often difficult to get accurate price information over the phone. Sometimes drugstores couldn’t verify the price of a drug using a discount coupon until the transaction was run through the store’s computer system. Some major chains will only disclose a “phantom” or average wholesale price for a drug because their computer systems are not able to provide the true price unless the prescription is actually processed.

“Consumers can’t be expected to physically go from pharmacy to pharmacy to get an accurate price,” said Pioneer’s Executive Director Jim Stergios.

The authors make several recommendations:

- Pharmacy workers should receive better training about communicating prescription drug discount programs and they should refer customers to store websites, where applicable, for more information.

- Retail drug stores should do more to inform consumers that they accept discount coupons.

- Store computer systems need to be more consumer friendly and generate accurate prices to consumers who are shopping by phone; the inability to give an accurate price without filling the script impedes transparency and hurts consumers.

- Consumers should not automatically assume that chain store prices are lower than independent drug store prices, and should know that many independent stores are willing to negotiate to match price. Shopping around can save money even on generic drugs.

- Consumers should search the internet for discount drug coupons but they should not automatically assume that all coupon prices represent the best possible deal.

- Prescription drug payers should adopt the level of transparency used by the Medicare program. There, beneficiaries receive an easy-to-read monthly report showing the amount Medicare paid to the pharmacy for each drug, the amount paid by the beneficiary and pharmacy payments from any other payers.

About the Authors

Barbara Anthony, a lawyer, is a senior fellow in healthcare at Pioneer Institute focusing on healthcare price and quality transparency. She is also an associate at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Center for Business and Government. She served as Massachusetts Undersecretary for Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation from 2009 to 2015.

Scott Haller graduated from Northeastern University with a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science. He started working at Pioneer Institute through the Northeastern’s Co-op Program and continues now as the Lovett C. Peters Fellow in Healthcare. He previously worked at the Office of the Inspector General.

About Pioneer

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.

Get Updates On Our Healthcare Cost Transparency Initiative!

Related Research