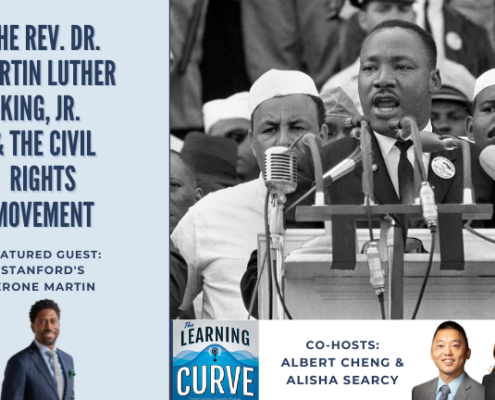

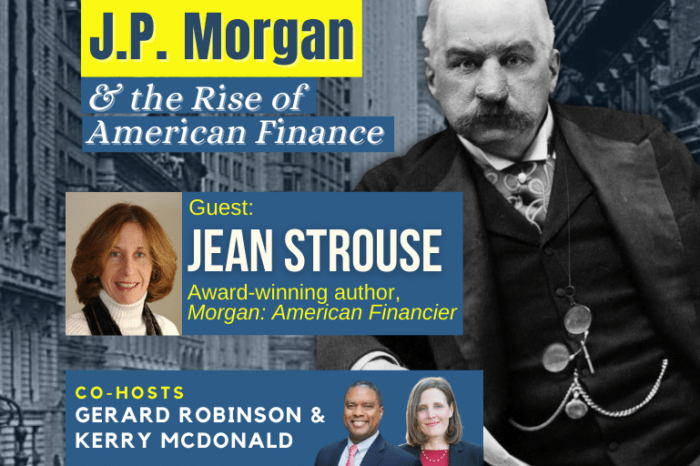

Jean Strouse on J.P. Morgan & the Rise of American Finance

/in Featured, Podcast, US History /by Editorial Staff

This week on “The Learning Curve,” Gerard Robinson and guest co-host Kerry McDonald talk with Jean Strouse, author of the award-winning biography of J.P. Morgan, Morgan: American Financier. They discuss why the general public and students alike should know more about the life and accomplishments of the controversial, late 19th- and early 20th-century American banker. She explains Morgan’s role as a stabilizing figure while serving as the de facto central bank during financial booms and panics, and his importance in the creation of U.S. Steel, Edison General Electric, and the railroad empire, all of which helped propel the nation’s economic ascent. He was also involved in public disputes with Theodore Roosevelt and other Progressive-era figures over the power of business trusts and monopolies. Finally, Ms. Strouse describes Morgan’s famous art collecting, and one of the most interesting figures in his life, Belle da Costa Greene, who was director of the world-renowned Pierpont Morgan Library. The interview concludes with Ms. Strouse’s reading from her biography of J.P. Morgan.

Stories of the Week: Survey data show more Americans are considering foregoing college in favor of alternatives to career pathways, and enrollment has not seen a post-COVID rebound. For those families who do plan for college, U.S. News offers some tips, including starting the search early, talking to recruiters, learning effective study habits, and more.

Guest

Jean Strouse is the author of Morgan: American Financier and Alice James: A Biography, which won the Bancroft Prize in American History and Diplomacy. Her essays and reviews have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, Newsweek, Architectural Digest, and Slate. She has been President of the Society of American Historians, a consultant (oral historian) to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and a Fellow of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the Executive Council of the Authors Guild, she was the Sue Ann and John Weinberg Director of the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at The New York Public Library from 2003 to 2017. She is currently writing a book about John Singer Sargent’s twelve portraits of the family of Asher Wertheimer, a prominent London art dealer.

Jean Strouse is the author of Morgan: American Financier and Alice James: A Biography, which won the Bancroft Prize in American History and Diplomacy. Her essays and reviews have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, Newsweek, Architectural Digest, and Slate. She has been President of the Society of American Historians, a consultant (oral historian) to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and a Fellow of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the Executive Council of the Authors Guild, she was the Sue Ann and John Weinberg Director of the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at The New York Public Library from 2003 to 2017. She is currently writing a book about John Singer Sargent’s twelve portraits of the family of Asher Wertheimer, a prominent London art dealer.

The next episode will air on Weds., July 20th, with Bernita Bradley, the founder of Engaged Detroit, a parent-driven urban school reform advocacy network.

Tweet of the Week:

Virtual reality in the classroom may sound complicated to master, expensive to implement, and generally more trouble than it is worth.

But those are misconceptions, said two teachers who regularly use the technology in their classrooms. #EdTechhttps://t.co/ER4pPBiCXX

— Education Week (@educationweek) June 28, 2022

News Links:

Is college worth it? Americans say they value higher education, but it’s too expensive for many

Tips for Starting the College Search

https://www.usnews.com/education/articles/tips-for-starting-the-college-search

Get new episodes of The Learning Curve in your inbox!

Read a Transcript of This Episode

Please excuse typos.

[00:00:00] GR: Hello listeners. This is Gerard Robinson talking to you from beautiful Charlottesville, Virginia. I am joined by Kerry McDonald, who’s a senior education fellow, , at fee and is also an author. Of a book called unschooled, raising curious, well, educated children outside the conventional classroom, as well as just being a really good cohost when Cara is off, telling us she’s working hard, probably doing something.

[00:00:49] That’s probably unimportant to what we do here, but it’s always good to have you join me, Kerry.

[00:00:54] Kerry: It’s always a pleasure to be with you, Gerard. Thanks for having me.

[00:00:59] GR: Yep. And I’m [00:01:00] sure that when Cara hears this, I’ll get a nice, , email text from her. So I always like to add her on when she’s not here. And as you know, she’ll do the same.

[00:01:07] So we’ve had a lot, , that’s taken place since the last time we were able to co-host, a show together and we always pick really interesting stories. , I’ll kick it over to you to talk about your story of.

[00:01:19] Yeah. So I think both of us this week, Gerard are talking about college. This is the theme of the week.

[00:01:25] And of course, , a lot of college campuses will begin their fall semesters in just another month. So it’s probably good that we’re talking about this now, but the article this week is in USA today. An article called is college worth it. Americans say they value higher education, but it’s too expensive for many.

[00:01:44] And then it went through some survey data around, Americans saying that, they may forgo college because of the expense. And it reminded me of a recent New York times article, from just a few weeks ago that also, reported that college enrollment is [00:02:00] down. And of course, during.

[00:02:01] Disruptive 20, 20, 20, 21 academic year, public school enrollment was down and college enrollment was down and there was an expectation that that would rebound say previous, this previous academic year, 2021 to 2022, it didn’t rebound, quickly, particularly in, public school districts that remained, shuttered for longer or.

[00:02:23] Had ongoing sort of COVID policies and the same seems to be true for colleges according to New York times that found that, , college enrollment dropped for over four and a half percent. this previous academic year, in graduate school enrollment also declined. And I thought it was interesting that certainly the costs of college are a key factor, the financial burden of college loans and so on.

[00:02:46] But one of the things that the New York times article pointed out that I didn’t see as much in the U S a a today piece is the idea that college students. You know, are looking at the benefits and costs, not only financial, but also opportunity [00:03:00] costs and realizing now that there are, other attractive, , opportunities for them outside of college, that they don’t necessarily need a college degree, to get a good job.

[00:03:08] A lot of tech companies now don’t require a college degree. There’s, various apprenticeship programs. I recently interviewed in my podcast, the CEO of Praxis, which is an established apprenticeship program that helps. College age students create kind of alternative signaling methods to, let employers know that they have the skills and competencies to be successful on the job without having to, go into debt with college loans.

[00:03:34] So just an interesting topic, thinking about Americans, maybe questioning college and, and perhaps considering some alternatives.

[00:03:41] GR: That’s a great story. it reminds me of a report, that was published by education trust one of many, and they took a good deep dive into PE students. And as you know, PE is the largest, , government based investment in higher education.

[00:03:58] The country. Particularly for low [00:04:00] income and working class families. and they found that while some schools are doing really well, too many first generation Pell grant eligible students, are not completing college at all, or if they do, , beyond the four year term, many going in after six years.

[00:04:16] And so when I hear this, , two things come to mind, one, exactly what you mentioned earlier. That there are pathways to economic prosperity and social mobility, that don’t require a college diploma or post-secondary degree. In some instances, a high school diploma, a G E D and or even, , stackable credentials, , can play a role.

[00:04:39] So for listeners, I would say, we’ve gotta think about this when we’re talking about trying to make college available for and affordable. For, lower income students, but we also have to be very cognizant. There are a lot of challenges once they arrive. And then number two, are we sending too many?

[00:04:58] Under prepared students to [00:05:00] college. So even if money isn’t a factor, let’s say, , you’ve got a 5 29 plan. let’s say someone gave you a great scholarship. So let’s just take money off the table. There’s still a number of students who are going to college and enrolling in remediation, or remedial education courses.

[00:05:18] And again, for some student, First generation, , it may take 1, 2, 3 semesters to complete it. Even if money isn’t a factor. And again, we’re just holding everything. Even you still have the fact that you’ve earned, credits that in fact are not college. Eligible credits for you to graduate. So I do think we as a nation need to rethink, , what college means, , why we’re sending students to college and who should go.

[00:05:45] And I’ve said on this show before, if, , our two younger daughters decide after high school, not to go directly to college. I am okay with that. So thank you for that story. mine is similar. it’s also from us news and world report, and [00:06:00] mine is a story about people who are going to search for college.

[00:06:02] And so I’ve got, the middle daughter is going into high school this year and the conversation about college, what it could look like, even the conversation of. Decide you wanna do something different? That started two years ago. I am a first in my family to graduate from college. A college conversation really didn’t begin in our household until my sophomore year.

[00:06:25] And that was more focused on playing football as a entree into college, not one based upon academics. So I started really late. So when I read, the tips that are put together, This article is by Sammy Allen and his title tips for starting the college search from planning early to seeking now scholarships.

[00:06:42] These seven tips will help you find a good college fit. And so number one is planning early and having. And worked in the school reform space for nearly 30 years. I can tell you many parents have not had a honest conversation with themselves, their family, or their child about [00:07:00] what college should look like until they’re in high school.

[00:07:03] So one recommendation from Paul Payton, who is in assistant director of admissions at Claplan university of South Carolina, one of our HBCUs, she said beginning. College selection process. And the ninth grade, gives students four years to search every college that you feel you. to be a part of this also gives you a chance to talk to recruiters and college planning experts, and also set up long term goals.

[00:07:26] So start at least in the ninth grade, tip number two, know yourself. , there is a VP of enrollment management and retention at, Jarson Christian university. And what he said is students need to know themselves what they. What their interests are, how they learn best and how they thrive. , the VP said that too many students in fact, allow their parents understandably so to push kids automatically to their Alma mater, , because you wanna keep tradition or they let students choose schools.

[00:07:59] That [00:08:00] sound great, but may not be a good fit. So I would definitely say know your. And this is particularly true based upon research. I read several years ago that said the average college student changes, heres or her major seven times. And some of that is doing to not knowing myself going in beforehand.

[00:08:17] tip number three, take college level courses in high school. , for those of you who have children enrolled in AP classes, , who have students taking, , college level courses, we get it. And so ranking who’s the person I mentioned earlier, he says, high achievement in those college level courses, give colleges a look at your transcript and give you an idea of how well you are going to likely succeed in college.

[00:08:41] And so that part is true. You and I also know there’s a current debate amongst admissions officers on how much weight do we put on the number of classes students take their AP and some would say inflated GPAs. at some point they’re. We’re getting a lot of students with a 4.6, they’ve taken all the right [00:09:00] courses.

[00:09:00] How do we differentiate, , Gerard, from Kara or Jamie or someone else? And so taking college level courses is surely one pathway to do that. And then. Some other factors will come into play. the next is develop disciplined study habits. So this is something that most of us did not learn even in college.

[00:09:22] And so here ranking is saying, you need to learn those study habits in high school, and it’s not simply. Sitting at the table, with a computer or with a book open, doing a lot of highlighting on the book or doing it on your handheld device. It really is a discipline of learning how to study. You know, one of my mentors, he died several years ago.

[00:09:44] He was a professor at, El Camino community college in Los Angeles where I earned my associate’s degree and he created a company called the study skills. I. Why? Well, he worked as a professor with his doctorate from Pepperdine. He worked with a number of students, [00:10:00] but he had college friends who said, listen, too many of the students you’re sending to me.

[00:10:05] Have no great study skills. They’re saying that I can’t teach it here, but someone’s got to. And so he created a business to work with not only low income and middle income, but high income, college educated parents who had households who said, yep. My student needs to learn how to study. So study habits are great.

[00:10:23] , the next is do your research. If you wanna become a veterinarian, for example, Talk to someone in the field. If you wanna become an entrepreneur, talk to someone in the field. I believe that’s very true. Now I earned my degree from Howard university and philosophy. I can tell you there was no professional philosopher I could have talked to at the time.

[00:10:40] Although there was several people I know who like to P philosophy for free, and I would definitely go to them for advice, whether it’s helpful or in that, another story, off the number six in terms of tips. It is pursue scholarships to limit borrowing. , that’s true for the reasons, you just mentioned, uh, before, and should also look for specialized scholarships.

[00:10:59] There are public and [00:11:00] private universities that have money for students who are from certain states. there are scholarships for people who have a particular interest in a one aspect of the humanities or the social sciences. So I would say definitely look and last, find your. And this is from Angela Sharp.

[00:11:16] She’s a counselor at park hill, south high school in Missouri. And Angela says technology today allows us to view pictures, videos, and even take virtual tours, but nothing compares to an actual college visit. And so she also said, when a student walks on a campus, they get the full, , gut feeling that says, yes, this is it.

[00:11:39] Or maybe this is just. Okay. And so I agree with her, for a host of reasons. There are some students who in fact, may not have an opportunity to travel to a college campus because , , they don’t have the funds to make it happen. And I know that there are actually foundations who. provide money to send students to college tours on the east coast, they’ll travel on a bus, let’s say [00:12:00] from DC to Florida, or they’ll go north to new England, uh, where you’re located, but there are foundations who can make this happen.

[00:12:06] So look for that. So these are. R seven, tips provided and be interested in getting your thoughts.

[00:12:13] Yeah. This was such an interesting us news article, Gerard. I really liked the piece on scholarships, particularly merit based scholarships , and there was a link in this article in the article link will be in the show notes.

[00:12:27] , but in the section on scholarships, there’s a link that to a site, another us news website, all about college scholarships, particularly merit based scholarships, which are, grants that don’t need to be paid back. They’re not loans. And there were some incredible articles there, resources there for families to explore, including a list of, I think it was 13 colleges that are known for giving the most.

[00:12:52] Merit based scholarships, more than 50% of their, , applicants end up getting these merit based [00:13:00] scholarships. So some great resources there.

[00:13:02] GR: Absolutely. And for our listeners who are members, , of one or two professional, uh, gender based or academic. Sororities fraternities or associations. , they too have scholarships and they often go, , underutilized, , because people don’t know that these sororities, fraternities, associations in fact have scholarships for them.

[00:13:22] So thanks for that. who do we have today? Who’s gonna come on board and join us.

[00:13:28] today on the podcast, we have Jean Strouse coming on. I’m really excited to talk to her about her book on JP Morgan. Of course, the iconic banker, around the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And just a fascinating look at a fascinating person in American history.

[00:13:49] GR: Yeah. I look forward to the conversation as well, because as a young college student, whenever I heard JP Morgan and at the time I was, majoring in business, just a, Titan [00:14:00] of capital, a Titan of industry would come to mind, but as we’ll learn, those are just two traits, but there’s so much more to him.

[00:14:08] And so much more to his influence, not only on finance, but on American society as well. And given that we currently live in an environment where at least in my opinion, there seems to be a rise in anti-free market, ideas or, anti-capitalism, it’s good. Every now and then hear from guests who will give us a different perspective on what people do, , in this work.

[00:14:30] So look

[00:14:31] forward to our talking to, I agree. Yeah. Really looking forward to our conversation with Ms. Strouse.[00:15:00]

[00:15:44] GR: Welcome[00:16:00]

[00:16:12] back to the learning. Podcast. We are joined by Jean Strouse, who is the author of Morgan: American Financer and Alice James: A Biography, which won the Bancroft prize in American history and diplomacy for essays and reviews have appeared in the new Yorker, the New York review of book. The New York times, Newsweek architectural digest and slate.

[00:16:37] She has been the president of the society of American historians, a consultant oral historian to the bill of Melinda gates foundation and a fellow of the John D and Catherine T MacArthur foundation. A member of the American academy of arts and sciences, the American philosophical society, and the executive council of the authors Guild.

[00:16:58] She was the Sue Ann and [00:17:00] John Weinberg, director of the Dorothy and Lewis B Coleman center for scholars and writers at the New York public library from 2003 to 2017. She is currently writing a book about John singer. Sergeant’s 12 portraits of the family of Asher word Heimer, a prominent London art dealer, Ms.

[00:17:19] Strouse. Welcome to the learning curve podcast.

[00:17:22] Jean: Thank you so much. It’s pleasure to be here.

[00:17:25] It’s great to have you here. So I wanna talk a little bit more about your book on JP Morgan, in the late 19th and early 20th century, JP Morgan was the most important and iconic banker in the world. Could you share with our listeners who he was?

[00:17:42] What were some of his major accomplishments in finance and why? The general public and students alike should know more about this colosus of American economic history.

[00:17:53] Jean: , he was born into what in America was the upper class or the [00:18:00] Patricia class.

[00:18:00] This is his both on both sides of his family had been here since, before the revolution. He was born in Hartford, Connecticut grew up there and partially in, and then went to Europe with the family. When he was about 15 was educated in Switzerland and Germany and came back to start his banking career in 1857.

[00:18:19] Over the next 40 50 years. He basically, and we’ll talk later about how this came about, but he was acting as the unofficial central banker of the United States working with his father in London. there was no central bank here for his entire lifetime from 1836 to 1913. And so there was not much control over this exclusively growing, new economy that quick soon by the end of the century had become the.

[00:18:46] Powerful industrial economy in the world. There were panics and crashes every 10 years. John Kenneth gall said they happened whenever the last generation had forgotten about them. There was another one. and he was trying to [00:19:00] prevent those and then also deal with them when they did happen, cuz nobody could completely prevent them.

[00:19:06] In the course of, that work. , he. A unique role in American history in American economic history. trying to control the excesses of the business cycle, which as we know today are not very controllable. And there was no sense that the government should be doing that.

[00:19:25] There was not yet a federal reserve as I think I just said. And, , the idea that one man, , could take, take it upon himself to try. Do that is quite an extraordinary idea. He organized major, industrial corporations for years. He was trying to reorganize and stabilize the railroads, which were the most important thing going on in the American economy for the most of the last third of the 19th century.

[00:19:54] they were enormously expensive to build and there wasn’t enough money in the us to build them. [00:20:00] so the money had to come from abroad. and Morgan and his father working together in London and New York were raising the funds in Europe to build the American railroad infrastructure, took a long time.

[00:20:12] and. Railroad corporate companies weren’t able to produce profits until the track has been track had been laid down and the, cars began rolling and, commerce began traveling on the tracks and it was enormously complicated and enormous. There was a lot of competition among the railroads and Morgan was trying to sort of straighten that out and, , Control the excesses of that wildly competitive wildly expensive wildly chaotic marketplace.

[00:20:40] And by the 1890s he had more or less, , consolidated the major railroad systems and moved on to create us steel international harvester, general electric and the modern form of at and T. So it was a big life and iconic. Banker, as you [00:21:00] said, and many people saluted him as, , a great organizer and.

[00:21:07] far seeing figure, and of course, many people opposed to anybody having that much power and especially that much economic power America really freaked out at the idea of the trusts and at the idea of these robber barons as they were called, these big bankers and industrialists who amassed enormous fortunes and, we’re seen as the embodiment of evil.

[00:21:31] So it was very contr. So you

[00:21:34] GR: mentioned

[00:21:35] that JP Morgan was really the central banker, before there was, , a central bank and it really brought up some of the conflicts, , the dating back to the country’s founding, you know, from the founding of the Republic, there were these tensions between the Hamiltonian.

[00:21:51] And the Jeffersonian visions of America. So I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about that, about the 19th century economic fights over the [00:22:00] national bank and the financial booms and panics. You’ve mentioned that JP Morgan tried to be a stabilizing figure in that process, but I’m curious if you can dig a little bit deeper into, , what that process was like in terms of creating a national bank and JP Morgan’s role in.

[00:22:16] Jean: Yes. , Andrew Jackson had destroyed, effectively destroyed the second bank of the United States in 1836. , it was very controversial whether the country needed that kind of unifying economic, power and resource and, Jackson. And the Southern and many other people thought not. and Morgan was born the following year in 1837.

[00:22:42] so there was, as I said before, no governing, , there was no way to raise money if there was a incipient panic. , there was no way really easily to get money from. The Midwest say to the east coast or the far west. there, weren’t [00:23:00] the things that we take for granted right now about how money works and how credit works.

[00:23:05] it was an economic system that was designed for the pre-Civil war, agrarian economy. And. The kind of major industrial power that the us was becoming. , Morgan had grown up watching the bank of England, try to keep the British economy on track. I mean, nobody really can keep an economy on track, but there are things that a smart central bankers can do.

[00:23:28] Obviously we see the fed trying to do that now in, , very different situation, but a definite economic crisis that we’re in. on the other side, were people like Alexander Hamilton who were trying to establish the economic and industrial, strength of the United States. And very much thought we needed a kind of national banking system that could coordinate among the states and the regions.

[00:23:55] And, he didn’t exactly foresee the fed, but Morgan sort of [00:24:00] stepped into that role of trying. I mean, somebody said he could, , sort of feel an oncoming panic, , cuz he was watching, paying very close attention to the markets and the currency supply and would try to shore up, , resources ahead of what he thought was coming.

[00:24:17] They always refer to it as storms a squall is coming or hurricane is on the way. and he would try. Gather under his control and that of other bankers enough resources to be able to supply money where it was needed in one of these terrible crises. Again, he wasn’t always successful at it, but sometimes he was, , there was a lot of controversy in the country during the last.

[00:24:42] Fourth quarter of the century about whether we should be on the gold standard as the rest of the world was, or have paper currency, which was easier. It meant money was cheaper, because you could just print it. But it also meant that other countries on whom the us was [00:25:00] dependent for the kind of money we needed to build the railroads.

[00:25:03] And then later these industrial corporations, investors abroad were reluctant to trust. Send their money, 3000 miles across the Atlantic, without some guarantee that it was gonna be safe which partly meant not devalued paper currency, brings on inflation and devalues the, asset that you’ve invested.

[00:25:23] So the fight was definitely on between. The industrial interests and the bankers and the farmers, for instance, who constantly farmers have to borrow money ahead of, , being able to harvest their crops. And they, can’t pay back until they’ve , been through the harvest. so as money.

[00:25:45] Getting more expensive if you’re on the gold standard, for instance, and the value of the dollar is either steady or, , going up, it means you borrow money when it’s worth. A dollar. And when you have to pay it back, it’s worth a dollar 50 it’s gone [00:26:00] up in value. So that fight has really been at the center of,, of American politics all along, whether you’re a borrower and need that money to be available and relatively inexpensive or a lender.

[00:26:15] In which case you want your investment, , your assets to retain their value. And that’s where. Morgan was absolutely on the side of Hamilton and the value retainers because he was representing Europeans who had millions of dollars invested in the growing us economy. And every time there was one of these panics and crashes, the investors would pull their money out and not send it back again until.

[00:26:41] A fair amount of time had gone by. And of course, the withdrawal of funds from those financial arteries made the panics and the crashes much worse. .

[00:26:49] So you mentioned that JP Morgan was central to the creation of key, , us corporations, us steel Edison, general electric, as well as the American [00:27:00] railroad empire.

[00:27:01] And all of this really helped propel the economic ascent of the United. States in the late 19th century, but let’s talk a little bit more about this, about how Morgan accumulated all of this financial power, the ways in which he leveraged trust in his reputation to draw in that European capital that you mentioned into these American businesses and industries.

[00:27:22] Jean: Yes. well, as I said before, he was working very closely with his father who was an American merchant banker in London. That’s the same, that’s what we mean by investment banker, but they called it merchant banker and they were together trying to raise this capital for the American marketplace, Was so wild and wooly because there were so many profit, there was so much money to be made on railroads and it invited speculators and gamblers and all kinds of people who were, , just out to make a buck. And didn’t really care about the consequences. The Morgans [00:28:00] were very careful about which railroad companies.

[00:28:04] Recommended to their clients and invested in, and they took what they called moral responsibility for the railroads that they were handling. And, you know, you could scoff at that now, but really what that meant was financial responsibility. So that if. One of the railroads, for which Morgan had sold bonds to European, especially the English.

[00:28:27] If one of those railroads got into trouble with bad management or a bankruptcy Morgan in New York would fire the managers, appoint new people whom he trusted to run the railroad. Or reorganize the finances and watch over it for sometimes 10, 15, 20 years, not just him personally, but he and his partners until it began to, operate smoothly and become a strong company that did then , repay the [00:29:00] investors, the interest they were owed. And then if they needed to get their money out, they could get out money. That was what they had put in rather than less. , because these bankruptcies totally wrecked the value of people’s investments and of the whole economy.

[00:29:15] Again, cuz it was so decentralized and, it was like setting a match to, dry Tinder when one of these things happened and they happened every 15 or 20 years. So Morgan was trying to prevent them. He was trying to, find good companies for his investors and then stay with them to, , make sure they operated successfully and profitably.

[00:29:38] And in that way, he and his father, but he was the one in America, earned the trust of investors on both sides of the Atlantic. And that was an absolutely invaluable asset because, especially in this, wildly competitive uncertain marketplace, having a bank, and a banker who you knew was [00:30:00] gonna be good for his word and who was gonna do everything in his power to sustain the value of your investment.

[00:30:06] obviously encouraged more people to bank with him and to send their money to the us. So they were acting as a kind of funnel from Europe to the American. Burgeoning, but very unsteady economy.

[00:30:21] GR: You mentioned that JP Morgan is a controversial figure. And as a result, mm-hmm, , , he found himself in popular cartoons, as well as being the model of a four character in a James, actually a Henry James novel.

[00:30:33] So can you talk about how he was celebrated as well as vilify, like, and tell us a bit more about his public disputes with Theodore Roosevelt and other progressive era figure. Regarding business trust of monopolies?

[00:30:46] Jean: yes, he was actually a character in many novels, certainly Henry James one. He’s a, character in EL Doctorow’s

[00:30:52] Ragtime and in, DosPassos and, a sort of combination of the negative portrayals called [00:31:00] him a bull necked irascible man with fierce intolerant eyes. , so he just close enough to suggest the psychopathology of his will. So that’s pretty scary picture. and Edward Steichen took his photograph in 1901 and that’s sort of what there were, he took two pictures, one sort of a normal one.

[00:31:21] And one Morgan was in, had settled into a certain position , and stend asked him to move. Morgan was sort of annoyed at this and got kind of ruffled. And the picture that Steon got of this slightly annoyed Morgan looks like an angry Hawk or a Falcon about to advance out of the frame. , his hand is on, the metal arm of his chair in, in the picture.

[00:31:44] It looks like a dagger that he’s about to start slashing with. So, and yes, the cartoons were, I mean, there’s a great cartoon of him. leaning over the globe over the Atlantic ocean with a huge magnet in. Hands and he’s [00:32:00] drawing into his magnet, all the art of the world. , so both in the world of art, which will get too soon.

[00:32:06] And in finance, he was seen as a great financial. and there were certainly people who celebrated him and mostly within the banking community, but also the international political community. When he stopped a panic, a major panic in 1907, that was. About to bring down well, a lot. he worked for two weeks straight, nonstop, not sleeping, calling all the major bankers of the country, into his library to shore up companies that were failing and put their own money on the line to.

[00:32:42] Stop this thing he succeeded and world political leaders just saluted his statesmanship with awe and crowds cheered as he made his way down wall street, for about a minute and then a minute after that, it terrified a nation of Democrats that one private citizen had that [00:33:00] much power. , and that panic of 1907, it was one of several that he.

[00:33:06] Managed or tried to stop, but it was the most dramatic and the most public, and probably the biggest and in the wake of that, the country really seemed to decide that that much power could not reside in the hands of one man. And it led to the formation of a national monetary commission and ultimately to the founding of the federal reserve, which came in, which.

[00:33:28] Began to operate in 1913, just a few months after Morgan died, just as the first national bank, the second called the second national bank, but had been dismantled just a year before he was born. So it really did span his lifetime, that there was no such, , function in the American government. Roosevelt came into office, threatening to bust up the trusts.

[00:33:53] And it wasn’t only Morgan’s trusts that were, , terrifying and antagonizing people. [00:34:00] Standard oil was a major villain on the horizon, according to populists and progressives. And, even the railroad trusts were considered, , to be. Serving the railroad company owners and that special deals were being made with shippers, like Rockefeller for oil, because he could control so much of what was being sent, that the railroads were giving him rebates, on the rates, they charged him, whereas just ordinary farmers trying to get corn from Iowa to.

[00:34:33] New York, , had to pay what seemed like exorbitant rates. So it seemed to a lot of America that the country was in the hands of these blood, thirsty bankers and monopolizes, and that big trusts, which was another name for monopolies and combinations and conglomerates that they had too much power.

[00:34:55] They were running the country entirely in their own interests. And it. [00:35:00] Not okay. there was a huge opposition to it. So Roosevelt came into office. Swearing that he was gonna do something about that. And one of the first things he did was, , take action against one of Morgan’s railroad trusts, the Northern Pacific, which there’s, it’s too complicated to go into now, but that had been put together in an effort to stop a previous panic.

[00:35:22] and Morgan was stunned because he had up until that point more or less had the cooperation of political leaders who agreed. At least quietly that he was working in the interests of the growing us economy and were not out to try to mess with him. , but Roosevelt, , did bring this suit against the Northern securities company and it was, , dissolved and, , that was a huge deal and setback in some ways for Morgan, but, , Roosevelt quietly continued to deal with Morgan [00:36:00] on many other fronts.

[00:36:01] there was a minor strike in 1902 and because Morgan had influence with the minors and the railroads Roosevelt asked Morgan to be the negotiator between the mine owners and the railroad owners. , , And try to make peace, which they ultimately did. So it was a very complicated picture.

[00:36:19] but the trust and monopolies were really hated and feared with very good reason. I’m not trying to justify them. I mean, I sort of had to see it from Morgan’s point of view in order to write this book and understand his life. But it’s very clear why so many people resented them and were terrified of.

[00:36:40] GR: you mentioned art and we know that he was a very, at one point, one of the world’s most were down art collectors. Um, mm-hmm some of this, of course wasn’t done by himself. There’s someone, Belle DeCosta Greene who was librarian and art collector and director of, Morgan library. Who was she? And [00:37:00] what role did she play in helping him accumulate art and become a philanthropist in the field?

[00:37:05] Of art.

[00:37:05] Jean: she is a completely fascinating character and I will tell you about her in a minute, but she wasn’t directing his, he was collecting on his own before she became the librarian and it was really his energy and impetus and, Taste and decisions that were governing what he was collecting.

[00:37:26] He had a nephew, in Princeton named Spencer Morgan, who had been his guide early on to rare books and an illuminated manuscript. And it was actually that man who recommended bell green to, Morgan, when she was. Clerk at the Princeton university library and a complete unknown, and because he trusted genius and he was always looking for the best person to do a job.

[00:37:51] he hired her, with nothing like a resume or a recommendation letter from someone else except his nephew genius. Bell was an extremely [00:38:00] important person in his life and in his library’s operations, but it was Morgan who was he had been collecting for years before she came on staff.

[00:38:10] He was collecting an enormous number of fields. And, she helped him, but I wouldn’t say it was her leadership. It was like his leadership and she was assisting him. She’s an extraordinary person. She said her name was Belle DeCosta Greene, that she had grown up in the south. Her mother was a music teacher and her ancestry was Portuguese.

[00:38:32] And that’s where the Da Costa name came from. She was quite mysterious about her background. I tried very hard to trace what she said about her. for bears. And none of it checked out. I actually hired a genealogy in Virginia to look them up and , there was nothing there turns out this is a very long story, but it turns out that she was the daughter of the first black man to graduate from Harvard.

[00:38:59] His name was [00:39:00] Richard Theodore Greener, and her mother was also Black, light skinned and, she was born in Washington and the family moved around a lot. They ended up in New York after the Civil War first in South Carolina, where her father was working for the university library. And then, He was in New York.

[00:39:26] He was secretary of the US Grant monument. At some point, the family split up and Belle and her mother and her siblings took the name DeCosta to explain their exotic appearance. when you see pictures of her, now you can see, she certainly looks possibly Portuguese, possibly. Well, it’s hard to tell, but, they weren’t dark, but they were definitely, when you look at the pictures, you can see what there is to see, but she passed for white the rest of her life.

[00:39:59] [00:40:00] Certainly a few people must have known there was some gossip, but she took on with Morgan’s patronage, a huge role at his library as. Sometimes she would go off to Europe as representing him at auctions and asking him how much she could bid and she’d go higher than anybody else could. And walk off with the best items at these auctions.

[00:40:23] And, , she. Became his, a confidant of his in many ways they would both stay at the library late and he would confide in her and talk to her. He had many women in his life and his marriage was not happy and there were other women and she, at least in her account would sort of keep them from running into each other and, , send gifts to one or the other.

[00:40:47] So she. A remarkable person. She was brilliant. And she was indeed an art collector on her own. And she was, The librarian with him at what was then called Mr. [00:41:00] Morgan’s library. And then he died in 1913 and she stayed on after that to work with his son, JP Morgan, Jr. Who continued to collect and of course kept her on and, , In 1924, the son who was called Jack gave the library with its collection, then an endowment to New York city.

[00:41:20] So at that point, Belle became the first director, official director of the Morgan library, what was called the Pierpont Morgan Library. And she stayed in that position, I believe until 1948, not sure what year she retired and she died not long after that, but she had love affairs. Many of the important men in the art world, including Bernard Berenson, to whom she wrote fantastic gossip.

[00:41:45] Honest irreverent, funny, witty letters. , they’re all at his Villa in Italy II. The Morgan library now has a big project to, , transcribe and digitize those letters. And the [00:42:00] library’s gonna have a big exhibition about bell and her. Whole story on the hundredth anniversary of the library being given to New York city.

[00:42:08] So that’s just a sketch of her. There’s lots more to say, but that’s, , in the time we have what I can tell you.

[00:42:16] GR: No, that was absolutely fabulous. In fact, I was looking at her picture online during the discussion and, , I can definitely see what you mean.

[00:42:24] Jean: Let me just have a footnote to that, which is that nobody expected to see a black woman in that position.

[00:42:30] so it wasn’t as hard as we might think to keep that secret, but sorry, just a PS. Oh

[00:42:37] GR: no, no problem. Well, since you have focused a great deal on your book, which is why we’ve invited you to the show, feel free to read a paragraph that you think we would like to.

[00:42:47] Jean: Okay. Morgan was a very hard man to know, not just for me, but for the people in his life.

[00:42:54] he was not articulate or introspective. I’m not reading it. I’m just giving you a little prey. [00:43:00] And, Henry Adams said of theater Roosevelt that he was pure act and that was true of Morgan as well. So when Morgan died, one of his British partners who really did get to know him very well. To his fiance, a letter that I’m gonna read to you, he wrote that, for Morgan, more than for most people, a sick, old age, would’ve been full of misery. His life had been one of fight. He had no taste for reading or gifts of conversation and the life of inactivity bittered by illness. Would’ve been a living torture to himself and his friends. It is rare that the obituary notices of an American financier can be written without unpleasant criticisms of methods and intentions.

[00:43:43] And yet though, he was almost brutally independent of the press. The notices of JPM were uniformly pleasant. He filled a great place. And on two occasions, especially saved America from disaster. It may be that his work was finished and that no occasion will again, arise for [00:44:00] treatment of a crisis in the peculiarly masterful manner that he adopted, probably that is for the general good.

[00:44:07] The one man power may bring evils unless the agent is entirely single minded and with human nature, as it is ambition, jeopardizes, single mindedness. If Benzel meant that self-interest jeopardized objectivity, he echoed the concerns of the American editorialists who praised Morgan’s testimony at a committee hearing just before he died with the reservation.

[00:44:31] It will never do to say that unchecked power is a good thing because it is in the hands of good. Assuming moral responsibility for the growth of the strongest economy in the modern world. Morgan had earned the trust of leading international financeers and statesmen his breast exterior, notwithstanding he did care.

[00:44:50] About what people thought of him, but he neither looked for popular favor nor altered course in the face of opposition. He could no more give up what he had been doing all his life [00:45:00] than he could explain it. As he said, he thought it was the thing to do.

[00:45:05] GR: Thank you so much for joining us today, we look forward to future conversations and I’m sure our listeners will really take a lot from this conversation.

[00:45:15] Jean: Thank you. . Thank you.[00:46:00] [00:47:00]

[00:47:49] So the tweet of the week, Gerard comes from education week on July 11th. They wrote virtual reality in the classroom may sound complicated to [00:48:00] master expensive, to implement, and generally more trouble than it’s worth. But those are misconceptions said to teachers who regularly use the technology in their classrooms and then education week linked to one of their ed week articles on virtual reality.

[00:48:15] And I thought this was really exciting because, there’s so much education innovation coming through the virtual reality space, a lot of innovative education startups that are working on VR technology. So, great to see some teachers recognizing the value and incorporating VR into their C.

[00:48:33] GR: In fact, I had an opportunity to travel to Minneapolis a few weeks ago, to participate in a conference, , supported by, , generator, which is in, , , a venture capital fund that’s seeding money into startups.

[00:48:47] And there were five, founders. Who made a, pitch, they already had won money, but it made a pitch to those of us at dinner, about what they were doing. , VR was part of the conversation, but just the use of [00:49:00] technology to help teachers. In fact, a couple of the founders, our former teachers who said, I wish I would’ve had this when I was in the classroom.

[00:49:06] So always glad hear tweets of the week, , they focus on not only VR, but stem or I should say steam in.

[00:49:14] Yeah, and I think I will be joining you again next week for our guest, , on the podcast next week. You’re gonna tell us a little bit about who

[00:49:20] Jean: she

[00:49:21] GR: is. Yes. Bernita Bradley is the founder of Engaged Detroit.

[00:49:27] It’s a parent driven urban school reform advocacy network. Uh, it will be great to talk to her because she has a very organic. , feel for what parent driven urban reform looks like, , in the city of Detroit, which has had a number of educational fiscal and social challenges, , for more than 50 years.

[00:49:47] So to hear from someone who said, Hey, rather than talk about the problem, I have a solution. And so do a lot of other parents in my city. So, as an advocate and someone who, one point was the president of the black Alliance of educational options, [00:50:00] we had a chapter in Detroit, which was very important chapter to us, really look forward to hearing from Bonita.

[00:50:07] Absolutely. And, you know, really working on kind of schooling, alternatives and homeschool co-ops and all kinds of interesting learning models in Detroit. So it’d be great to hear more

[00:50:17] GR: from her. Well, Kerry, thank you so much again for joining me as a cohot for today’s show. And I look forward to joining you next week.

[00:50:24] Same I’m really looking forward to next week’s conversation. Gerard

[00:50:27] GR: take care.[00:51:00]

Recent Episodes

UK’s Dr. Paula Byrne on Jane Austen’s 250th Anniversary

EdChoice’s Robert Enlow on School Choice

Frontier Institute’s Trish Schreiber on School Choice & Charter Schools in Montana

UK Oxford’s Robin Lane Fox on Homer & The Iliad

Director/Actor Samuel Lee Fudge on Marcus Garvey & Pan-Africanism

Cornell’s Margaret Washington on Sojourner Truth, Abolitionism, & Women’s Rights

UK Oxford & ASU’s Sir Jonathan Bate on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet & Love

Steven Wilson on The Lost Decade: Returning to the Fight for Better Schools in America

U-Pitt.’s Marcus Rediker on Amistad Slave Rebellion & Black History Month

Notre Dame Law Assoc. Dean Nicole Stelle Garnett on Catholic Schools & School Choice

Alexandra Popoff on Vasily Grossman & Holocaust Remembrance