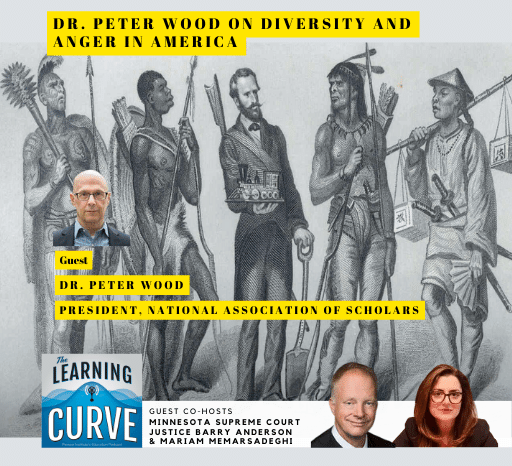

Dr. Peter Wood on Diversity and Anger in America

/in Featured, Podcast /by Editorial StaffRead a transcript

Mariam Memarsadeghi: Welcome to The Learning Curve podcast. I am Miriam Memarsadeghi, guest co-hosting with my good friend, Judge Barry Anderson, justice on the Minnesota Supreme Court. We know each other from judging an annual competition on high school students’ knowledge of the U. S. Constitution, the We the People competition put on by the Center for Civic Education. And uh, I’ve gotten to know Barry through that excellent experience and really treasure him. Barry, could you introduce yourself some more?

[00:00:57] Barry Anderson: Well, thanks very much for those kind words. I have to say, Mariam, anytime I’m talking to you, I’m thinking, shouldn’t we be talking about the Declaration of Independence, or George Washington, or the drafting of the Constitution in 1780s? Well, I guess we won’t talk about that here. We’ll talk about other things. I’m privileged to be a part of this Learning Curve podcast. I’m delighted to have been asked to participate as your co-host. And I’m very much looking forward to discussing some of the education issues and other matters that frequently come up in the course of this excellent production. I’m just going to say that Minnesota has its own experiences in education. Maybe I’ll talk a little bit about that as we go along here.

[00:01:35] Mariam: Wonderful. Barry, what’s caught your eye in the news this week?

[00:01:39] Barry: So, we were kind of looking at potential articles to look at, and I ran across a piece by Mark Bauerlein in First Things dealing with Catholic education, and it’s pretty interesting. He entitled it Catholic Education Is Taking Off, and the piece itself is not data driven. It’s more a narrative account of visit that he made to the Institute for Catholic Liberal Education at its annual conference at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. And he talks a little bit about what he experienced there, mostly, increasing numbers of students attending Catholic education throughout the country and some of the experiences and the general superiority in his view of Catholic liberal education over, say, secular education.

[00:02:24] Barry: I’m going to leave the theological things for other people to discuss. As a Lutheran, I’m not going to criticize Mark’s Catholic view of things, but I think he is in this article, I think he does a great job of defending what I would call liberal, small-l education, the so-called liberal arts, and we know they’ve taken a hit and he sees Catholic education as real alternative to public education from that perspective.

[00:02:50] Barry: I just want to note that he does talk a little bit about increasing attendance and that’s true. I think it is important to keep in mind that public education in the United States educates something on the order of 50 million students, Catholic education, a little bit less than 2 million at the K-12 levels. So, there’s a lot here I think is really helpful to understand about some of the success, but it’s also just a small piece of a very large puzzle.

[00:03:16] Mariam: That’s fascinating. It’ll be important to see how private school education provides an alternative as we move forward. If public schools are going to continue to really fail Americans in that way. I mean, the liberal arts, an understanding of history, the classics, civic education — are things that we need to have back robustly, and maybe private schools, charter schools are going to present alternatives as we move forward and hopefully inspire the regular public school system in different states to adopt those.

[00:03:52] Mariam: I know that recently we talked about how New Hampshire’s is stepping it up in this regard. My story, Barry is from Axios. They cover a Gallup poll that shows that the share of young adults who say they are extremely proud to be American has taken a nosedive. I found this to be very disconcerting as an immigrant to the United States, who really takes a lot of pride in what America is about. I’m originally from Iran, came to the United States during the revolution in 1979. I see this as a problem that’s part and parcel of a larger problem of Americans being divided, not having a common sense of identity, not having a common sense of media and education. And I think a big question in my mind as I read the numbers and what — another number uh, you know, in addition to that the young are not proud of their country — is that 60% of Republicans overall Republicans, not just young Republicans, but Republicans in the United States, 60% of them are extremely proud versus only 29% of Americans nationwide. So roughly speaking for every Democrat that is very proud of her or his country, there are two Republicans who are. I thought to myself, how is that? are there things that justify it? What’s to blame? And I found myself coming back to education, that there’s a certain — well, at the very best, a lack of awareness of how America compares to the rest of the world.

[00:05:33] Mariam: Why is American exceptionalism a valid thing to teach? Not just that, but at the extreme end, I think there’s a certain self-loathing that is being taught in our system, not just at the university level, but K through 12, too. So, really caught my eye and was not reason to be happy. I think that we need to be teaching more about what makes this country great, but also how we compare to countries in the world, particularly, our big rivals — China, totalitarian regime Russia, totalitarian regime, Iran, a totalitarian regime, and why it’s important to value what we have in order to safeguard our democracy.

[00:06:19] Barry: I want to pass along two things as I’m listening to you talk about that piece. One ties back to the point Mark Bauerlein was making in his article about the value of a liberal arts education, which of course includes an emphasis on history, political philosophy, various types of government, things of that sort. And I think that is something that is clearly needs greater emphasis in our education system. And, like I said, I saw that echo there in the piece that Mark wrote. But then I also want to note that some of this is just a function of students not understanding, not knowing that history.

[00:06:52] Barry: I don’t need to tell an immigrant from a totalitarian regime this, but I can tell you, for example, I represented many years ago in my private law practice, I represented individuals who came from Eastern European totalitarian regimes. And they had no illusions about whatever problems Americans might have with their government or, how things have developed with respect to particular issues. They clearly saw the superiority of democratic and republican forms of government compared to their life experiences.

I don’t think students today maybe get as full an exposure as they should to some of those life stories that other people have had. So, that’s my, my two cents worth on your poll. It’s, I agree, extremely disturbing.

[00:07:36] Mariam: Yeah, yeah. So, after the break, we’ll be speaking with Dr. Peter Wood. Dr. Peter Wood has served as president of the National Association of Scholars, and he is the author of Diversity: The Invention of a Concept, published in 2003, and A Bee in the Mouth, Anger in America Now, published in 2007.

[00:08:14] Mariam: Dr. Peter Wood has served as President of the National Association of Scholars, the NAS, since 2009. He was Associate Professor of Anthropology at Boston University, where he also served as the President’s chief of staff and served as Provost of the King’s College in New York City. Dr. Wood is the author of Wrath, America Enraged (2021) and 1620: A Critical Response to the 1619 Project (2020). He is also the author of several other books about American culture, including Diversity: The Invention of a Concept (2003) and A Bee in the Mouth, Anger in America Now (2007), as well as Diversity Rules (2020). In 2019, he received the Jean Kirkpatrick Prize for contributions to academic freedom. Dr. Wood is editor in chief of NAS’s quarterly Academic Questions and writes frequently for Spectator World, The New Criterion, The Claremont Review of Books, American Greatness, and other publications He received a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Rochester. Dr. Peter Wood, it’s a pleasure to be speaking with you.

[00:09:34] Peter Wood: Well, my delight to be here. Thank you.

[00:09:37] Mariam: Your 2003 book, Diversity: The Invention of a Concept, is among the most thorough and farsighted examinations of contemporary diversity, a term that’s become the water in the aquarium of American life. Would you share with our listeners how you decided to write this book? As well as what diversity is and how it’s come to dominate our culture in recent decades?

[00:10:00] Peter: Well, I came to write the book because I’d written a short article about diversity on National Review Online, which eventuated in my being invited by Ward Connerly, a major figure in the fight against racial preferences, to come out and visit with him and some of his friends at the Reagan Library.

[00:10:23] Peter: And at the library, I met the then editor of Encounter Books. Peter Collier, who suggested that I turn my very short article into a book. So, this is a book that originated with the publisher saying, this is a good idea. Give it a try. And I wasn’t sure I wanted to, but books don’t lend that easily so often, so I gave it a try. The story from there is one of spending several years deep into the historical research of where this concept of diversity came from. The very short answer to that is that it came from the 1978 decision of the Supreme Court in the case of Bakke v. the Regents of the University of California.

[00:11:10] Peter: Of course, the word diversity doesn’t come from there. It’s much older in English, but it, gained that occasion a kind of legal force that eventually turned it into the cultural icon that we know today. That’s a fairly long story, but to keep the answer brief, higher education adopted diversity as a way to justify what the American people did not want, which was racial preferences in higher education. But after about 10 years of clogging the idea of diversity as a brand new, previously undiscovered constitutional right, the American people began to take it in and believe it.

[00:11:54] The corporate world adopted it. Many churches adopted it. It became a notion that we could overcome all of America’s racial discontents by embracing this shiny new toy of diversity. It didn’t sit well, even with a lot of advocates of racial justice because it seemed to imply that the only reason to have blacks and other minorities around was to make sure that there was a lively intellectual discussion going on among the whites nonetheless, diversity eventually became kind of magic word that is ready to enter into any conversation to satisfy the disagreements that Americans do have over what are the best ways to overcome the nation’s history of racial injustice.

[00:12:45] Miriam: Yes, and in Diversity: The Invention of a Concept, you open with a discussion of MLK’s image of human unity as a single garment of destiny, as he says. Could you talk about MLK’s use of this metaphor of a single garment of destiny and how it connected his civil rights work with older, even ancient biblical understandings of the oneness of human nature, liberty and equality, and the liberal arts tradition?

[00:13:15] Peter: The metaphor, I think, was a very powerful one, and it suggested this need to look upon all of humanity as possessed of a single set of qualities that make us human and that the other claims that we make upon one another for the rights or our grievances have to be rooted in an understanding that beneath all of that is a single unified human nature.

[00:13:41] Peter: That’s something that I think is certainly deeply implied in the Hebrew tradition, as well as Christianity. MLK himself, of course, was a student of theology, and he did not take up this image lightly. It, for him, bore the full weight of his grasp of what human nature is, which is to say that we’re not simply driven by our appetites and urges and desire to dominate, but by a recognition in one another of some element of godliness, that quality that says that you need to respect human dignity as a quality that inheres in everybody, no matter how lowly their station might be.

[00:14:27] Peter: The liberal arts tradition teaches that as well. We people who uphold the liberal arts tradition view it as something that opens the doors of wisdom and education to anybody who strives to go through those doors. It’s not that the knowledge is instantly available. It always requires a deep commitment of hard work to gain the knowledge, but it is within human nature that we are educatable, that we can learn from our mistakes, that we can move towards common understandings, not just the sorts of understandings that are limited by social identity or by one’s reference group. So, I think MLK had it right. And it’s unfortunate that that image of human unity is sacrificed on the altar of diversity, which says, well, no, we don’t have all that much in common. Each of our groups has got its own traditions that need to be not just respected but held up as more important than our commonalities.

[00:15:29] Mariam: And it’s essentializing. It reduces every race. to a particular way of thinking or worldview rather than that every individual, every human is equal. And as an extension of that equality, they’re capable of great ideas, not so great ideas and, differences of opinion within their own racial identity.

[00:15:53] Peter: Well, we owe it to Justice Powell that this mischievous new form of diversity got started, but his view was that the identity group to which one belonged could be mapped onto the ideas that belonged to that group. So, individuality had no part of it. It was all about groupness, not individual identity.

[00:16:19] Mariam: It’s dangerous thinking. I mean, coming from country where people reduced to their sex and gender and racial and ethnic and religious identity. I’m talking about Iran, of course, the extreme end, but if you follow that way of thinking to its end, it denies freedom and it denies justice, in fact, rather than fostering it.

[00:16:42] Mariam: So, in your book you say that the new movement, this focus on diversity, the new movement is something different, different from MLK’s vision, and in some ways a repudiation of the older attempts to find a oneness in our manyness. Diversity in its new form tends to elevate manyness for its own sake. So, if I can just add here, it’s, sort of, the opposite of e pluribus unum, from many we are one. Would you talk about and compare old and new forms of diversity and explain how new diversity became an ideology of victimhood, as well as rationale for wide-ranging lawmaking, advertising, influence on education.

[00:17:28] Peter: Sure. Well, let me back up a little bit. The word diversity in English originally meant “a bad condition.” When a kingdom or a nation was in a state of diversity, in this older usage of the word, it meant that things were coming apart, that people were divided against one another, and that social distress would be the result. Diversity began to gain something of a positive meaning with Darwin, because he found in nature the diversity of the offspring of each generation provided opportunities for adaptation and growth. And that more positive sense of diversity, I think, found its way into kind of common usage by the early 20th century so that we could begin to look upon the great range of ideas at any one time as something of value because it meant that we could debate those ideas, discuss them, put them forward and see where the evidence led us in favor or against one idea or another. Learning to accommodate people who are different from yourself was a positive aspect of diversity, but diversity was therefore something that we learned to tolerate, not something to celebrate. That is, we could make of our differences a path towards common understanding.

[00:18:48] Peter: The new sense of diversity, and in that book, which I wrote more than 20 years ago at this point, so it’s not so new after all, but the then-new sense of diversity was that this was in itself a constructive thing. That we should celebrate diversity that became the key verb always attached to it. Celebrate diversity meant that the differences were not to be overcome through. Discussion or mediation of some sort they were to be preserved and the more different you were, the more there was to celebrate new diversity is itself divisive. It takes people who might in fact have far more in common than they have in difference between them and say, well, forget the commonalities, the differences are what matter. If you’re African American background, focus on that, not on the fact that you’re American. If you’re Iranian American, don’t play that up, play up the fact that you are Iranian. And we go down this path of seizing upon every sub-commonality to make of it, as you just said, something essential, so important that it overrides all the claims that we might have on one another’s basic humanity.

[00:20:14] Mariam: Yeah, and it’s a national security risk, really, because our enemies — I’m thinking China, you know, primarily, but really all those anti-American regimes that are anti-freedom — they are certainly not fostering these ideas, quite the opposite. They’re emphasizing unity and, you know, of course, that’s not the model either that we’re aspiring to, a forced unity. But within the American experience itself, we’ve lost that unity that is based on pluralism and freedom and replaced it with something that, you know, many people from within the left even are pointing to as a kind of authoritarianism or even totalitarianism in universities and indoctrination.

[00:21:01] Mariam: I know that I was in a PhD program at the University of Massachusetts, in 1994 to 1997. And I — there wasn’t as much awareness back then of what was happening, but it certainly felt like in order to have a career in political theory at that time, I had to accept a set of values and ideas, and not just compete in terms of knowledge and understanding of the canon of political thought.

[00:21:30] Mariam: So, you’ve described the, U. S. Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell as the legal founding father of new diversity with his 1978 stand-alone opinion in the SCOTUS case, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, which upheld affirmative action in college admissions policymaking. Given the recent SCOTUS decision on affirmative action, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard/UNC just this year, 2023, would you briefly walk us through Bakke, Grutter v. Bollinger of 2003 and how the current court arrived at its recent ruling on college admissions and diversity?

[00:22:14] Peter: Okay, well, that’s a big territory, but I’ll try to give a concise answer. The court in Bakke split three ways. There were four justices who wanted to invoke the Civil Rights Act and say that Bakke had to be admitted, that the University of California Davis Medical School, which had rejected him in favor of several minority candidates, had acted wrongly. And by the statute, he should be admitted. There were four other justices who were just all in with racial preferences in college admissions, and they wanted the California position to prevail. And then there was the ninth Justice Powell, who ultimately decided that Bakke should be admitted, so he gave the four conservative justices the majority they needed to see Bakke admitted, but he then added to his opinion this rather lengthy discussion saying that he would have decided the other way if University of California had justified its use of racial preferences, by saying that they enhanced classroom diversity, that putting more people of different skin color in the same medical school classroom was going to produce better doctors.

[00:23:33] Peter: None of the other eight justices, neither the four liberals nor the four conservatives, agreed with him, but his opinion prevailed. The remarks he made about diversity fell into a category called Supreme Court dicta, that is, things said that don’t have the rule of law behind them. Even though it wasn’t a binding legal decision, it did launch the career of the concept of diversity.

[00:23:59] Peter: The next really major landmark in that career was the 2003 decision the Supreme Court made in the case of Grutter and Gratz versus the University of Michigan, versus Bollinger, who was then president of Michigan. And in that case, the prevailing opinion came from Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who finally turned Lewis Powell’s somewhat suspect category of diversity into a real legal standard. The majority of the court, that is O’Connor siding with the four liberal justices, came up with this idea that, at least for the next 25 years, she said in 2003, we will permit colleges and universities to pursue racial preferences with some qualifications as a way of advancing diversity in higher education.

[00:24:55] Peter: The qualifications are sort of interesting. That is, the colleges were allowed to say they were justifying racial preferences by recurrence to this idea of diversity, but they couldn’t just admit people straight out because of race. They had to disguise it by saying that they were seeking something like a critical mass of minority candidates. They were going to do holistic assessment of each individual so that race wouldn’t be the only factor, but it would be one factor considered among many. Since 2003, O’Connor’s opinion has stood up. There were two important legal challenges before the current one of the two Fisher cases from Texas. And in both those instances, the Supreme Court continued to back down and say, okay, we’ll allow this violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act to continue a while longer. What has just happened with the Roberts decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and North Carolina, University of North Carolina, has been that Supreme Court has pulled the rug out from underneath that old pretext.

[00:26:08] Peter: Diversity is now no longer acceptable as a reason to ignore the American Constitution’s guarantee of due process and equal rights for everyone. This, of course, has sent off huge alarms in American higher education, which is so wrapped up and committed to its diversity doctrine that they are searching for ways to defy the Supreme Court’s order. And that’s exactly where we are today.

[00:26:36] Barry: Dr. Wood, you wrote two books 20 years ago, almost 20 years ago. We’ve been talking about one of them dealing with diversity that suddenly is relevant again. It’s been relevant all along, but really relevant now. And you wrote a second book in 2007, A Bee in the Mouth: Anger in America Now, which has unfortunately continued to be relevant. And I think like your diversity book. is increasingly relevant. That book was about the culture of anger that today seems to be very much prevalent in American life, music, and politics. I’m wondering if you could compare that culture of anger that we have today with an older view of the American character, the self-control of George Washington, and compare that to what you’ve called the new anger.

[00:27:22] Peter: Right, well, the simple contrast on which the book was built was the idea that once upon a time — not all that long ago — Americans put a very high value on self-control. The angry person was viewed as weak, as being in some sense contemptible. The person who inveterately gave in to anger was viewed as kind of crazy. But it was certainly well recognized that people did get angry and sometimes for good reason. The question was always what do you do with anger when it comes into your life? Now we have a national model for that, largely forgotten at this point, in George Washington, who, we look on the dollar bill or on his well-known portraits and see this man of very dignified and stately mien, but George Washington in his own life was known as someone who had a terrible temper. He could lash out at people and get quite scary. He was a very large man as well. So, his anger was intimidating to other people. Early in his life, he realized he had a problem and would not have a public life if he didn’t master it. So, Washington set out by first writing rules for himself, kept a little book of his rules. He engaged in the kind of self-control that began to impress people as the sign of a man of real maturity and dignity.

[00:28:51] Peter: There are plenty of anecdotes about this. My favorite is that when Washington was getting ready to cross the Delaware on New Year’s Eve, that stormy, snowy night, he had sent a detachment of soldiers across the river before him to do some reconnoitering. But they were under strict orders not to engage the enemy, because Washington did not want to tip off the British or the Hessians, and as it happened, they disobeyed his orders and there was a light skirmish, but it was enough to tip off the enemy that something was happening. When they came back across the Delaware and Washington met them, he was livid with rage at what had happened and was about to explode at them. And we have witnesses to this: He turned on his heel, looked away for a moment, and then turned around again, and with complete self-control, dismissed the people who defied his orders and said, we’re going to go ahead with this. And it’s that sort of display of, OK, I’m not going to get anything by yelling at these people or allowing myself the pleasure of rage against their insubordination. I’m going to make the best of this circumstance by bringing them back on board with me and making sure that this operation works. That is the old anger and there are many portrayals of it in our literature on film on the way in which we have turned the corner on this is that something happened.

[00:30:29] Peter: I pinpointed as happening in the years just after World War II, where Americans began to gain a sense that being angry was kind of neat. It was powerful. Now think of this as, first of all, the importation into the United States of Freudian psychoanalysis, which bears, among other things, the idea that if you repress your anger, if you hold it back, you’re going see it return in the form of psychological neurosis. That idea began to gain some traction with the American public. One way to see that is that book of, I guess, really tremendous success of the 1950s Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, which depicts a very angry young boy wandering around New York City for a few days after he’s been kicked out of his prep school. We learn in the very last chapter of the book that he is talking to his psychoanalyst, that this whole thing of his rage against the world turns out to be part of his confession to the psychoanalyst who tells him basically, yeah, you’re good to go. On this turn towards revaluing anger as a positive emotion, also plays out with the oh, the importation after World War II of existentialism, this idea that to be authentic is the most important value, and that deep authenticity means finding what your really core emotions are and expressing those. So, we had an explosion into the arts and literature in the 1950s, not a period that we habitually think of as an angry decade, but it was catching on with the cultural trendsetters, the elites. And by the 1960s, it was completely out in the open. The new idea of what it means to be a mature person was that while you forget maturity, you’re going to express yourself.

[00:32:42] Peter: And when you express yourself, the part that needs most expressing is one’s discontent, the anger. So, we see new anger, as I call it, coming to the fore in the social movements of the day, in some aspects in the civil rights movement, certainly in feminism it was a call to rise up against the structures of oppression and be angry about it. But not just be angry, but to show your anger. So, the new anger is performative. It has a quality of, look at me, I’m angry, and because I’m angry, I’m powerful and you need to reckon with me. Anger becomes the psychological resource for those who want to change American society. Now. having pushed all those words out in answer to your question, let me add something you didn’t ask.

[00:33:33] Peter: My diversity book was quite a success, and it continues to be, and people find in the history that I wrote of the concept of diversity, something that really attracts attention. Bee in the Mouth: Anger in America Now did not do so well. I view it as my more intellectually creative work where I broke new ground on an important subject. But I ran into a wall that I didn’t expect, and which bears on this part of our conversation. The wall is that most Americans have a very hard time recognizing that their anger is in any way socially constructed, or that it’s anything but just how they feel. The ability to look at this and realize that at one point in our history that’s not how you felt and then at another point it was — there is a social change that takes place from a social ethic that says self-control is the most important thing to a different time when self-expression becomes the most important thing.

[00:34:41] Peter: That is so deeply taken for granted now among most Americans. That they have a hard time seeing that there could be anything new about being anger. They project their new value onto the past, which of course we. see all the time in the, in the bad history of today where we’re constantly treating people who lived in generations before us as though they were just like us and should know what we know.

[00:35:06] Barry: You know, I would say this, I would make this observation, Dr. Wood, about your point about the fact that Bee in the Mouth perhaps was not as successful as your diversity book. There are books and there are opinions. The business that I’m in that languish for long periods of time before they’re rediscovered, and the wisdom set forth therein becomes useful. So, we can hope that your book will be, rediscovered, and I suspect it will. I do want to touch on something that you mentioned in the course of talking about, the post-World War II era, and that was the culture you mentioned arts and music, you know, Plato talks about the, importance of education and music, and you have in your book, a chapter that deals with this. You talk about anger music. Maybe you could share some insights from that chapter about angry music, including rock and roll, punk rap, other things. This is not an area of specialty for me. I got tossed out of the seventh grade band, but uh, nonetheless. I think that you’re on to something here, and I think our listeners would like to hear something about that.

[00:36:10] Peter: Well, of course, since I wrote it a while ago, the references to the popular music are dated for sure, but I’ll start with a more general comment, which is that popular music teaches us how to feel. It’s not part of the school curriculum that way, but it’s part of the curriculum of life. When you go back and try to figure out, how did you learn to love, how did you learn to hate? A lot of that turns out to be from the lyrics and the music that those lyrics are embedded in that teach the heart, they begin to be the places where — outside what your parents or teachers may be teaching you — what you heard maybe on a transistor radio in the 1960s or a compact disc sometime later, and now your downloaded files, you’re hearing something that goes very deep into the soul. And popular singers have this mysterious capacity, as you point out — Plato is on to that — where we know that whatever we might teach by way of philosophical truth is going to be in competition with those heartfelt truths, and the people who master those, first of all, are, singers, the musicians.

[00:37:30] Peter: So, That, I think, is the essence of that chapter. I try to go through several genres of popular music. Maybe the more obvious ones are things like protest songs and some of those are very stirring but we have to ask, what is really going to happen to people who find the key to their life by listening to music that hits that moment when we become enraged, become concerned about — well, concern is far too weak a word — the sense of betrayal is a perennial theme of a lot of country music, for example. The sense of being treated as an outcast and therefore someone who can rage against the system is maybe one of the core themes of rock and roll. Rise of this kind of anger music and I certainly don’t want to say all popular music is angry.

[00:38:31] Peter: It is a major true line in our popular music for the last half century, and that contrasts that music with what came before. It’s hard to look back to what’s called the American songbook to find angry songs. You find sad songs, you find beautiful songs, but you don’t find songs in which the whole point is to engage in this structured rage against the way the world has mistreated me. That’s become our music. It reaches its, I think, apotheosis in — how’s that for a 10-dollar word for this conversation — in rap, I mean, we have a whole genre there where the basic underlying theme is one of rage against mistreatment, which may not be, and oftentimes is not racially defined, but this treatment that the poor person feels against the rich person, the wrong person feels against the one who’s transgressed against him and so on. So, out of music has come instruction that no school could ever control in how it is we should feel.

[00:39:44] Barry: You know, in your concluding chapter, Cooling Off, as well as your other writings, you’ve advised, requested, suggested, modeled writing in public discourse that’s dispassionate, witty not angry. I think it’d be useful, as we finish off our program today, if you could talk about some of the ways that Americans could reclaim a calmer, less wrath-filled culture and civic outlook. And do you have any words of hope any observations that maybe that process is beginning?

[00:40:15] Peter: Hmm. Well, you pose a difficult question, and you make me really mad! No, the answer to this surely lies, first of all, in seeking the kind of peace that we have or can have within our families. And I’m pretty sure that much of the discontent that characterizes our modern or postmodern condition arises from the fact that we are having so much trouble creating families that can transmit from one generation to the next some basic love of one another and of what’s good in the world. We take such pride in being enraged and being able to show our rage that kind of satisfactions that can come from a more temperate look upon the world are unavailable to most of us.

[00:41:13] Peter: So that’s first of all, a question of how do you provide people who have been distorted by their culture and by their opportunities in life, some path back on to a better sense of who they might become? Well, the traditional answers to that, I’m afraid, are still the only answers we really have. One turns to God, to religion. One looks to the high arts as places where the soul can be healed. And if you’re resistant to those things, as many people are, you have to have around you people who can model, who can actually show that a life devoted to these better angels is a life that is enviable, it’s worth having. So, we need to see people who in public life can show us what it looks like to be maybe unhappy with some social condition, but ready to find a path forward that does not involve explosions and examples of public rage.

[00:42:28] Peter: Now it’s a difficult time for those of us on the temporizing side, the side that says, let’s find something better in ourselves, because we have so few politicians or political leaders or public leaders anywhere who actually show us what that looks like. They’re there to be found and I’m not going to start calling out names, but I think we all can sense for the person who has achieved a certain level of inner peace and equanimity towards the world not in the form of giving up and complacency, but in the form of saying that I will meet the wrongs of this world with an attitude of forbearance where I can, tolerance where that’s necessary,. and constructive engagement when everything else fails. So, that’s a pretty abstract answer to your question, but I’m afraid it’s the best I can do.

[00:43:16] Barry: Well, thank you, Dr. Wood. I appreciate it and I thoroughly enjoyed your book and appreciate the time that we spent today discussing it. Could you share a paragraph for us?

[00:43:36] Peter: Sure. will read the opening of my most recent book, Wrath: American Enraged, which is a revisiting the topic of anger in America. So here goes. What is the difference between wrath and anger? How dare you ask? That’s anger. I will destroy you. That’s wrath. Wrath is more intense and usually more sustained than anger. That’s unacceptable, says the angry diner to the rude waiter. I will track down the names and locations of your family members and post them on the internet, says the wrathful political partisan. Some wrath, I believe, is justified. The popular will of Americans has been thwarted by a combination of careerist elites, progressive ideologues, and unprincipled press, and a business class more attuned to global opportunities than to domestic flourishing. Because traditional forms of political protest have been tourniqueted by mass arrest, censorship, and decisions by the law enforcement and the courts to stand aside, many Americans see themselves as having been denied a legitimate voice in their own governance. They are right in that judgment. It is the kind of judgment that turns anger into wrath.”

[00:44:54] Mariam: Thank you so much. Dr. Wood is a pleasure to be speaking with you today.

Peter: My pleasure entirely.

[00:45:30] Mariam: That was an engaging interview. Fascinating. Let me tell you about a tweet that I saw about how students or families rather are going to be spending significantly less this year on back-to-school supplies than they did last year. Deloitte has a back-to-school survey annually, and I saw that people will be projecting to spend 9% less than they did last year. And this caught my eye because prices are already very high. Uh, Inflation is high, and people are also spending less. So ultimately, students — particularly the poor students in America — are going to be having less as they go back to school. Parents are prioritizing supplies over clothes and devices. I thought that was good because maybe electronic devices aren’t serving our young people as much as we once thought that they would, but still concerning, particularly for the working poor who are already struggling to give the best to their families.

[00:46:40] Barry: You know, as I’m looking at that tweet, I would just say that for those of us of a certain age — and I’m in this group — who experienced the inflation of the late 70s and early 1980s, it really is an eye-opening experience. And we’re fortunate that The current inflation rates aren’t as great maybe there’s some sign that are ameliorating a little bit, but it is really a burden for families that work from paycheck to paycheck, and I think that sometimes is missed by our media coverage.

[00:47:10] Mariam: Exactly. Barry, I have enjoyed co-hosting this show with you so very much. Next time on The Learning Curve, we will be joined by Professor David Aboulafia. David Aboulafia is Professor Emeritus of Mediterranean History at Gonville and Keyes College, Cambridge University, and author of The Boundless Sea, A Human History of the Oceans. Hope you’ll join us for that one.

This week on The Learning Curve, guest cohosts Minnesota Supreme Court Justice Barry Anderson and Mariam Memarsadeghi interview Dr. Peter Wood, president of the National Association of Scholars. Dr. Wood discusses the invention of the modern concept of diversity and how it has replaced earlier understandings of human unity, liberty, and equality as exemplified by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s civil rights message of “a single garment of destiny.” He traces the history of U.S. Supreme Court rulings on the use of diversity in college admissions while also addressing how a culture of anger seems to pervade American life, including our music and politics. Dr. Wood concludes the interview with a reading from his latest book Wrath: America Enraged.

Stories of the Week:

Guest

Dr. Peter Wood has served as president of the National Association of Scholars (NAS) since 2009. He was associate professor of anthropology at Boston University, where he also served as the president’s chief of staff; and he served as provost of The King’s College (NYC). Dr. Wood is the author of Wrath: America Enraged (2021) and 1620: A Critical Response to the 1619 Project (2020). He is also the author of several other books about American culture, including Diversity: The Invention of a Concept (2003); A Bee in the Mouth: Anger in America Now (2007); and Diversity Rules (2020). In 2019, he received the Jeane Kirkpatrick Prize for contributions to academic freedom. Dr. Wood is editor-in-chief of NAS’s quarterly, Academic Questions, and writes frequently for Spectator World, The New Criterion, The Claremont Review of Books, American Greatness, and other publications. He received a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Rochester.

Dr. Peter Wood has served as president of the National Association of Scholars (NAS) since 2009. He was associate professor of anthropology at Boston University, where he also served as the president’s chief of staff; and he served as provost of The King’s College (NYC). Dr. Wood is the author of Wrath: America Enraged (2021) and 1620: A Critical Response to the 1619 Project (2020). He is also the author of several other books about American culture, including Diversity: The Invention of a Concept (2003); A Bee in the Mouth: Anger in America Now (2007); and Diversity Rules (2020). In 2019, he received the Jeane Kirkpatrick Prize for contributions to academic freedom. Dr. Wood is editor-in-chief of NAS’s quarterly, Academic Questions, and writes frequently for Spectator World, The New Criterion, The Claremont Review of Books, American Greatness, and other publications. He received a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Rochester.

Tweet of the Week

Deloitte's annual back-to-school survey found parents are more likely to purchase school supplies like pencils and notebooks this year as spending on tech devices is set to decrease. via @EdMarketBrief https://t.co/3EhoosMXMk

— Education Week (@educationweek) July 27, 2023