Why does a gender-gap persist in vaccination rates?

Men are more likely to die of COVID-19 than women: 13 men die of COVID-19 for every 10 women. Additionally, before the vaccine roll-out, 20% of women and 26% of men were worried about getting a severe case of COVID-19. Given these statistics, it can be assumed that men will be more proactive in getting their shots. So much so that experts worried about potential low-turnout among the historic anti-vaxxers, i.e., women.

However, this turned out to be untrue. As of June 29, 40.7% of men and 44.5% of women have been fully vaccinated in the United States. The trend is the same in Massachusetts, where Pioneer Institute’s database shows that 59.9% of women and 54% of men have been fully vaccinated.

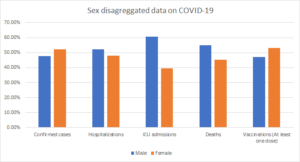

The chart above shows the percentage of confirmed cases, hospitalizations, deaths, ICU admissions, and vaccination amongst men and women in the USA. (Source: Globalhealth5050)

Why, despite initial vaccine hesitancy, are women leading the vaccination campaign? One explanation is that women constitute 55% of Americans aged 65 and above. Similarly, three-quarters of healthcare workers and 76% of public school teachers are females. These demographics received early vaccine priority, and therefore women got a head-start in vaccine access.

Additionally, women lost 5.4 million jobs, more than a million more than men, due to the pandemic. The loss of financial security, combined with the closure of child-care centers, schools, and assisted living facilities, increased caring-giving responsibilities for women. This may have made women more eager to do their part in ending the pandemic, increasing their willingness to take the vaccine so they could return to work.

Women also start seeking healthcare services from an early age due to the onset of menses and their disproportionate representation as unpaid caregivers. This increases the likelihood of women seeking healthcare services for themselves and others. Therefore, they may be more accustomed to the administrative processes of seeking healthcare than men.

However, these are not the only potential reasons why men are lagging. On average, men are reported to not seek dental care and go to the emergency room, even in a crisis. Traditional norms of masculinity that men should be physically strong, brave, and aggressive may make them less likely to seek healthcare.

But the experiences of men are not equal across different racial and ethnic groups. For example, in Los Angeles County, only 19% of Black and 17% of Latino men have received the first dose of vaccine, compared to 35% of Asian men and 32% of White men. Historical racial discrimination in healthcare services can, in part, explain the lower vaccination rates among Black and Latino men.

It is imperative to note that the vaccine hesitancy among men has decreased from 34% to 29% since February. However, it is still unknown if those figures hold for Latino and Black men. Additionally, a decreased hesitancy does not mean that men are getting the vaccine. After all, men reported a higher willingness relative to women to take vaccines before the rollout, but they eventually did not get the vaccine in the same numbers as women. Therefore, to ensure that men are getting vaccines, the messaging needs to target them as a demographic.

Maida Raza is a rising Senior at Earlham College. She is pursuing a Bachelors’s in Economics and Mathematics. Maida is working as a MassEconomix Intern at Pioneer Institute.