Where Are All the Workers?

Labor shortages are front and center once again this holiday season as Bay Staters make their way to retail stores for gift shopping. Help wanted signs line store windows, the occasional store is closed during hours when it would otherwise be open, and lines and waits seem longer as shorthanded staff try to accommodate the number of shoppers.

This has become a common story since the onset of the pandemic and it persists even now, long after virtually all COVID restrictions have ended. According to the most recent data from the Federal Reserve, over 10.3 million jobs remain unfilled in the U.S. That’s down from the record high of 11.9 million in March of this year but five times what the number was as recently as 2010. Currently there are 1.7 jobs for every unemployed worker in the country and 3.5 million fewer workers in the workforce than originally predicted by the Federal Reserve. In Massachusetts, there were 289,000 job openings as of September.

The lack of workers looking for jobs is not just a product of immigration restrictions, early retirements, and deaths that resulted from the pandemic, but a decades-long trend that only became more visible because of it. Decreasing birth rates, declining labor force participation from prime aged men (25-54), and retiring baby boomers have all been steering the labor market in this direction for a long time.

New England and, by extension, Massachusetts have been fortunate in the past to resist some of the labor participation rate declines the rest of the country has seen. One study by the Boston Federal Reserve found that even though New England has the oldest median age in the country, it also remains as one of the two highest census regions in terms of participation rate broadly across the workforce.

The high labor participation rate, or the percent of a population either looking for work or currently employed, has increased significantly since 2007 for the oldest workers (65+) and decreased at a slower rate for prime aged workers (25-54). Unfortunately, this insulation from labor force decline was not destined to last forever. The resulting labor shortages are being felt across several different industries and are likely to persist into the foreseeable future.

Hard Hit Industries

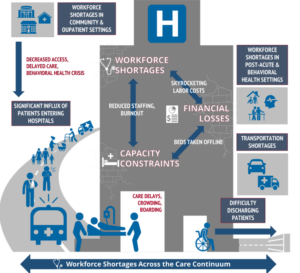

The Massachusetts healthcare system in particular is in crisis. One recent study by the Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association estimates that 19,000 acute care hospital positions remain unfilled. That statistic includes a vacancy rate of 56 percent for licensed practical nurse positions and an average rate of 17.1 percent across all positions. The study warns of increased wait times, worker burnout, “unprecedented backups in transferring patients to post-acute care services,” and rapidly rising labor costs that could put considerable financial stress on healthcare providers.

Source: “AN ACUTE CRISIS: How Workforce Shortages Are Affecting Access and Costs.” 2022. Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association.

Significant strain may be felt this winter with seasonal illnesses on the rise and a new surge of COVID cases. Depleted medical staff will have trouble handling the influx of new patients.

In response to the shortages, the Baker administration put forth a policy in October to stem some of the bleeding, offering to repay between $12,500 and $300,000 in government student loans for social workers, physicians, nurses, psychiatrists, and substance abuse recovery coaches, among others. The loans are a part of a $130 million program that aims to support and retain healthcare workers and is in addition to the $82.4 million the administration has already spent providing emergency staffing to nursing homes, rehab centers, and assisted living facilities around the state.

Other industries outside of retail, hospitality, and healthcare have also been hard hit. The professional and business services and educational services industries both have a higher-than-average percentage of job openings and manufacturing companies have had significant difficulties finding qualified candidates.

One study by Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute found that the manufacturing skills gap in the U.S. could result in as many as 2.1 million unfilled jobs by 2030. Skilled workers are in particularly high demand, not just in manufacturing, with 42 percent of businesses having openings for skilled labor. 89 percent of owners hiring or trying to hire reported few or no qualified applicants for open positions.

A mismatch between the skills and interests of workers and open jobs is a large factor in why 135,000 Bay Staters remain unemployed despite the record number of job openings. The Baker administration has recently tried to address the issue by investing $200 million in career pathways programs to retrain unemployed and underemployed workers.

No End in Sight

While the Federal Reserve interest rate increases will eventually cool the labor market, labor shortages will persist into the future. According to a recently updated study from MassINC, Massachusetts is likely to have 192,000 fewer working age college educated workers in the labor force by 2030. Retiring workers and declining admissions in the state’s higher education system will be primarily to blame.

Difficulty finding workers could potentially limit the ability of Massachusetts companies to grow and put a damper on the state’s economic prospects and dynamism.

Luckily, policy solutions are available to meet the need for additional labor, primarily in the form of immigration reform. If the country is unable to produce enough domestic workers to meet demand, the federal government should highly consider making reforms to our immigration system that will allow us to tap into the excess demand for American work and student visas. Specifically, increasing the number of H1B’s, removing the origin cap on EB-2’s, increasing work permit eligibility for asylum seekers, and loosening restrictions on OPT work authorizations under F1 student visas.

According to a recent Pioneer Institute paper, over 200,000 Indian applicants for EB-2 visas will die before they get approved to work in the U.S. and over 70 percent of H1B applicants will be denied before their cases are even adjudicated. These are not the signs of a functioning immigration system.

Unfortunately, immigration reforms are unlikely to be taken up anytime soon. In the meantime, Bay Staters will have to hope that the Baker administration’s policies will be enough to minimize the impact of the labor shortage and that the incoming Healey administration will follow suit.

About the Author

Aidan Enright is Pioneer’s Economic Research Associate, responsible for analyzing data and developing reports on the state’s business climate and economic opportunity. Prior to working at Pioneer, he worked as a tutor and mentor in a Providence city school and was an intern for a U.S. Senator and the RI Department of Administration. Aidan earned a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Economics with a concentration in U.S. national politics from the College of Wooster.