The role of old industrial districts in residential suburbs

The City of Waltham was once an aging mill town. Its flagship industrial corporation, the Waltham Watch Company, closed in 1957. The 1970s and 80s saw a decline in the industrial sector for the region as a whole.

Then, the tech companies came. Waltham has recently become a regional hub for biopharmaceuticals and therapeutic science alongside Cambridge. The western edge of the city is home to a momentous number of industrial firms that hug several bends in Interstate 95, towering over the Cambridge Reservoir.

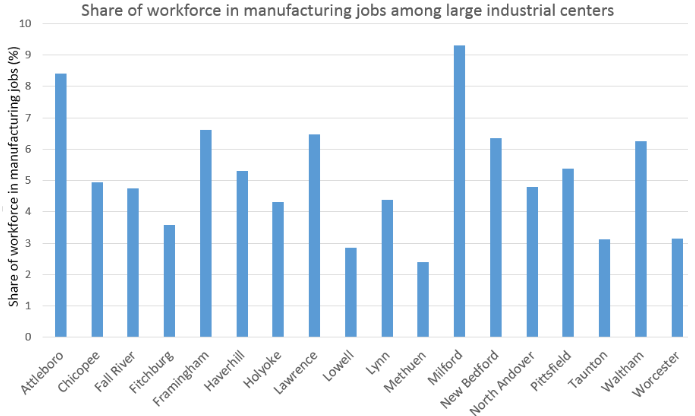

All the same, Waltham’s proximity to Boston gives its revitalization a different flavor than that of, say, Worcester or Lowell. As regional urban centers, Worcester and Lowell demand more diverse, service-based economies. Waltham retains over 6% of its workforce in manufacturing jobs to this day, while Lowell sits at under 3% (Figure 1). Comparing relatively small shares of the workforce might seem futile, but consider that Lowell is often credited with initiating the Industrial Revolution in the United States. Obviously, the gradual diversification of Lowell’s economy is a complicated development, but a notable catalyst was its large influx of Cambodian immigrants in the 1980s.

Manufacturing jobs in a wide variety of former industrial centers are compared in the figure below, with data from a state government agency overseer.

Figure 1:

While many older communities have a rapidly shifting economic identity in Massachusetts, most municipalities don’t have any large-scale manufacturing districts to work with. Communities like Newton – whose manufacturing districts are small and isolated – have long struggled with how to approach redeveloping the districts.

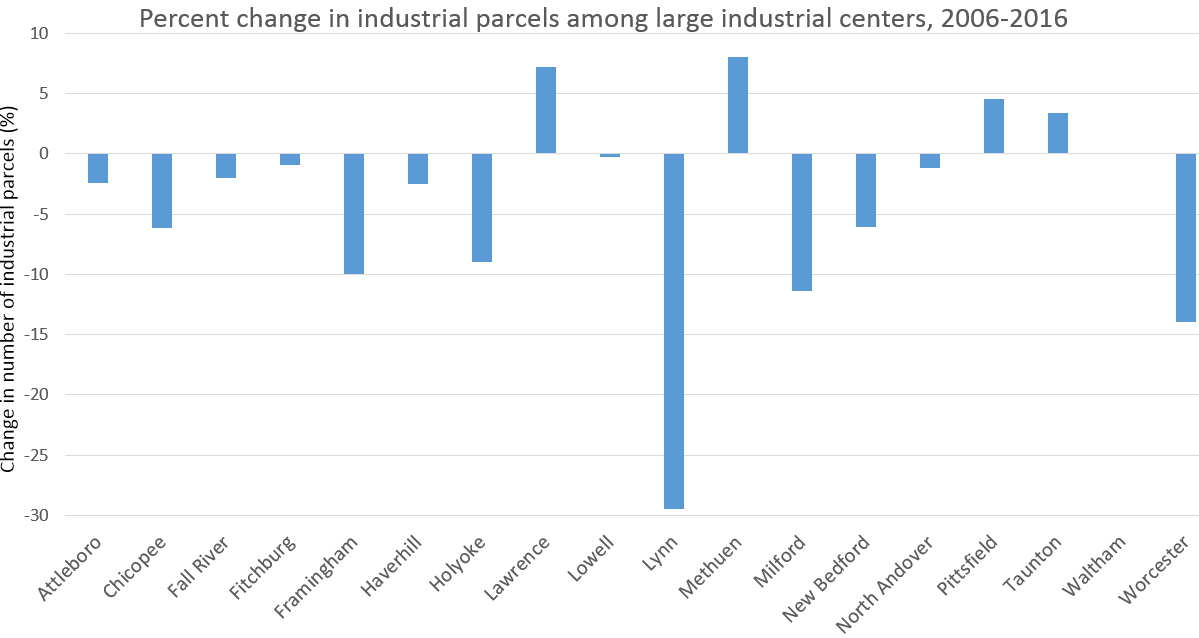

Several Boston-area communities have taken the lead on similar initiatives, including Lexington, Needham, and Somerville. Oftentimes, the goal of revitalizing old manufacturing districts to attract new industry serves to avoid overburdening residential taxpayers while facilitating local economic development. Still, there is a widespread trend of declining volumes of industrial parcels of land in former mill towns, according to Pioneer Institute’s MassAnalysis tool (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

The above graph suggests that there are market pressures for new home construction to replace industrial districts. Even fully revitalized Waltham is susceptible to this trend. Adding residential development to former areas of manufacturing can be a good way of keeping housing accessible and affordable in the midst of Boston’s recent housing boom. However, in communities that continue to rely on industry, such redevelopment need not serve as a missed opportunity for economic revitalization. Somerville, for example, has had it both ways with Assembly Square. Sitting on land that once hosted a Ford manufacturing plant, Assembly Square is responsible for 40% of the affordable housing units Somerville has added since 2010, yet is also home to dozens of retailers, a riverfront park, bike paths, and a MBTA stop.

Even as old industrial districts face market pressure to turn residential, some suburban communities have actively spurred on a resurgence in industrial jobs. Waltham did it some 30 years ago. Now towns like Needham and Lexington want in.

For more information on the economic health and tax information of local industry, visit MassAnalysis’ Metrics database.

Andrew Mikula is the Roger Perry Government Transparency intern at Pioneer Institute. He studies economics at Bates College.