Stonewalled at City Hall

Pioneer Institute interns often visit government offices to obtain or confirm information we may use in a blog. In this capacity, we made a trip to Boston’s City Hall to determine which retirement group Commissioner William Evans would fall into.

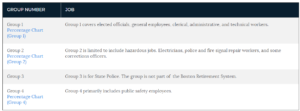

Public retirees in Massachusetts are broken into four groups that use different calculations to determine pension benefits. Group 1, which includes most employees, gets the least generous benefit, while members of Group 3 (the State Police) receive the richest.

While one would think the public could get an answer to the question online, it simply wasn’t that easy. The classification for group numbers on the City of Boston’s “Your Retirement Options” page is unclear and vague when it comes to police department personnel:

Group 2’s depiction doesn’t make it clear if it includes “police, and fire signal repair workers” or if “police and fire signal repair workers” describes a single occupation.

To confirm which retirement group Commissioner Evans belonged to, I (Pioneer summer intern) called the Boston Retirement System (BRS) identifying myself as a Pioneer intern. During the first call, I was told that police officers belonged to Group 2, but Commissioner Evans was in Group 4. They then sent me to the state retirement system’s database, which Evans is not a part of, before hanging up.

After calling back later to confirm the name of the woman she spoke to, I was told by BRS staff that it was unclear whom I spoke with and then told to contact another staff member, but the call went directly into voicemail. The next day, after getting no response, I called BRS again with the same result. The same cycle occurred six times over three days. After my email went unanswered, fellow intern Kaila Webb and I ventured to City Hall for answers.

We were lucky– unlike for many Boston residents, City Hall was just a six minute walk:

For those unfamiliar with City Hall, it’s an imposing building on Congress Street with an interior that reflects decades of artistic attempts to fix a harsh, concrete facade.

Boston City Hall. Source: Boston.gov

Our expectation was to walk in, get our question answered, and leave.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case.

Once in the Retirement Office, I was told I had to fill out two separate intake forms: one a normal sign-in sheet, and the other usually reserved for retirees. It was clear they knew it was I who left all the telephone messages. Still, after again asking which retirement group Commissioner Evans was in, I was told to include the last four digits of my social security number. The information I provided seemed to be the cost of admission. I was then told to have a seat.

After a few minutes, we were guided into a cubicle. It was there where we were told that anything they would tell us was off the record and unofficial. The staff member we spoke with never offered his name and told us not to take notes as he couldn’t represent the office.

As the mystery non-representative left, my email inbox received a thoroughly detailed response to my yes or no question from the BRS Executive Officer.

Perhaps all the secrecy at BRS was to protect retirees. But if they report that electrical engineers are part of Group 2 online, what difference does it make to confirm police commissioners work in Group 4?

It took 11 phone calls, four BRS employees, three days, two forms, and four digits of my social security number to get an answer to a simple question. If my experience is any guide, can you imagine how long it would take to get an answer to a tough one?

This article was co-written by Amy Tournas and Kaila Webb. Amy is a rising senior at Colby College studying Government and Global Studies, and a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern . Kaila Webb is the Wellesley College Freedom Project’s intern for the Pioneer Institute, currently double majoring in Environmental Studies and Chinese Language & Culture.