Investing in commercial development may ease fiscal woes without affecting crime

Bedford, Massachusetts is a suburban town of about 14,000 in the heart of Middlesex County. Its Wikipedia page boasts a charming picture of a historic train depot engulfed in fiery fall foliage. Driving through Bedford at night, you would hardly notice the slew of tech companies and manufacturing operations tucked into a corner of the town next to Route 3, the numerous hotels and motels that dot Route 4, or the community college that cozies up to the Billerica town line. During the day, however, Bedford’s population more than doubles because of people who are employed at all these establishments. The town’s employment/residence ratio is 3.44, almost twice that of Boston.

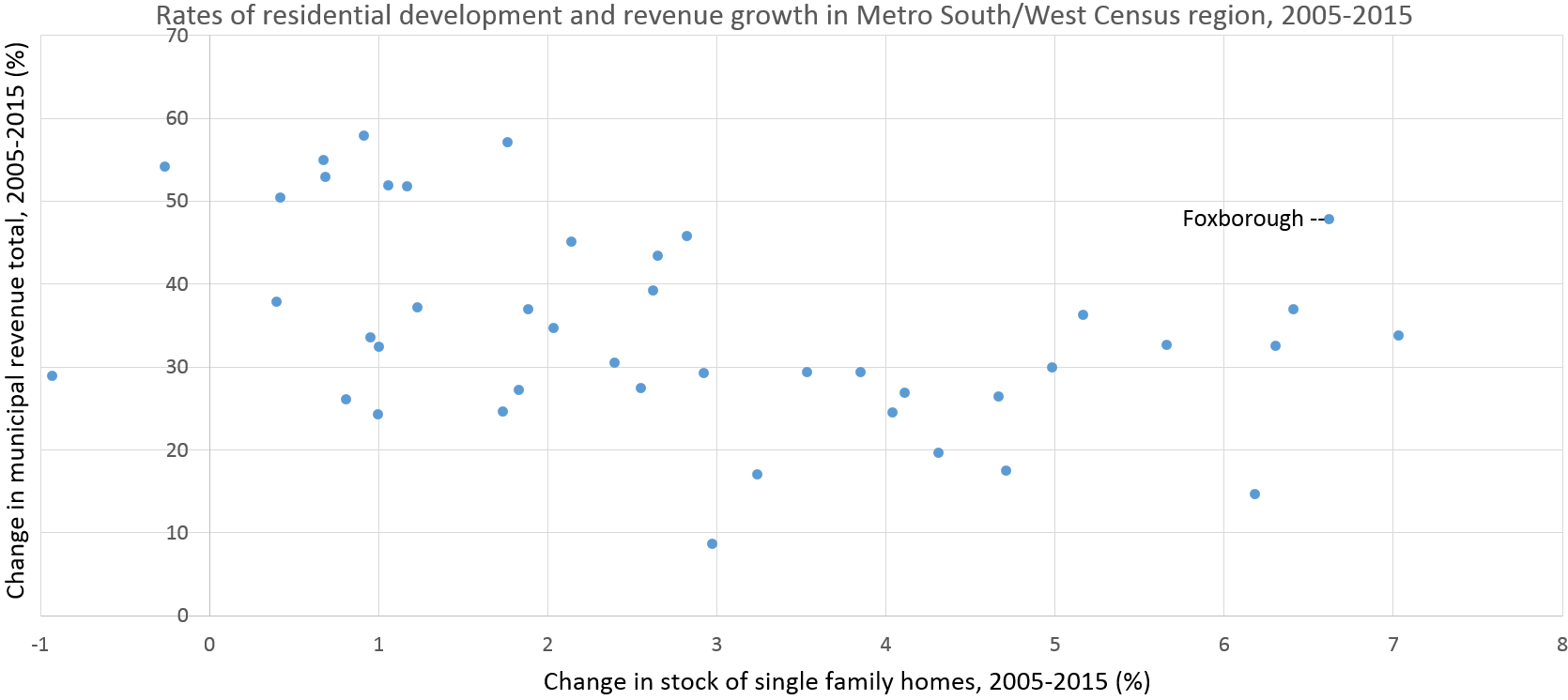

“Daytime population,” essentially a measure of population that accounts for commuting patterns, has been referred to as the most important population statistic. Not only does it speak volumes about the economy and transportation, but it’s also a significant consideration in disaster relief planning. In addition, attracting employers in an otherwise residential community can help make municipal finances more sustainable. Research has repeatedly shown that sprawling residential developments cost municipalities more in services and school expenditure than they make up for in property taxes and household spending practices. In Figure 1, I compare revenue growth with changes in single-family parcel development over time among towns in the Metro South/West census region, which includes Bedford. The municipal revenue data comes from Pioneer Institute’s MassAnalysis Metrics tool.

Figure 1:

There’s a modest negative correlation, meaning revenue growth is depressed by excessive single-family housing development. The reason the correlation isn’t stronger is likely because residential and commercial development can be simultaneous. Crowding out effects are possible, but confounding variables are plentiful depending on the kind of commercial development that’s prevalent in a town. Foxborough, for example, is a notable outlier in Figure 1 in that its residential development and revenue growth have both been strong and positive over the period of study. This is likely related to the fact that Gillette Stadium paid the town of Foxborough record dues in shares of ticket revenue in 2008 and again in 2014. It’s not every day that a celebrity billionaire builds a giant revenue magnet in a town of 17,000 while largely covering constructions costs himself. Most suburban communities face real trade-offs between succumbing to residential development pressure and facilitating revenue growth.

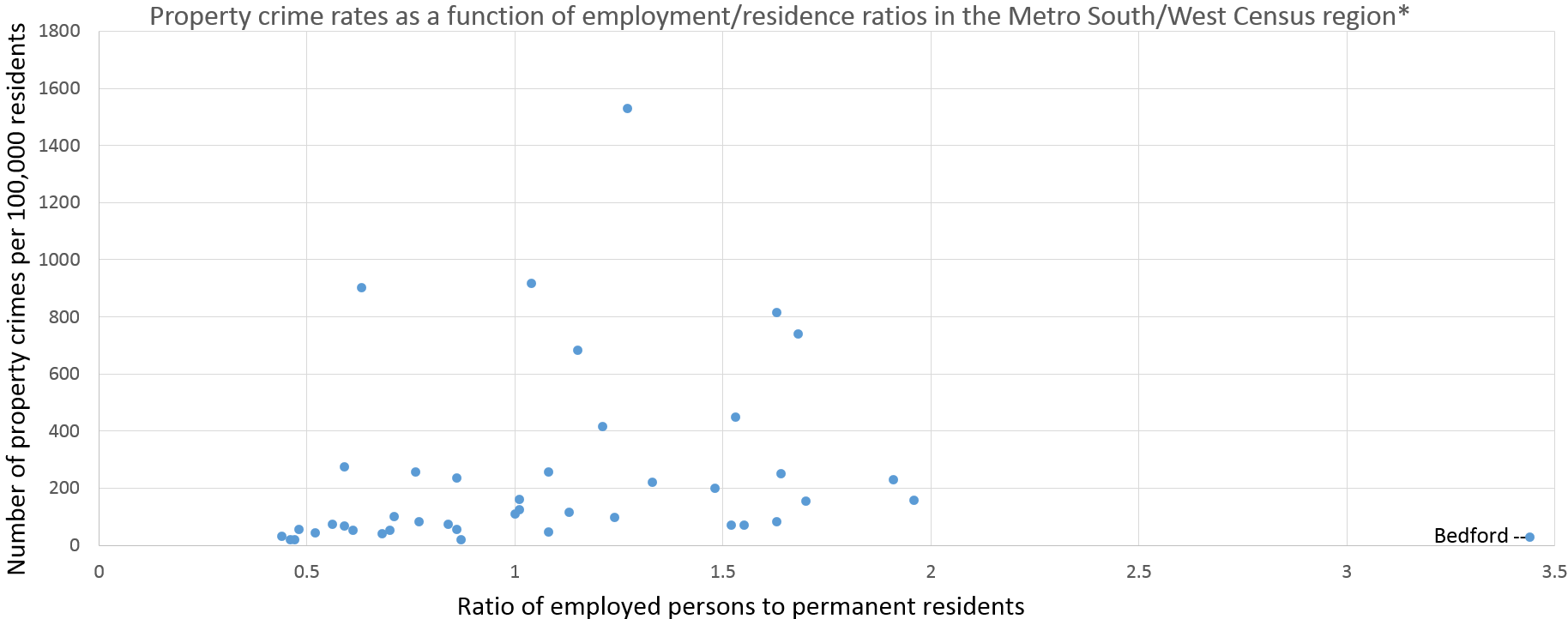

Despite the budgetary boons of commercial development, residents of some small towns with large employment centers worry that a large influx of people into their communities every day will lead to increases in crime, particularly property crimes like burglary and shoplifting. In Figure 2, I compare the property crime rates of towns in the Metro South/West census region with employment/residence ratios.

Figure 2:

*The employment/residence ratio data is from the 2000 Census. Property crime data is from the closest year to 2000 that was available on MassAnalysis for a given town.

The only notable trend in this crime data is that there isn’t one. The sporadic nature of this relationship suggests that employment hubs don’t automatically have more crime than commuter towns.

Still, the debate over the relationship between commercial development and crime requires a bit more nuance depending on the kind of commercial development. Putting a Whole Foods into your community probably won’t increase crime significantly. Putting in a row of nightclubs, bars, and pawn shops probably will.

Overall, small towns shouldn’t shy away from commercial development. Besides the fiscal impacts, establishing commercial centers in suburban areas could help reduce vehicle miles traveled, enhance a sense of neighborhood identity, facilitate opportunities for small business, and eliminate food deserts.

The same logic applies to poor urban areas whose struggling local economies are overshadowed by the success of downtown business districts on citywide reports. More commercial development should go where people already live, even if, during the day, they’re somewhere else.

For more information on municipal finance, visit Pioneer Institute’s MassAnalysis database.

Andrew Mikula is a rising senior at Bates College majoring in economics. Since joining Pioneer Institute as the Roger Perry Government Transparency intern, he has focused on using Pioneer’s MassAnalysis database to analyze social and economic issues. He aspires to be an urban planner upon graduation.