In the past few years, the tobacco industry has thrived in Massachusetts. Here’s why.

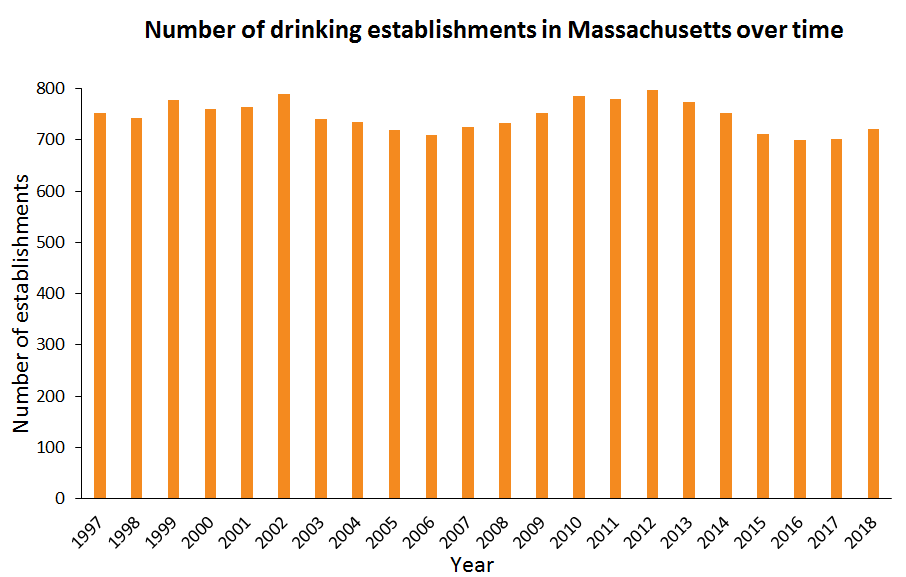

Despite recent good news about declines in alcohol, traditional cigarette, and hard drug use among young people, it seems that retailers of these heavily regulated (or just plain illegal) substances aren’t going away any time soon. The number of Massachusetts bars and nightclubs – or, in the words of the Census Bureau, “places primarily engaged in preparing and serving alcoholic beverages for immediate consumption” – has wavered between about 700 and 800 since the late 1990s in a pattern that, amusingly (and probably coincidentally), seems countercyclical (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Source: Your-economy Time Series

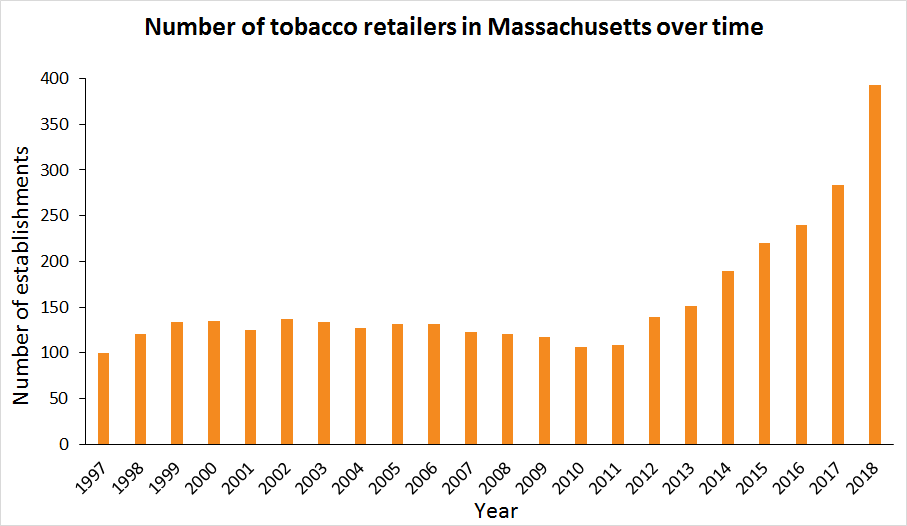

However, more concerning than the trend in drinking establishments is the trend in tobacco stores, defined as “establishments primarily engaged in retailing cigarettes, cigars, tobacco, pipes, and other smokers’ supplies.” In the last decade or so, Massachusetts has seen an explosion in these retailers, from 106 in 2010 to 393 in 2018 (see Figure 2). While a strong economy is likely a factor, data obtained by the Pioneer Institute for our new economic analysis tool reveals another big reason: in 2018, 24% of Massachusetts tobacco stores had the word “vape” or “vapor” in their name. As late as 2012, it was fewer than 1%.

Figure 2:

Source: Your-economy Time Series

Consumption of electronic cigarettes, also known as vaping, has overwhelmed regulators as a string of new products that often look like writing implements or flash drives have threatened to get a new generation hooked on nicotine. The pervasiveness of vape-oriented retail in Massachusetts goes beyond the 393 stores in Figure 2, as this data is self-reported and likely excludes convenience stores, gas stations, and other establishments that are not often characterized as “tobacco stores.”

In terms of business, the e-cigarette trend is also striking for its geographic diversity. Long a staple of gateway cities and urban enclaves, smoke shops are now spreading to rural towns and far-flung “country suburbs.” The sprawling I-495 burgs of Middleborough and Tewksbury each have multiple tobacco retailers. Moreover, the share of tobacco stores in MAPC-designated “Metro Core Communities” (places like Everett, Chelsea, Malden, and Somerville) declined from 22% to 19% between 2010 and 2018. While this is not a dramatic decline, it reflects the spread of smoke and vape shops to all corners of the state. Since 2017, every county in Massachusetts has had at least one tobacco store, and since 2014 every city with a population above 50,000 has had one too.

Moreover, vape shops appear to be most common where there is a large population of young people. This is evidenced by the negative correlation between median age on the county level and the number of tobacco stores per capita. With the exception of Hampshire County, whose age demographics are skewed by the presence of UMass Amherst, counties in Massachusetts with below-average concentrations of tobacco stores all have median ages above the national average of 38. That is, counties with older populations on average tend to have fewer tobacco stores.

The upshot is that electronic cigarettes have breathed new life into the tobacco industry, potentially elevating the prevalence of nicotine addiction in the state for decades to come. At the current decade’s rate, the number of tobacco stores will surpass the number of drinking establishments in Massachusetts by 2026.

Andrew Mikula is the Lovett & Ruth Peters Economic Opportunity Fellow at the Pioneer Institute. Research areas of particular interest to Mr. Mikula include urban issues, affordability, and regulatory structures. Mr. Mikula was previously a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern at the Institute and studied economics at Bates College.

Receive Our Updates!