Unemployment: A Massachusetts vs. New England Comparison

In 2021, New England had the third-highest regional unemployment rate in the United States at 5.5 percent, while the national average unemployment rate was 4.83 percent.

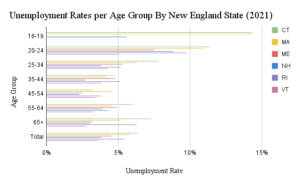

Compared to the other New England states, Massachusetts had the second-highest total unemployment rate that same year. Most notably, Massachusetts tied for the highest unemployment rate for those aged 16-19 and had the most unemployed 45-54 year olds at 14 percent and 5 percent, respectively. While Massachusetts does not have a consistently wide variance from the other states in the region, it is important to note that the Bay State regularly exceeds the rates of most New England states.

Fig. 1. Source for Analysis: Labor Analytics. Note: ME, RI, and VT values for the unemployment rate of the 16-19 age group in 2021 were not available; so, they are not shown in that portion of the graph.

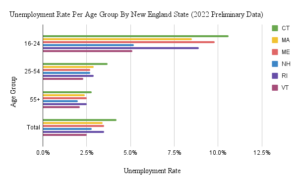

Fig. 2. Source for Analysis: Labor Analytics

In 2022, Massachusetts fell to fourth highest among the New England states with an unemployment rate of 3.4 percent, which was in line with the national average of 3.6 percent. However, as of April 2023, Massachusetts once again had the second-highest unemployment rate in New England, 3.3 percent. Meanwhile, New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont were all among the states with the 10 lowest unemployment rates in the United States with rates of 2.1 percent, 2.4 percent, and 2.4 percent, respectively. Evidently, as surrounding states seem to have continued to tamp down unemployment, Massachusetts has remained stagnant.

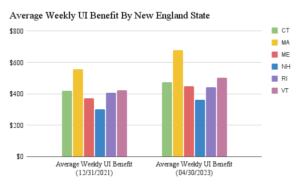

Massachusetts also has the richest unemployment benefits in the region. For instance, the Commonwealth’s average weekly payout in December 2021 was $556, $143 above the regional average of $413. The difference between Massachusetts benefits and those in the region have continued to grow, as the most recent data from April 2023 shows that the average weekly payout in the state was $677, $192 above the New England average.

In addition, Massachusetts is one of the only states that has a maximum benefit duration of 30 weeks, as many others only allow up to 26 weeks. Thus, Massachusetts has a consistently high unemployment rate in comparison to other New England states, while it also pays a larger average weekly benefit and allows for a longer maximum period for which beneficiaries can collect unemployment insurance.

So, it’s important to ask: Is there a correlation between the amount of UI a state allows to be dispensed and the state’s unemployment rate? According to Robert Moffitt of Johns Hopkins University, “A side-effect of unemployment benefit programs is that they may encourage people receiving benefits to search less intensively for a new job than they would have otherwise…” (Source: IZA World of Labor) which would in turn cause the unemployment rate to be higher.

Regarding the moral hazard problem that unemployment benefits can create, Moffitt explains, “In the absence of unemployment benefits, the gain is simply the wages on the new job. With unemployment benefits that gain is reduced to the difference between the unemployment benefits and the wages paid by a new job because the payments cease when someone becomes employed.” (IZA World of Labor).

Then, he identifies an issue caused by unemployment benefits resolving the liquidity constraint problem as he says, “…unemployed workers with few assets would have to reduce their consumption even though it is likely that they will eventually find a job and earn income… An unemployment benefit program relieves this pressure and allows unemployed workers to maintain consumption without having to accept an inappropriate job.” (IZA World of Labor).

Ultimately, this means Massachusetts legislators should remain vigilant of the ways in which unemployment insurance can affect the duration of unemployment and the incentive to find new work so as to mitigate the possibility of facilitating an even higher unemployment rate.

About the Author: Sarah Delano is a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern at the Pioneer Institute for the summer of 2023. She is a senior studying Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.