Massachusetts Remains One of the Least Financially Transparent States

In 48 states, elected officials are required to submit annual public financial disclosures. Among these states, Pioneer Institute ranks Massachusetts lowest in terms of the transparency of those financial disclosures.

Statements of Financial Interests (SFI’s) are designed to provide government transparency by giving the public some visibility into the financial information of public officials. They allow voters to see if officials’ actions could be viewed as being in their personal interest rather than the public’s interest. The SFIs are available to the public for inspection upon request.

Seven years ago, Pioneer identified three problems with the commonwealth’s financial disclosure system in its study Weak and Out of Reach, and recommended ways to improve the disclosures.

In the years since, we ask, what, if any, improvements have been made to improve the disclosures policymakers file?

- Real Estate values and income

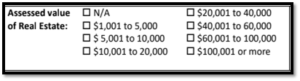

The last time Pioneer reported on the SFI forms, a major shortcoming was the brackets used to describe the value of real estate holdings.

As seen in the figure above, real estate value brackets are the same as they were 44 years ago when the State Ethics commission was created, despite soaring prices. Today it would be nearly impossible to find any Massachusetts real estate valued less than $100,000, yet “$100,001 or more” is the top bracket on the form. Income brackets haven’t changed either, with the maximum bracket remaining at $100,001 or more.

These real estate and income values lack relevance and aren’t keeping up with the times.

2. Debt

Debt disclosures remain limited, just as they were seven years ago. Despite the fact that outstanding debt worth more than $1,000 must be reported, some debt can go unreported if it is related to retail installment transactions, educational loans, medical and dental expenses, debts incurred in the “ordinary course of business,” and alimony and support payments..

Additionally, after seven years there still exists no requirement for public officials to disclose who their private clients are in the financial disclosure law.

3. Accessibility

SFI accessibility remains concerning, although it has been improved in recent years. According to the Mass.gov website, “SFIs are public records and may be requested by the public. The financial disclosure law, G.L. c. 268B, provides that an SFI shall be available for public inspection and copying upon written request of any individual.”

Though SFI’s can be searched and filtered through online, a requestor must upload his or her license or other identification to gain access to them. In addition, “the law further requires the Commission to notify the filer of the name and affiliation, such as a newspaper, magazine, or campaign, if any, of the individual who has viewed their SFI.” This stipulation essentially eliminates anonymity, and potentially puts requestors at risk. As Kevin Lawson of Pioneer had put it seven years ago, “How many people would request them knowing that the filer, typically in a position of some power, could contact them and question their motives?”

4. What needs to change?

First and foremost, the public should be able to access information on their public officials without fear of reprisal or intimidation. To this end, the identity of someone who requests an SFI should not be revealed to the public official whose form he or she is requesting. Anonymity must be guaranteed to all those who request SFI’s. Additionally, the State Ethics Commission should address and mitigate the shortcomings in debt and clientele disclosures.

About the Author:

Etelson Alcius is a roger perry transparency intern with the Pioneer Institute. He is a recent graduate of Cathedral High School and incoming freshmen at the College of the Holy Cross, where he intends to double major in economics and computer science on a prelaw track. Feel free to reach out via email, linkedin, or write a letter to Pioneer’s Office in Boston.