Study: Inefficient Public Pension Investment Costs Taxpayers About $100 Million A Year

Local systems forfeited some $2.9 billion over 30 years by not investing with PRIM,

probably billions more if fees and compounding are included

Read coverage of this report in the Boston Herald, The Bond Buyer, and Associated Press.

BOSTON – The commonwealth should set a five-year deadline for 102 public pension systems to transfer their assets to the Pension Reserves Investment Management (PRIM) Board, the management authority for the Massachusetts State Employee Retirement System (MSERS) and the Massachusetts Teachers Retirement System (MTRS), according to a new Policy Brief published by Pioneer Institute.

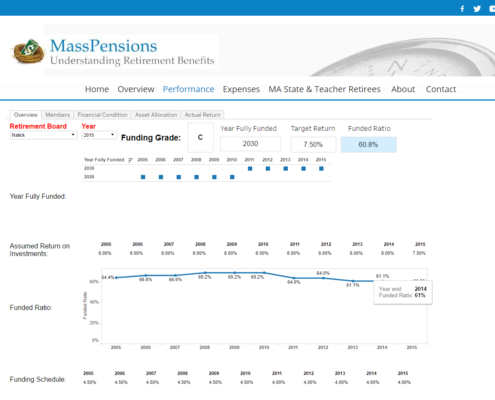

From 1986 to 2015, the difference in gross returns between non-state public pensions (i.e., excluding the MTRS and MSERS) and PRIM implies a taxpayer loss of more than $2.9 billion. Dr. Iliya Atanasov, author of “Massachusetts Public-Pension Investment Reform,” finds that the systems forfeited nearly $1.6 billion from 2000 to 2015 alone by not investing with PRIM, or $97 million a year.

The real performance gap is almost certainly much larger, since the estimates were based on annual beginning assets and gross returns, which don’t take into account PRIM’s lower investment expenses and the effects of compounding. PRIM offers better asset allocation and cash management, lower investment fees and other costs, and more attractive investment options due to its size and market power.

“Local taxpayers are ultimately on the hook when pensions are underfunded,” said Pioneer Executive Director Jim Stergios. “This is going to sound really elementary, but it’s critical we don’t forfeit billions of dollars in investment returns.”

The MSERS and the MTRS account for about two thirds of all Massachusetts public pension assets and their assets are statutorily managed by PRIM. A 2007 state law required that pension systems that are less than 65 percent funded and whose average returns trailed PRIM’s by at least 2 percentage points over the prior decade transfer their assets to PRIM.

Dr. Atanasov’s analysis says the law was a step in the right direction, but did not go far. For example, a system that has annualized returns of 8 percent over a decade would reap 20 percent more than one whose returns were two percentage points lower.

Even before passage of the 2007 legislation, more local systems had begun to move their assets to PRIM. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of local systems fully invested in PRIM nearly doubled from 19 to 37, and the number that were partially invested more than tripled from 17 to 53.

From 1986 to 1996, PRIM achieved annualized gross returns of 11.45 percent, while systems that were partially invested achieved 10.62 percent and returns for non-PRIM funds were 10.32 percent.

From 2000 to 2015, PRIM’s annualized gross returns were 5.8 percent, partially invested systems generated 5.4 percent and non-PRIM systems returned 5.3 percent. The gulf for both time spans adds up to an unrealized $2.09 billion, not including forgone compounding and PRIM’s lower fees.

Short of the five-year deadline for transferring local pension assets to PRIM, state policy makers should at least require all local systems that are less than 90 percent funded to transfer their assets. Municipalities should also have the power to compel local retirement boards to move their assets to PRIM. Retirement boards can be given a broad range of investment options under PRIM’s segmentation program.

About the Author

Iliya Atanasov is Pioneer’s former Senior Fellow on Finance, who spearheaded research on pension management, budget analysis, infrastructure and municipal performance. Iliya received his PhD in Political Science from Rice University, where he was a Presidential Fellow. He also holds BAs in Business Administration, Economics and Political Science/International Relations from the American University in Bulgaria.

About Pioneer

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.

Get Connected!

Related posts: