Explosion in ESL enrollment creates new opportunities, challenges

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that, between 2010 and 2019, the population of Massachusetts grew by 344,718 people. It also estimates that, without immigration, the population would have declined by 17,052.

Immigrants have played an increasingly important role in the Commonwealth’s economy and culture over the past few decades, as the state has relied on international arrivals to offset out-migration among native born residents. Since 2000, there have been only two years in which the number of Americans moving to the Bay State was greater than the number of Massachusetts residents moving to other states. Every year from 2008 to 2018, immigrants ensured that the Commonwealth’s population kept growing by offsetting the losses that came from Bay Staters moving to places like North Carolina, Florida, and Arizona.

Still, this amounts to an influx of immigrants that Massachusetts hasn’t seen in decades. In 2000, Massachusetts welcomed under 20,000 net international migrants, compared to over 38,000 in 2018. With this large increase in immigration comes several challenges, from financial responsibilities to racial tensions.

However, one of the most readily apparent concerns to immigrants and native-born citizens alike is the resulting English language barrier, which can render it difficult for immigrants to integrate into their new communities, get a job, or access government services. It also leaves their children much less likely to graduate high school or receive satisfactory scores on standardized tests.

Between 2009 and 2018, the number of Massachusetts schoolchildren who speak a language other than English at home grew by 19.6 percent, to some 244,000. There are now over 50 school districts in the state in which English Language Learners (ELLs) make up at least 10 percent of the student body, and 18 districts where ELLs make up at least 20 percent. In an attempt to respond to these changing demographics, many school administrators have scrambled to hire bilingual teachers, retrain existing teachers, and expand English as a Second Language (ESL) programs at their schools. Unfortunately, the state’s formula-based funding approach for ELL students is increasingly insufficient, and ELL students are overwhelmingly concentrated in communities that heavily rely on state funding to finance public education.

Since 2008, ESL program enrollment has grown faster in rural and suburban towns than in larger cities in Massachusetts. Still, suburban communities often have a small percentage of their student bodies in ESL programs overall, and they are more likely to have the resources to increase spending on the programs as needed. Below, Figure 1 catalogues the persistent disparities in the share of ELL students between urban and rural municipalities.

Figure 1: The share of students who are English Language Learners by community type over time

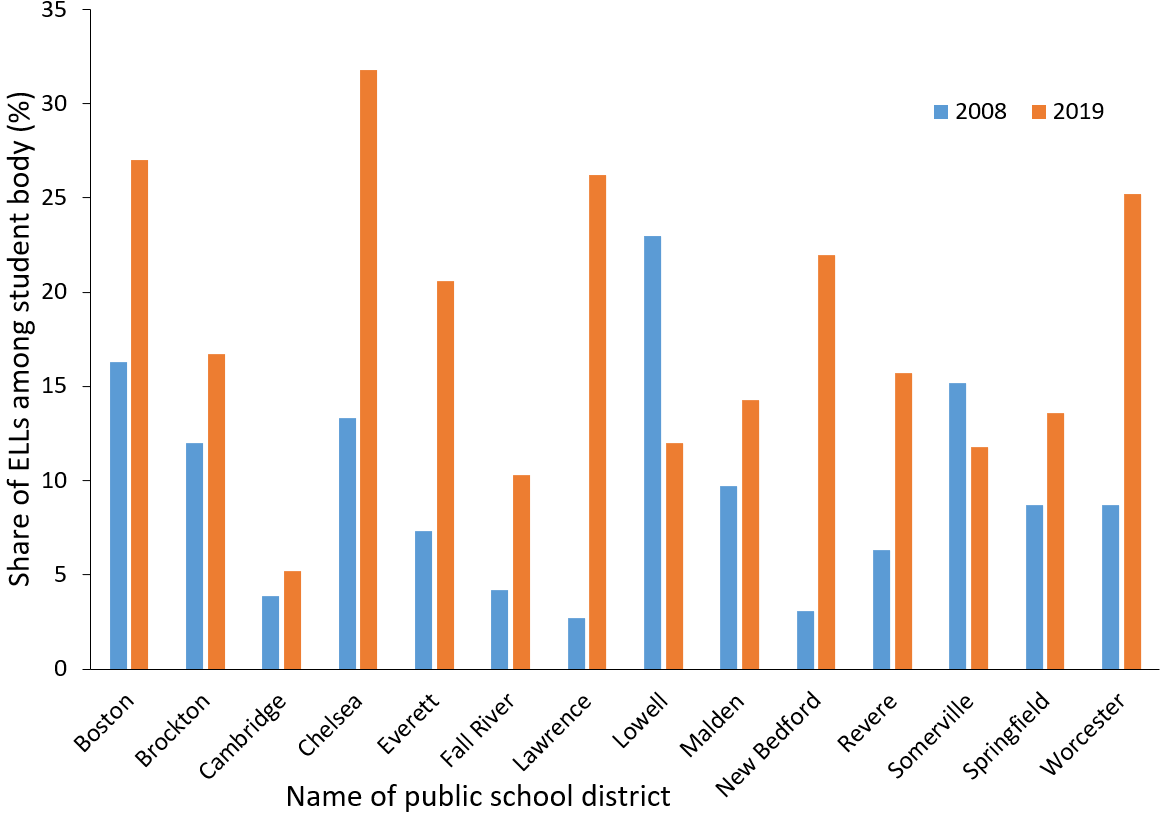

While the growth of ELL students overall in the past 11 years is remarkable, certain communities have received a disproportionate number of them, especially gateway cities that are relatively close to Boston. In some of the most dramatic examples, Lawrence Public Schools and New Bedford Public Schools both saw their concentrations of ELL students rise from roughly 3 percent in 2008 to well over 20 percent in 2019. On the district level, growth in the share of ELL students is presented in Figure 2 for both Metro Core Communities and Major Regional Urban Centers.

Figure 2: The share of ELL students in major urban public school districts over time

Notably, Lowell and Somerville buck the trend, with substantial declines in the share of ELLs in their public school districts. Cambridge and Malden also have slower growth in ELL student concentration than other urban public school districts, but this may be due in part to recent gentrification in these communities. Meanwhile, the only cities with the five largest shares of ELL students in either year that aren’t in the Metro Core Communities or Major Regional Urban Centers categories are Southbridge (27 percent ELL students in 2019) and Lynn (17 percent in 2019). Both are classified as “Sub-regional Urban Centers” by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council. Otherwise, the urban public school districts in Figure 2 exemplify the explosion in ELL students that Massachusetts has seen in recent years.

Still, growth in ESL programs in municipally operated schools alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Charter schools have taken on an enormous role in the expansion of ESL programs throughout the state. In 2019, 25 charter schools had at least 10 percent representation of ELL students, more than the 17 charter schools that had any at all in 2008. Moreover, 11 of the top 20 school districts by the share of ELL students enrolled are charter schools, up from just one of the top 20 in 2008. That school district, the Phoenix Charter Academy network, is currently the only one in the state with more ELL students than non-ELL students.

Massachusetts charter schools are often located in urban areas, which puts them in a good position to grow their ESL programs, as immigrants still generally concentrate in gateway cities. Charter school enrollment is also still growing in general. Moreover, charter schools may be able to respond more effectively to the growing and evolving needs of ELL students because their finances are largely independent of municipal revenue streams.

Regardless of the preparedness of a district to accommodate more ELL students, demographic data indicate that their representation in public school systems will only grow in the coming decades. After all, most ELL students are second-generation immigrants whose parents do not speak proficient English, and the children of the 362,000 immigrants who have come to Massachusetts since 2010 are still being born.

The Commonwealth must do more to give these students an education that will allow them to thrive for decades to come. This includes reducing ESL teacher shortages, soliciting block grants that increase the ability of school districts to respond to student needs as they arise, and giving the students and their parents a voice in evaluating and improving the ESL programs. The wellbeing of a new generation of Massachusetts residents depends on these reforms.

Andrew Mikula is the Lovett & Ruth Peters Economic Opportunity Fellow at the Pioneer Institute. Research areas of particular interest to Mr. Mikula include urban issues, affordability, and regulatory structures. Mr. Mikula was previously a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern at the Institute and studied economics at Bates College.