Massachusetts Confounding Relationship with Lottery Advertising

In 2015, Massachusetts State Treasurer Deborah Goldberg called for a $2 million boost in the State Lottery’s advertising budget. According to Treasurer Goldberg, the additional money is needed to counter the competitive threat posed by the state’s growing casino industry.

The Lottery’s advertising budget has had a volatile history. In the 90s, it was central to an ideological debate that split Beacon Hill for years before the Senate finally slashed the budget for good. In the early 2000s, the budget was steadily restored – and now, thanks to Treasurer Goldberg’s latest push, it has reached its highest point in the last decade.

But two fundamental questions – questions we’ve been asking since the 90s – remain. From the one-dimensional viewpoint of profit-making: does advertising actually sell more tickets? From a broader, societal perspective: is Lottery advertising ethical?

There aren’t solid answers to these questions. But they’re both worth considering – especially in the context of the Lottery’s latest advertising increase.

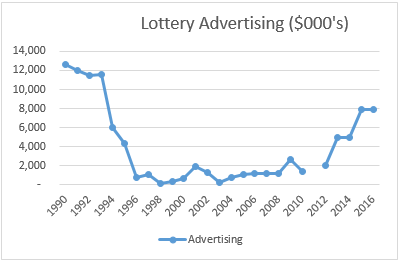

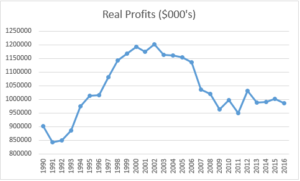

Does an increased advertising budget increase profits? Surprisingly, there’s no immediate correlation between profits and advertising expenditures. In fact, the Lottery’s advertising budget is negatively correlated with profits in the long-term. I’ve graphed the two together below. The Lottery budget decreased greatly – from $12 million to around $400,000 – in the early to mid-1990s. And yet, profits during this time continued to increase substantially. In the early 2000s, as advertising increased, real profits stagnated before tumbling into the new decade.

This would seem to prove that the Lottery’s advertising expenditures have no positive impact on its profits. Treasurer Goldberg, however, claims that the Lottery has studied and proven that advertising does have a positive effect on profits – although this does not reveal itself in long-term data. In the past, Lottery officials have argued that advertising has a long-term effect on sales and that profits don’t respond immediately to advertising decreases but may take years, even decades, before having an impact. The theory isn’t implausible – in fact, one could argue that the data may support it. The drop in profits resulting from the mid-90s cuts may have been realized in the 2003 – 2010 period of stagnation.

But this sort of speculation seems convenient. In the end, there is no clear evidence that a large advertising budget has helped the Lottery’s sales, and unless such evidence is revealed, the Massachusetts taxpayer should be skeptical. The Treasurer’s concern regarding the casino industry is legitimate, but increased advertising is not necessarily the answer.

So, onto the second, and perhaps more interesting question: is Lottery advertising ethically justified? Many argue that a state-run lottery amounts to a tax – a regressive tax, specifically. People with lower incomes are more likely to buy lottery tickets, and in Massachusetts, this means that local government aid, much of which is generated through the State Lottery, comes from the pockets of the state’s poorest citizens. This is a reality that all state lotteries must accept. But luring people with lower incomes to gamble away their money with a targeted advertising scheme seems morally dubious, and it raises the question whether government should be involved at all.

This was central to the 1990’s debate over Lottery advertising. The Senate, led by Ways and Means Committee Chair Tom Birmingham, now at Pioneer Institute, lobbied for a stark cut in the budget. The initiative was fiercely opposed by the State Treasurer at the time, Joe Malone, but it was enacted over the course of three years in a series of large cuts.

Birmingham explained his motivation for wanting to enact the tax.

“The Lottery is as regressive a way possible to raise revenue. Participation is inversely related to wealth, which is true across the entire state.”

He went on to note that he would have liked to make the Lottery more progressive, but this would have been extremely contentious. So, instead, Birmingham pushed for a cut in Lottery advertising on the moral grounds that it was wrong for the State to convince people to gamble.

Birmingham described the naturally divisive dynamic of Lottery budget allocation that plagued the debate in the 90s.

“The Treasurer was institutionally against (the cuts),” said Birmingham.

He also mentioned that historically the Lottery was run like an “empire,” and that Treasurers were vehemently against any policy that could hurt profits. According to Birmingham, right after he left the Senate, the Lottery budget began to increase.

“I thought I had convinced people that Lottery advertising needed to be cut. But I was really just in a position where I would command and they would obey.”

The Lottery debate in the 90s encapsulates the today’s conundrum. The State Treasurer will always be obliged to support Lottery advertising, and cost-cutting mechanisms will be looked upon with skepticism.

The Lottery is a cash cow, and it is understandable the State wants to protect the industry. But advertising hasn’t been shown to necessarily increase profits, and it may not be entirely ethical. The rise of the casino industry adds a third variable into this scenario. But even so, without empirical data supporting the need for a large Lottery budget, the Massachusetts taxpayer should be leery about any increase.