Will All-Electronic Tolling Save Money?

This blog explores the State’s switch to an all-electronic tolling system from a financial perspective. For a more general review of the changes to come please see our full report.

Before gantries for all electronic tolling began to appear on the Turnpike, state officials underscored numerous projected benefits associated with the change, including a reduction in accidents and emissions, lessened congestion, and, notably, a sizable reduction in operating costs. Now that the new system is set to become fully operational, some of these claims are coming under closer scrutiny.

In 2013, before the Tobin Bridge pilot program began, the state claimed that the new system would save $50 million annually in operating costs. It is worth noting that such claims were problematic in that operating costs do not tell the whole financial story of the change.

Last December, Transportation Secretary Stephanie Pollack pulled back on the estimate made by the previous administration, saying that the savings would be closer to $30-40 million annually. Yet even that claim of savings was overly optimistic, especially given that the month before, Highway Administrator Thomas Tinlin made a presentation which argued that much more modest savings would result from all-electronic tolling.

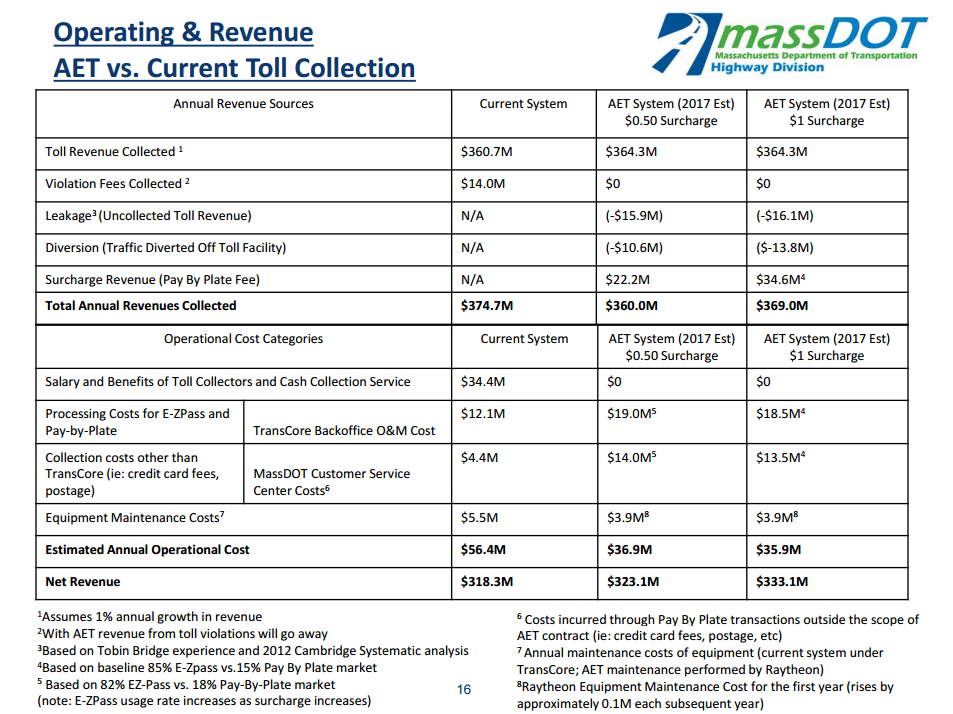

One of the slides from this presentation, pictured below, shows that although the new system was projected to save approximately $20 million in operating costs, much of these savings would be offset by approximately $14 million in reduced revenue, resulting in a bottom-line impact of only $4.8 million dollars.

This estimate hinges on the number of drivers without transponders who pay their mail-in bills through the Pay-By-Plate system (PBP).

(Image source: All-Electronic Tolling Update)

The spreadsheet in the presentation shows that MassDOT expects to lose about $15.9 million in ‘leakage’ (unpaid PBP bills), representing 4.4 percent of total tolling revenue. Even a slight change in this projection, for example up to 5.7 percent of revenue, would eliminate the remaining $4.8 million in cost savings.

Additionally, this spreadsheet covers only annually recurring costs and revenues, such as operations or maintenance. One-time costs associated with the switch to all-electronic tolling, hundreds of millions to tear down toll booths, put up gantries, lay off toll-workers, build a new customer service center, and more, are not included.

While there could be significant variations (higher or lower) in actual results, the financial argument behind the switch to all-electronic tolling evaporated. The $50 million savings estimate by the Patrick Administration was never realistic, and even large savings in operations are mostly offset by ‘leakage’ losses.

So, then, what of the other supposed benefits?

National and state studies both find that merge zones before and after toll plazas have a higher concentration of accidents than other stretches of highway. This, combined with the removal of toll workers, will certainly make the highway a safer place for all drivers.

Lessened congestion, emissions, and trip times are all intimately tied together. Removal of toll plazas may help alleviate patches of traffic during off-hours and contribute towards quicker trip times, but during peak hours it is hard to imagine that the Turnpike will function much more smoothly, given the roadway’s size and the increase in volume during the five decades since it was built.

Traffic always finds a way of emerging, whether due to solar glare, tight turns, or steep grades, making the financial argument even more important and the financial reality more unfortunate. If the new system won’t save as much as originally claimed, we hope it at least saves us some time and a whole lot in safety risks.

This blog explores the State’s switch to an all-electronic tolling system from a financial perspective. For a more general review of the changes to come please see our full report.