Why Are Tuition and Fees Rising at UMass?

Over the last half-century, college tuition costs have exploded at a rate that far outpaces the consumer price index (CPI). The reasons for this spike in cost vary by type of institution.

For public higher education, the Delta Cost Project, a research institution focused on American higher education, notes the rise is rooted in increases in spending on administration and student support services alongside changes in government funding. These factors are accountable in part for what the Office of Institutional Research at UMass’s flagship Amherst campus has reported to be an inflation-adjusted increase of 84% in tuition costs since 2000. Pioneer’s MassOpenBooks, a transparency application that pulls together and publicizes outgoing payments made by government organizations, sheds light on what drove UMass to charge higher tuitions.

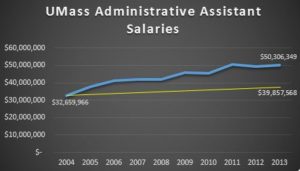

Administration: As the Huffington Post reports, the number of non-academic administrative and professional employees in higher education institutions has more than doubled over the last 25 years, far outpacing student population growth. The UMass system is no exception, as evidenced by the increase in administrators’ wages. The following graph uses MassOpenBooks data to show the rise in the total wages of administrative workers at every UMass campus. It includes the summed wages of the seven most prevalent administrative job titles. Compare the increase to the yellow line representing inflation, based on CPI data.

Administrative costs appear to have come at the expense of instructional cost. As the number of administrators rose, the number of faculty declined. At the Amherst campus alone, according to their own Office of Institutional Research, the number of professors has declined from 595 to 459 since 2000. Over the same span, tenure-track faculty fell from 89% to 80%. Across UMass, MassOpenBooks tells us that, from 2004 to 2013, the number of full-time professors declined by over 25%.

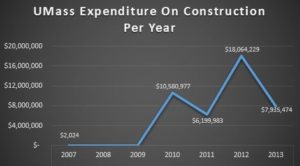

Spending: The fiscal difficulty that has prompted public higher education tuition hikes nationwide has not kept UMass from initiating expensive construction. The following graph uses MassOpenBooks data to represent the UMass system’s construction expenditures from 2007 to 2013. The initial spike in costs coincides with the beginning of UMass Boston’s 25-year “Master Plan” of construction and redevelopment, which the school projects will have cost $750 million by 2017. On top of that, a 2013 MassLive article reported that four new buildings under construction at the Amherst campus would cost over $268 million.

With CollegeBoard, a non-profit that pushes for greater access to higher education, reporting that Massachusetts ranks in the top 10 most expensive states in terms of average in-state tuition at four-year public universities, students and parents alike may question the expansions. As tuitions continue to rise, students in lower-income households are increasingly deprived of the greatest tool for upward mobility. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Economic Mobility Project, of the people raised in the bottom quintile of the family income ladder, 47% of those who do not earn a college a degree remain there as adults, compared to only 10% of those who earn degrees.

In 2008, the New England Association of Schools and Colleges based an in-depth report on UMass Boston using the school’s self-evaluations. The report, occurring during a period of tuition growth, detailed a 25% decrease in full-time equivalent professors, which “caused the University to rely more heavily on teaching assistants and part-time faculty to teach classes, and […] led to some increases in class size”. These effects led to a decline in the “perceived quality of the educational experience the University offers”, despite the higher tuitions. The rising tuition and fees coincided with an 18% decline in headcount enrollment that the report holds was, in large part, the effect of part-time students being priced out of the higher education market.

Government Funding: MassOpenBooks shows that state spending on UMass has stayed rather steady around $550 million annually from 2007 to 2013. In a time of growing college enrollment, this stagnation would indicate less per-student government funding. However, as the Washington Post explains, this is not the case for public research universities. For these schools, federal subsidies and profits from associated endeavors, such as hospitals, have increased enough to more than offset the state fund stagnation, at least between 2000 and 2010. In fact, the increase in revenue was enough, the Post reports, that public research universities could have kept tuition stable and still pocketed $2,651 per student more in 2010 than in 2000.

According to data published by the UMass Office of the President, there was a $1.1 billion, 69% increase in net assets in the five-campus UMass system from June 2008 to June 2014. Over the same span, UMass undergraduate tuition and fees increased by one third, or $3,037. If it had so chosen, UMass could have limited tuition hikes over the span to $750 dollars, one quarter of the actual increase, and still come away with a net increase in assets of more than $100 million over the 6-year period. The office’s 2014 financial report notes that a major component of the net asset increase was “positive operating results due primarily to greater student fee revenues”.

Tuition and fees have been steadily and steeply rising across all institutions of higher learning, though the reasons behind such a rise vary by type of institution. For UMass, they have risen in part because of vast administrative and infrastructure expansions. Is that in the best interest of the system’s students?