The Globe on Common Core and Poetry

It is not stereotyping poets to say that they burn with a particular passion. Just as a biochemist has insatiable curiosity about living organisms, the ways in which genetic information gets stamped into DNA, nucleic acids and lipids, poets have a burning passion for creating worlds, images and associative metaphors and paradoxes with words. They are believers in The Word.

That’s why it may seem so unthinkable for a curmudgeonly poet like Philip Larkin to insist that his diaries be shredded and burned. But of course, that is easily understood given that he likely saw himself as editing out unreadable stuff or at least stuff that others would use to reduce his poetry to “buggery,” as he’d put it. (Well, that and he certainly remembered the novellas he wrote under his female persona/pseudonym of Brunette Coleman.)

Harder to understand perhaps is Gerard Manley Hopkins’s decision to burn his poems—all but a few that Robert Bridges was able to get his hands on—as he joined the Jesuit novitiate. A higher burning passion indeed. And a profoundly sad one for us.

In an age when most K-12 education policy is crafted in the image of the dead language of edu-jargon, rather than the highest aspirations we have for our kids, I know that poetry (outside of a slam competition here and there) won’t make it to the policy wonk’s dance card, nor even to the checklist of program officers at foundations started by very well-meaning philanthropists.

But Massachusetts did not build its reforms based primarily on closing the achievement gaps. That would be akin to assuming that our suburban schools were high-performing and that whites and Asian-Americans were learning at acceptable levels. It would mean that there were plateaus (limits) we should expect African-American, Hispanic and immigrant populations to reach—and that we should stop expecting more of them given that reality.

When one of the principal drivers of the state’s landmark Education Reform Act, Tom Birmingham, spoke of his vision for Massachusetts’ schools, it was based on his own experience as a kid growing up in Chelsea, attending Harvard College and later as a Rhodes Scholar. His view was that his classmates in Chelsea deserved access to a high-quality liberal arts education every bit as much as did the schoolchildren in Wellesley.

It was a vision that meant that, yes, we would lift all boats and that kids would come into contact with, yup, some rote materials. But it also aimed to require content materials that featured puzzlingly complex uses of words and could inspire a child to think (even if only fleetingly) about the human condition.

In commissioning The Dying of the Light: How Common Core Damages Poetry Instruction, Pioneer had in mind just that – the different intellectual visions driving our state reforms, on the one hand, and the Common Core, on the other.

The report includes a detailed case study of the texts and themes recommended by a Common Core consultant for a Common Core-based literature unit, as well as a broader analysis of Common Core’s poetry offerings. The conclusions are that

- A dramatic reduction of time spent on classical literary texts implicitly mandated by the national standards will also reduce the emphasis on timeless poetry.

- The paucity of poetry included in Common Core and the incoherent list of poems in an appendix leaves poetry in a precarious position in any local curriculum and gives teachers little guidance about the poems’ relative complexity or quality.

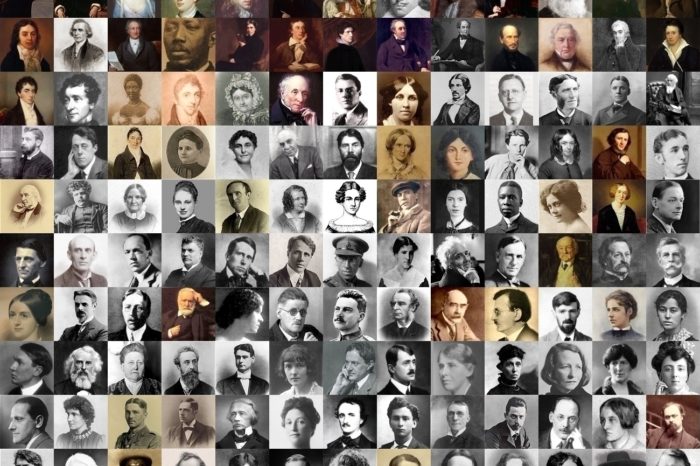

- The shrinking role of poetry in public schools is particularly troubling in Massachusetts, a state whose poets form such a large part of our national literary heritage. (Massachusetts is the home of Emily Dickinson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and many US Poets Laureate, Pulitzer Prize- and Nobel Prize-winners.

The report drew front-page coverage in the Boston Globe, with journalists Kathleen Burge and Maggie Quick providing a balanced yet nuanced report on the impact of Common Core on poetry instruction. While gaining perspective from Massachusetts Education Commissioner and teachers, the reporters caught the key points as to why implementation of the Core will adversely impact the study of poetry in the classroom and ultimately student achievement:

“Even if Massachusetts adds more poetry to its standards, teachers will be less likely to teach it, since it will not appear on the national tests,” said Jamie Gass, director of the institute’s Center for School Reform.

“The quality of the vocabulary found in classical literature, poetry, and drama is just much higher than what Common Core offers through informational text and nonfiction,” he said.

A Boston Globe editorial this weekend disagreed with our study, oddly beginning a piece on poetry instruction by labeling Pioneer “libertarian.” (The front-page Globe story offered another label so the paper may want to get on the same page with their descriptions.) The problem with such a “political” framing for an editorial is that I don’t believe any of the co-authors would describe themselves as libertarian. And I doubt that their interest in poetry has anything to do with politics—two are highly respected academicians, one a long-time 8th grade English teacher.

Anthony Esolen, a poet and professor of literature at Providence College, who between 2002 and 2005 translated the three volumes of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy for the Modern Library. He is the editor and translator, again for the Modern Library, of Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things and Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered. See far below recent longer piece by Esolen on Common Core/poetry, etc. Priceless lines.

Jamie Highfill, for 11 years an 8th grade English teachers in Arkansas and the Natural State’s 2011 Middle School English Teacher of the Year. In a Washington Post piece on the Core (http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/common-core-state-standards-in-english-spark-war-over-words/2012/12/02/4a9701b0-38e1-11e2-8a97-363b0f9a0ab3_story.html), it was noted that

Jamie Highfill is mourning the six weeks’ worth of poetry she removed from her eighth-grade English class at Woodland Junior High School in Fayetteville, Ark. She also dropped some short stories and a favorite unit on the legends of King Arthur to make room for essays by Malcolm Gladwell and a chapter from “The Tipping Point,” Gladwell’s book about social behavior.

“I’m struggling with this, and my students are struggling,” said Highfill, who was named 2011 middle school teacher of the year in her state. “With informational text, there isn’t that human connection that you get with literature. And the kids are shutting down. They’re getting bored. I’m seeing more behavior problems in my classroom than I’ve ever seen.”

Sandra Stotsky, who from 1991-97 was the editor of Research in the Teaching of English, published by the National Council of Teachers of English. She was also in charge of developing and revising Massachusetts’ 2001 English Language Arts Curriculum Framework.

These are people who know their stuff. In The Dying of the Light, Esolen describes why poetry is critical to the full realization of a child’s humanity; Highfill describes the three-part process by which poetry has traditionally been taught in American schools. Stotsky traces the history of the poetry curriculum in this country’s public schools.

But the Globe editorial actually goes down from there.

But the Common Core doesn’t set curriculums, and there is nothing stopping districts from building their own programming on top of the federal standards. In fact, Massachusetts did just that by adding the writing of poetry into the state curriculum and by folding in the list of recommended poets the Commonwealth created back in 2004. Ensuring that poetry gets taught in public schools is the responsibility of local school districts, just as it was before the Common Core.

The Globe editorial, written by Noah Guiney, is buying two arguments here: First, that states can add as much state-specific (non-Common Core) material as they want into their own versions of the Core and their local curricular interpretations of the Core. I’ve encountered this argument in many states around the country, especially when state superintendents or commissioners of education are trying to evade legislators’ questions. (In Utah, former state superintendent Larry Shumway lost his job for repeatedly telling legislators that they would add 40%, even 50% more state-specific content to their version of Common Core.) Proponents often try to rebut our view that the Core actually provides little flexbility with trite statements like “there are no Common Core police.”

It is true that Common Core is not a curriculum — in a very technical sense. A technical sense because there are, in fact, a good number of highly specific standards, e.g., early-grade math standards that impose curricular choices in terms of math methodology, high school geometry curricular paths, and more. In addition, the applications from the two testing consortia (PARCC and SBAC) to the USED for federal funding include in them explicit recognition that they will be developing curricular materials and instructional practice guides. (By the way, that’s in violation of three federal statutes, but I digress.) But the larger point to make regarding how prescriptive the Core is gets to the second argument that Guiney is buying.

Guiney seems to believe that academic standards are purely theoretical. He completely glosses over the existence of Common Core-aligned tests and teacher evaluation systems. While it is true that standards do not drive specific curricular choices when they are not tied to a test, that is not the world that we live in. With Common Core -aligned tests, such as PARCC or SBAC (and Massachusetts is to be part of PARCC), the only material that will be tested is to be found in the Common Core standards. To be clear, the PARCC test will not test state add-ons, whether poetry, classic literature, Euclidian geometric concepts, trigonometry or pre-calculus. The add-ons are at best of minor influence in the early years of implementation; after a couple of years, as tests and accountability measures take hold, they will be of paltry little influence. That is even more so as the teacher evaluations, which are in part built on student performance on the PARCC (or SBAC) test, take hold.

Teachers will indeed teach to the test. It is in their self-interest. As Margaret Spellings used to say, “you measure what matters.” And then there is the corollary effect: What you measure matters. It is what gets teaching emphasis. And with that, the poetry add-ons will go. Math beyond Algebra II will go except in the wealthy districts, etc.

By accepting these arguments, Guiney is making a claim of his own: He is implicitly claiming that superintendents, principals and teachers are going to spend class time on things that aren’t on the PARCC test. He is claiming that they will spend time on the add-ons even when teacher evaluations – and possibly employment – are premised on improvements on test scores. And why would they do that? Is it because they have the best interests of the students at heart? Perhaps because they are courageous innovators? In the real world, self-interest and career advancement will trump poetry.

The only places where teachers will still teach high-quality liberal arts content with a strong offering of classical poetry are the wealthiest communities and prep schools like Milton Academy. And the reason is that they have a higher accountability than to tests – they see themselves as getting kids into elite schools.

For parts of the Bay State where there is less accumulated wealth and where not every kid aims at an Ivy League school, expect less literature and expect less poetry. This is the undoing of Tom Birmingham’s vision of education, which was again that kids in Chelsea deserve access to a high-quality liberal arts education every bit as much as do the kids in MetroWest’s “W” communities.

We’ve seen so many fads in American education over the decades. Birmingham’s was the only vision that actually moved the needle strongly in the US. It’s unfortunate that the Globe is blind to that.

Follow me on twitter at @jimstergios, visit Pioneer’s website, or check out our education posts at the Rock The Schoolhouse blog.