Problem: Overpriced Textbooks, Solution: Opensource Material

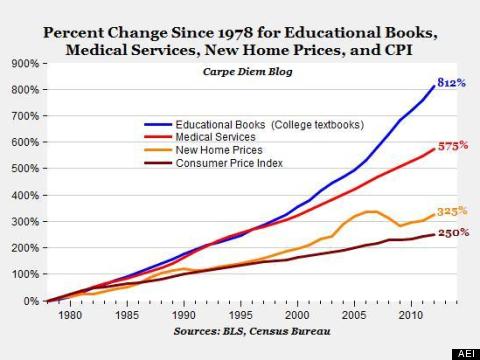

Last week, NBC news announced that textbooks prices have risen 1,041% since 1977, three times the rate of inflation according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As if tuition costs weren’t already exorbitant. For the 2014-2015 academic year, the average private four-year college tuition in Massachusetts was $34,643, which does not include the average room and board of $11,181.

Even the UMass price-tag is a stretch for working-class families; UMass Amherst, for example, estimates 2015-2016 tuition fees at $14,171.

Surprisingly, textbook price increases have outpaced even the 559% increase in college tuition and fees over the past three decades. Even more problematic is that textbook prices, unlike tuition, are not factored into the Expected Family Contribution (EFC) calculated by the U.S. Department of Education to inform colleges’ financial aid offices. Thus, students are largely left on their own to scour the web for books to rent or track down upperclassmen for used books.

Though renting textbooks is a less-expensive alternative, it prevents students from selling the rented book back to the bookstore or another student at the end of the year. Another popular option is negotiating with upperclassmen for used books. In this instance, social media functions as a commercial market, connecting sellers and potential buyers via posts in private “Class of 201_” groups.

Textbook publishers, well aware of the losses they will incur if students share books rather than purchase new ones, release new editions at an average of every 3.9 years, according to a study completed by the California State Auditor in 2008. Professors admit these textbooks rarely contain large differences, but alterations in page and problem numbering cause issues when students attempt to complete assignments with old editions.

New editions also cause problems with book buyback programs. At college bookstores, like those of UC Davis and CSU Sacramento, students can attempt to sell the book back for 50% of its retail price. If next year’s class requires a new edition, though, the student is out of luck. Not only will the bookstore not be interested, but underclassmen will have no need for the book either.

At UMass Dartmouth, students who receive “excess financial aid” may apply for a Textbook Voucher of $400 per semester. Neither eligibility requirements nor how many students actually receive “excess financial aid” are listed online.

UMass Amherst advertised a book buyback program on its Facebook page at the end of the fall 2011 semester, a student commented: “will they actually be fair buyback prices this time? (instead of 20% of the actual cost of the book like last year)”. The store replied with a link to its main page, inviting students to “like” the store. Students liked the complaining comment instead.

To combat the textbook issue, UMass Amherst teamed up with Amazon to refashion its Textbook Annex into an online store for fall of 2015, with a predicted savings of $380 per student annually.

The best idea yet, though, may be to move away from textbooks completely. UMass Amherst started the Open Education Initiative five years ago, which offers faculty grants ranging from $1,000 to $2,500 to convert from textbook to open source material. Over 30 faculty members have reworked their courses to correspond with freely available online information, saving students over $1 million in course materials.

If more colleges follow UMass Amherst’s lead, the textbook industry will be forced to drastically decrease its prices if it is going to survive. So far, it has enjoyed, and exploited, dominance in an anti-competitive market.

66 percent of college students in Massachusetts already took on debt in 2013 with a slightly higher-than-national-average rate of $28,565. Clearly, they cannot afford to pay more for their textbooks. Yet, at a 27.4% annual price increase, it is clear that textbook prices are not going to come down out of concern for students who are already in the red.

It’s time for local government to encourage more college administrations to partner with faculty in providing affordable course materials for students so they can focus on learning instead figuring out how to pay for books.