How has COVID-19 impacted the MA opioid crisis?

In recent years, Massachusetts has seen a much larger uptick in opioid-related deaths than the national average. The state witnessed opioid overdose-related deaths rise by 41.6% between 2013 and 2014, with Barnstable County constituting 32.5% of the total increase. As identified by Harris Foulkes of Pioneer Institute, the opioid crisis on Cape Cod can be attributed to an opiate prescription rate that is 24% higher than the state average.

In response to the opioid crisis, a prescription monitoring program was launched in 2016. The program tracks prescriptions by patient and includes information on drugs prescribed, the prescriber, and the pharmacy. This allows doctors to monitor the drug consumption patterns of patients and inform law enforcement agencies if they believe a patient has been seeking opioids for non-medical purposes. As a result of the program, opioid prescriptions went down by 25% in 2017. In the first nine months of the same year, the cases of fatal opioid overdose declined by 10%.

However, this success was reversed by the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the most considerable spillover effects of COVID-19 has been a spike in opioid use and overuse. For instance, opioid overdose cases rose by 5% in Massachusetts in 2020, marking the first increase since 2018. The state department of health reported a 2% increase in drug overdose deaths for the first nine months of 2020, compared to 2019. It is imperative to note that during the first nine months of 2020, COVID-19 was raging across the country, compelling citizens to observe social isolation. Dr. Miriam Komaromy of the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center states that uncertainty brought by COVID-19 increased stress levels for the population, which often serves as a trigger for drug use. She also says that people consumed drugs alone due to the COVID-19 social distancing policies, increasing the likelihood of overdose.

Michael Barnett, assistant professor of health policy and management at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, agrees. He states that during times of global upheaval, especially during a pandemic, the financial and social stressors brought on by the loss of a job or social connection trigger the psyche, compelling people to initiate opioid use or turn back to older addictions.

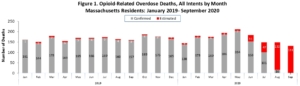

The figure shows month-by-month instances of opioid overdose instances from January 2019 to September 2020 (Source: Massachusetts Department of Public Health)

Just like COVID-19, its spillover effects affected various population groups differently. Fo14r instance, among racial and ethnic groups, Black non-Hispanic men were more likely to fall victim to opioid addiction. In Massachusetts, public health officials reported that Black men died of a drug overdose in 2020 at a rate 69% higher than in 2019. To put this in perspective, this means that deaths from overdose among Black men jumped from 32.6 per 100,000 in 2019 to 55.1 in 2020.

Even before the pandemic, poverty, job loss, and lack of access to healthcare facilities affected black communities disproportionately. The pandemic only exacerbated it. During the pandemic, members of the Black community were more likely to be hospitalized and die of COVID-19. This, combined with the loss of income and social security, brought in added stresses and fears, which resulted in an increase in drug use amongst them.

COVID-19 exacerbated the risks of opioid overdose for Massachusetts residents. What can be done in response to this? Michael Barnett suggests getting rid of the “X-waiver” which requires physicians to obtain a special waiver from the Food and Drug Administration to prescribe medication used to treat the opioid disorder. Often, it is difficult to get the waiver, and therefore, doctors cannot directly assist the patients in combating opioid addiction. He also suggests investing in counseling services. Usually, a history of stress, anxiety, and depression triggers a brain response that leads to opioid use and abuse. Therefore, tackling the root cause can help resolve the problem in some ways. It is also imperative that monetary resources are dedicated to combating the epidemic. For instance, when Massachusetts received $55 million in 2018 to combat the crisis, the following year saw opioid overdose cases decrease by 6%.

While these policies are not exhaustive, they are necessary to make progress in the right direction and tackle the epidemic of opioid overdoses in Massachusetts.

Maida Raza is a rising Senior at Earlham College. She is pursuing a Bachelors’s in Economics and Mathematics. Maida is working as a MassEconomix Intern at Pioneer Institute.