Examining the New Massachusetts Estate Tax

In October of 2023, Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey signed H.4104, “An Act to improve the Commonwealth’s competitiveness, affordability, and equity.” The bill makes several changes to tax law in Massachusetts, including an amendment to the estate tax.

The New Law

The change increases the estate tax exemption from $1 million to $2 million, meaning only estates valued over $2 million are subject to the tax. The change also eliminates the ‘estate tax cliff,’ as the new tax only applies to the portion of an estate that exceeds $2 million rather than the entire estate. For example, if an estate is valued at $3 million, only the $1 million that exceeds the $2 million threshold will be subject to the tax. Previously, if an estate was valued at over $1 million, the entire estate was taxed. Despite the fact that the tax was changed in October 2023, the change was retroactive, as it impacted estates dating back to January 1st, 2023.

Less Revenue

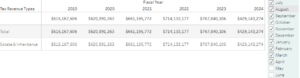

Using Pioneer Institute’s MassOpenBooks data transparency tool, it is clear that there has been a drop in estate tax revenues. Complete data are not yet available for fiscal year 2024, but for the months of July to April, Massachusetts collected over $429 million in estate taxes. This was a significant decline from the same period in fiscal 2023 ($750 million) and fiscal 2022 ($715 million). It’s too soon to tell how much of the drop was related to the tax law change, but some level of decline may have been expected from lawmakers.

Broader Issue

The increased exemption and elimination of the estate tax cliff were not the only changes to the estate tax. Another change that pertains to out-of-state property has received attention due to its legal implications as opposed to its economic impacts, as some have said that the inclusion of out-of-state property in estate tax calculation is unconstitutional.

Under the new law, the estate tax takes into account ‘real property’ located outside of Massachusetts that is owned by an estate. For example, if somebody passes away who owned a vacation home in New Hampshire, the home is now included in the estate for purposes of calculating estate tax liability. So if the house was worth $1 million, but the rest of the estate was valued at $1.5 million, the estate would surpass the $2 million threshold. Previously, out-of-state property was not included in Massachusetts’ estate tax calculation.

Despite the fact that the total tax would be reduced in proportion to the value of assets located outside Massachusetts, some lawyers believe this element of the law is unconstitutional. Supreme Court precedent points to the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment as prohibiting states from collecting taxes on property located in other states. This may call the constitutionality of the Commonwealth’s estate tax law into question.

Although the tax law change may be contributing to a reduction in the amount estates pay in taxes, it may be reasonable to expect revenues to decrease further if legal challenges are successful. Even after reform, Massachusetts still has one of the nation’s most onerous estate taxes. Most states do not even have an estate tax. Without more serious attempts at reform, the financial incentives may cause more older individuals and retirees to leave the state, especially as families consider the effect of including out-of-state property as part of their total tax liability.

About the Author

Matt Mulvey is a Roger Perry Transparency Intern at the Pioneer Institute. He is a rising senior at Swarthmore College where he is a political science major and history minor.