“[B]y making the power of the Senate a sort of ballast for the ship of state and putting her on a steady keel, it achieve[s] the safest and the most orderly arrangement…”

– Plutarch, Greco-Roman historian, first-century A.D.

In Pioneer’s ongoing series of blogs here, here, here, and here on curricular resources for parents, families, and teachers during COVID-19, this one focuses on:

Celebrating the U.S. Senate

“The use of the Senate is to consist in proceeding with more coolness, with more system, and with more wisdom, than the popular branch,” wrote James Madison, the “Father of the Constitution.” In many regards, the U.S. Senate is the essential institution under the republican form of government.

The Founding Fathers designed the Senate to be a deliberative body that serves as a balancing force between the executive powers of the presidency and the more popular passions of the U.S. House of Representatives. In our federal government, the role of the Senate is to fully represent the often neglected rights and interests of the states.

The Roman republic provided the template for the Senate. In fact, the word “Senate” is derived from the Latin “senatus,” which means “council of elders.” That is what our Framers had in mind. Each state – regardless of population – has two senators who serve six-year terms. It wasn’t until passage of the 17th Amendment in 1913 that senators were popularly elected. Before then, they were chosen by state legislatures.

The Senate’s Golden Age was the 1830s and ‘40s when the body was dominated by three senators who came to be known as the “Great Triumvirate.” Henry Clay of Kentucky the “Great Compromiser;” Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, the “Great Orator” and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, the “Cast-Iron Man,” were all distinguished orators and parliamentarians. Each was also appointed U.S. secretary of state, but in the Senate they battled over historic issues like slavery, protective tariffs for industries, and states’ rights.

As the elder statesmen of the American republic, senators have a number of powers that House members don’t. These include approving foreign treaties before ratification, as well as confirming the executive appointments of Cabinet secretaries, military officers, ambassadors, U.S. Supreme Court justices, and other federal judges.

Even still, it’s been decades since anyone can recall a memorable speech delivered by a U.S. senator. The U.S. Senate’s vital, though sometimes dormant, authority in the face of the Imperial Presidency means few Americans and schoolchildren truly understand its constitutional role and inner workings. To remedy this, we’re offering a variety of resources to help parents, teachers, and high schoolers:

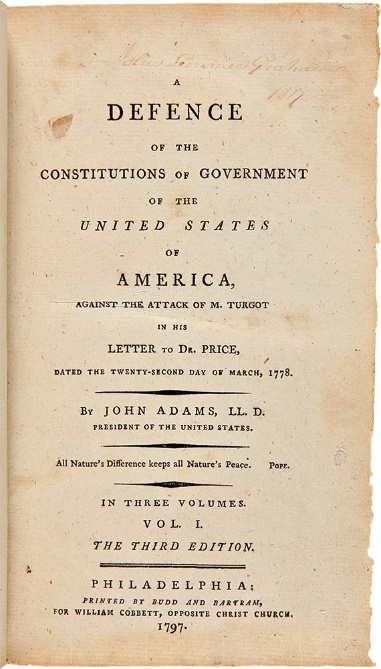

A Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America (1787-88), by John Adams

The Virginia Plan (1787), by James Madison

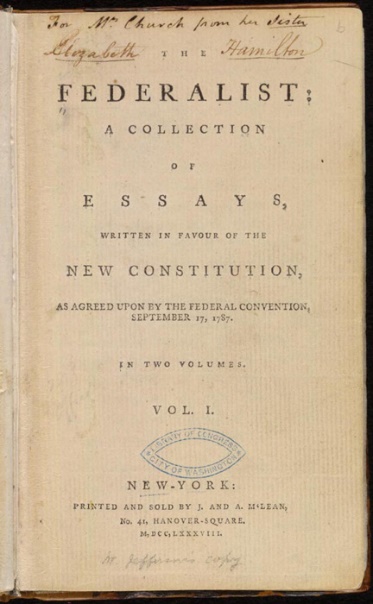

The Federalist Papers: No. 62 (1788), by “Publius” James Madison

The Constitution of the United States, Article. I. Section. 3., The National Archives

A Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States, by Thomas Jefferson

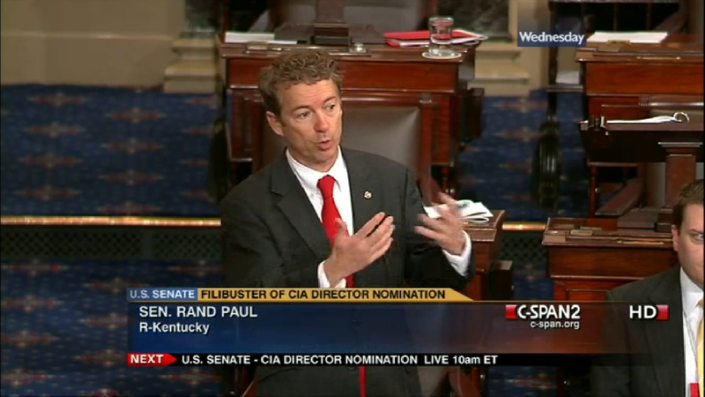

The Filibuster in the United States Senate

Thomas H. Benton (American Statesmen Series), by Theodore Roosevelt

The Webster-Hayne Debate on the Nature of the Union: Selected Documents, by Herman Belz (Editor)

The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, and Calhoun, by Merrill D. Peterson

John C Calhoun: A Biography, by Irving H. Bartlett

Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time, by Robert V. Remini

Henry Clay: The Essential American, by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler

America’s Great Debate: Henry Clay, Stephen A. Douglas, and the Compromise That Preserved the Union, by Fergus M. Bordewich

Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union, by Robert V. Remini

Stephen A. Douglas, by Robert Walter Johannsen

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates: The First Complete, Unexpurgated Text, by Abraham Lincoln & Stephen A. Douglas, Harold Holzer (Editor)

Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War, by David Donald

The Great Speeches and Orations of Daniel Webster: With an Essay on Daniel Webster as a Master of English Style, by Edwin P. Whipple (editor) and by Daniel Webster (author)

The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War, by Stephen Puleo

The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation, by Brenda Wineapple

Classic Senate Speeches, United States Senate

The Road to Mass Democracy: Original Intent and the Seventeenth Amendment, by C. H. Hoebeke

The Senate and The League of Nations, by Henry Cabot Lodge

Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer, by Nancy C. Unger

Arthur Vandenberg: The Man in the Middle of the American Century, by Hendrik Meijer

Mr. Republican: A Biography of Robert A. Taft, by James T. Patterson

Everett Dirksen and His Presidents: How a Senate Giant Shaped American Politics, by Byron C. Hulsey

Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy, by Larry Tye

Politics of Conscience: A Biography of Margaret Chase Smith, by Patricia Ward Wallace

Master Of The Senate: The Years of Lyndon Johnson, by Robert A. Caro

JFK in the Senate: Pathway to the Presidency, by John T. Shaw

Goldwater: The Man Who Made a Revolution, by Lee Edwards

The Senator and the Sharecropper: The Freedom Struggles of James O. Eastland and Fannie Lou Hamer, by Chris Myers Asch

Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon, by Larry Tye

Bridging the Divide: My Life, by Edward Brooke

The Last Great Senate: Courage and Statesmanship in Times of Crisis, by Ira Shapiro

The Senate 1789-1989 Addresses on the History of the United States Senate (4 volumes), by Sen. Robert C. Byrd

The Senate of the Roman Republic: Addresses on the History of Roman Constitutionalism, by Sen. Robert C. Byrd and the Senate Historical Office

The Breach: Inside the Impeachment and Trial of William Jefferson Clinton, by Peter Baker

The American Senate: An Insider’s History, by Neil MacNeil and Richard A. Baker