Why Study History?

Why study history?

Because the Founders asked us to — and because it’s good for you.

Ben Franklin’s quip after the Constitutional Convention that he gave Americans “a republic if [they] can keep it” is an oft-repeated line in civic-minded circles, but the sentiment expressed is no less relevant.

Our most senior Founding Father understood the sensitivity of the new American experiment. He hoped future citizens would study the historical narrative and intellectual reasoning that informed our Constitution. Otherwise, its soaring rhetoric would be little more than a “parchment guarantee” to those unfamiliar with how America arrived at more enlightened governance.

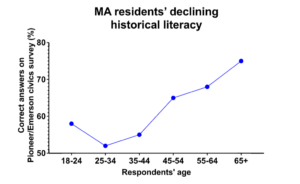

Almost 250 years later, Franklin’s warning remains prescient. History aptitude among voters today is woefully inept. Massachusetts residents cumulatively scored an average of 63 percent on a recent Pioneer/Emerson College survey that asked questions based on the U.S. citizenship exam.

That Massachusetts’ youngest voters scored worse than their older counterparts is worrying for our future republic. It is also unsurprising, given record low standardized test performance across the country.

History enthusiasts and educators may see these figures and lament young people’s ill-preparedness to meet the duties of their citizenship. But the poll also found that young people who had studied more history and civics in grade school had higher scores, closer to those recorded by the average voter.

The correlation between exposure to history and better performance on a test or poll should be of some comfort. It illustrates that students haven’t forgotten how to digest and comprehend historical facts when presented with them.

Cultivating interest in history and civics studies in a generation obsessed with TikTok poses a real challenge. But amidst broad declines in knowledge and aptitude, the discipline is as relevant as ever to today’s political discourse.

Historical arguments about America’s Founding and subsequent legal evolution stir passions with both the political right and left. The enduring legacy of our Constitution is cited as both a catalyst and inhibitor of discord. Whatever their ideology may be, Americans today aren’t simply invited to participate in debates over the nation’s history — in many cases, they can hardly avoid participating in such discussions. History education should arm them with the knowledge they need to participate in an intelligent and civil manner.

Pioneer’s new book, Restoring the City on a Hill: U.S. History and Civics in America’s Schools, outlines the background and challenges of K-12 history and civics education. Its pages hold lessons from some of the wisest thinkers and statesmen on the importance of studying history, and why historical knowledge is so important to building individual political acumen in our fervently ideological moment.

Restoring the City on a Hill quotes Winston Churchill’s reminder that “in history lie all the secrets of statecraft.” The book includes Thomas Jefferson’s similar line about how history’s appraisal of past events and developments made its practitioners better and more sober judges of the future. James Madison features a less lofty but no less valid interpretation: A nation with no “popular [historical] information” was a “prologue to a farce or a tragedy.”

For these architects of Western, democratic government, a deep historical knowledge was crucial to understanding the process by which representative democracies formed, and the maintenance they required to avoid implosion.

Churchill and the Founders make a strong case for studying history, especially for older citizens — those long out of school — who could still benefit as voters and political actors. Yet our society too often fails to address the problem of declining interest and engagement among K-12 students. They are put off by facts and descriptions of a time they mistakenly see as irrelevant to the present.

Parents, educators, and policymakers need to refute this myth of history’s irrelevance and show instead that the opposite is true.

America’s uniquely constructed bicameral legislature and independent federal judiciary aren’t just mundane constitutional provisions recorded as stale facts in a textbook. They are vivid textual reminders of the inequitable political environment under the British Crown, the physical struggle to end British subjugation, and the subsequent intellectual struggle of America’s Founders to build a more representative union with effective governance lasting through today.

Not only does constitutional history demand our attention in today’s politics, but as Americans we owe our forefathers the responsibility of ensuring that citizens of all ages remain interested in the nation’s past.

So, reader, don’t sit idly by while lamenting the decline of history as an unfortunate but unavoidable circumstance. Uphold the Founders’ charge and take the initiative to improve your and your loved ones’ historical literacy.

· Visit the National Constitution Center’s interactive webpage to explore all seven articles and 27 Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

· Support organizations such as We The People, which sponsors a national essay contest on history and civics knowledge that has helped almost 30 million students become more acquainted with the Founding Era.

· Parents should consider extracurricular programs for their children that promote civic engagement, such as Teach Democracy’s annual high school mock trial program, which inspired this author’s passion for history, law, and policy.

Whether you’re young or old, lean left or right, or live in a blue state, red state, or one in the middle, do read and study history. Do so for the love of knowledge, to better understand how our nation came to be, and so that we might preserve the republic that Ben Franklin and other Founders bequeathed to us.

Jude Iredell is a Roger Perry Civics Intern with the Pioneer Institute. He is a senior at Pomona College pursuing a degree in history.