States across the country have enacted eviction moratoriums. What does this mean for the housing market in the long-term?

Last week, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed a bill into law that essentially suspends the state’s eviction and foreclosure processes for the remainder of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tenants’ rights and housing advocates largely viewed the measure as much-needed stabilization for the economy at a time when the country is likely facing a hard recession. Proponents believe that failing to provide a safety net for renters and homeowners alike would likely prolong the recession and aid the spread of the virus.

Still, property owners and real estate industry spokespeople have warned of the ripple effects of foregone rent payments once the eviction moratorium is lifted. At that point, the judicial system will likely face a backlog of eviction cases, leading to further delays in rent payments that could push landlords to the brink.

While squeezing property owners financially may seem like a better outcome than forcing thousands of tenants onto the streets, some observers think Massachusetts’ legislation could have been better designed to accommodate the needs of property owners. Unlike the state’s mid-March court order, the new legislation prevents landlords from issuing “notices to quit,” which start the eviction process without immediately mandating that anyone vacate the property. Some states, such as Connecticut, momentarily made use of this distinction by pausing eviction-related court proceedings while still allowing landlords to file new eviction cases. While an executive order from Connecticut’s Governor later changed this policy, the state still makes stalled rent payments and other benefits contingent on proof that the inability to pay rent is a result of COVID-19.

Yet many housing advocates are unsatisfied with this middle ground, suggesting that an eviction notice would convince many tenants to leave their homes anyway, regardless of the lack of legal repercussions. With an absence of tools left to hold tenants accountable for rent they are still able to pay, landlords have worried that these moratoriums will simply transfer their tenants’ burdens onto them. New Hampshire’s Attorney General even published a memo asserting that tenants will be required to pay all the rent they owe after that state’s moratorium expires, and also that the moratorium has substantial exceptions – in cases of domestic violence, for example. New Hampshire is one of the few states that has paused “every step of the [eviction] process” as part of its moratorium.

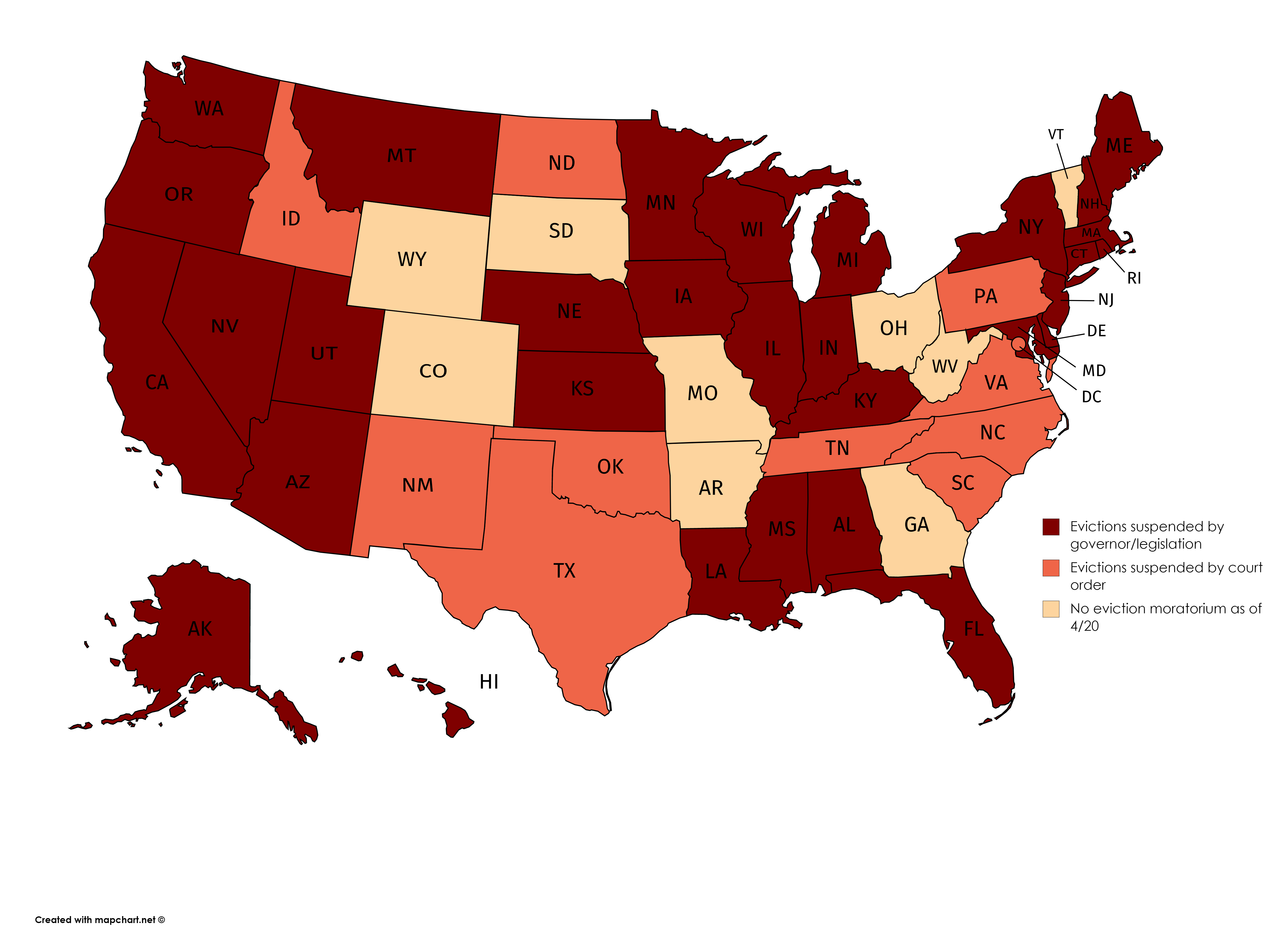

Meanwhile, Vermont is the only northeastern state without an eviction moratorium as of April 20th after a legislative effort stalled in the state House of Representatives (see Figures 1 and 2). Perhaps it’s not a coincidence, then, that Vermont also has the second-highest homeownership rate in the country after West Virginia. The flip side is that in renter-heavy New York, there’s enormous political pressure to prioritize financial relief for tenants over all else.

Figure 1: Map of eviction moratoria issued in response to COVID-19 by state

Sources: Ballotpedia, Law Newz Inc., Millionacres, National Consumer Law Center, National Low Income Housing Coalition, NOLO, Stinson LLP

Figure 2: Table of eviction policies under COVID-19 moratoria among northeastern states

| Name of State | Homeownership rate | Eviction Moratorium? | Moratorium Start Date | Moratorium End Date* | Notice of Eviction Allowed? | Required to Pay Back Rent After Pandemic? | Property Owner Foreclosure Delay? | Foreclosure Delay End Date |

| Connecticut | 65.8% | Yes | April 10 | June 1 | No | Yes | Yes | June 2 |

| Maine | 71.2% | Yes | April 16 | 30 days after SOE ends | No | Yes | No | N/A |

| Massachusetts | 61.8% | Yes | April 22 | August 18 or 45 days after SOE ends | No | Yes | Yes | August 18 or 45 days after SOE ends |

| New Hampshire | 71.3% | Yes | March 17 | End of SOE | No | Yes | Yes | End of SOE |

| New Jersey | 64.0% | Yes | March 19 | 60 days after SOE ends | Yes | Yes | Yes | 60 days after SOE ends |

| New York | 53.7% | Yes | March 22 | June 20 | Yes | Yes | Yes | June 20 |

| Pennsylvania | 68.6% | Yes | April 1 | April 30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | April 30 |

| Rhode Island | 61.8% | Yes | March 19 | April 17 | No | Yes | Yes | April 17 |

| Vermont | 72.2% | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

Sources: Ballotpedia, Millionacres, National Consumer Law Center, Stewart Title Guarantee Company

* SOE refers to the jurisdiction’s declaration of a state of emergency

As COVID-19 is pitting the immediate needs of the masses against the looming fiscal woes of cities and states, the real estate industry still has long-term needs and pre-existing problems. Some observers are concerned that failing to protect property owners could result in widespread abandoned housing and disinvestment in already vulnerable communities. Others point out that tenants might be able to evade ever paying their rent during the COVID-19 crisis by simply moving out after the moratorium is lifted. While the Massachusetts bill delays the foreclosure process for up to six months, mortgage loan defaults would likely still result if tenants leave before the eviction process can catch up to them.

Moreover, the legislation passed last week is a stop-gap solution to an already out-of-whack Massachusetts housing market. The state needs to increase the supply of housing much faster than it has been doing to meet demand and keep prices stable, which will only become harder to do if landlords cannot afford to keep their properties. Much like evictions in general, defaults on loans for rental properties would likely have a disproportionate impact on communities that are poorer and more diverse than the state as a whole, given the demographics of renters. As the Massachusetts moratorium’s August 18 expiration date approaches, additional legislative action is needed to stabilize the housing market for the long term.

Andrew Mikula is the Lovett & Ruth Peters Economic Opportunity Fellow at the Pioneer Institute. Research areas of particular interest to Mr. Mikula include urban issues, affordability, and regulatory structures. Mr. Mikula was previously a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern at the Institute and studied economics at Bates College.