State, Regional, and National Employment Trends Point to an Aging Workforce: Part One

Since 2000, the Massachusetts workforce has grown increasingly older. In fact, the number of workers 65 years or older increased 41.3 percent between 2007 and 2021, as only 14.8 percent of that population was employed in 2007 while 20.9 percent were working by 2021.

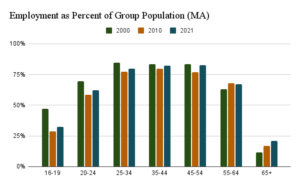

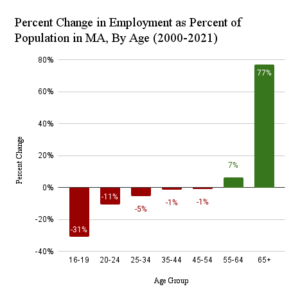

However, employment trends among the oldest demographic of workers are not solely responsible for the aging of the workforce, as declining labor participation from younger age demographics are also partly to blame. Every age category younger than 55 experienced a net decrease in employment as percent of the population between 2000 and 2021, while the 55-64 year old age group saw a 6.52 percent increase and the 65 and older population saw a 77.12 percent increase during those same years.

Fig. 1. Data Source for Analysis: Labor Analytics and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Fig. 2. Data Source for Analysis: Labor Analytics and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

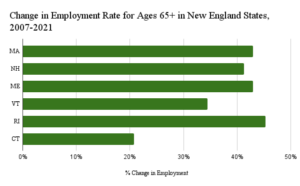

This trend is not unique to Massachusetts. The American workforce by and large has become older in recent years. Between 2001 and 2021 the median age of the labor force grew from 39.6 to 41.7. New England has largely mirrored these national trends. Every New England state except Vermont and Connecticut saw an increase of 40 percent or more in the employment of workers aged 65 and older between 2007 and 2021. Evidently, there has been vast growth over the past 15 years in the number of employed Americans aged 65 or older throughout New England and the United States.

The aging of the workforce is partly due to the Social Security Amendments of 1983, which were passed in response to the increased expected duration of retirement as a result of both increased longevity and earlier retirement. A key change in these amendments was to raise the age at which an individual can retire and receive full retirement benefits from 65 to 67 by 2027. If an individual chooses to retire at 62, the earliest retirement age, they will see benefits reduced by as much as 30 percent. Therefore, many within the 65 and older population are choosing to work longer to maximize the benefits they will be eligible for, while continuing to earn their salaries.

Fig. 3. Source: Labor Analytics (2007-2021)

The amendments also allowed for an increase in the delayed retirement credit (DRC) between 1990 and 2008 from 3 to 8 percent per year. These credits may accrue until the individual is 70, and the overall value of expected benefits over one’s lifetime remains the same despite the delay in receiving them, given an average life expectancy. So this change encourages individuals to work longer, as they can continue to earn their salaries and accrue DRC until they are 70 without losing any retirement benefit value.

Another factor that could have affected the aging workforce is the loss in retirement savings that many retirement or near-retirement age people experienced during the Great Recession. Between the initial stock market crash in 2008 and the lowest point of the downturn in the first quarter of 2009, the nation’s retirement accounts, such as 401(k)s and IRAs, lost about $2.7 trillion, or 31 percent of their peak value in 2007 before the crash.

As a result, while men and women aged 62-64 saw elevated unemployment rates, these demographics also had an increased labor force participation rate during the recession. According to the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, during and following the Great Recession “…older displaced workers appear[ed] more likely than those in previous recessions to remain in the labor force and search for jobs instead of immediately retiring. This trend may reflect growing unease about retirement income security.” Because of the losses suffered to retirement funds in 2008, many who were eligible for early or full retirement were discouraged to retire and instead sought new employment to delay it, which has in turn caused the workforce to become older.

Additionally, inflation has caused the prices of goods and the cost of living to soar, making it more challenging for those living off fixed retirement benefits to afford basic necessities in many cases. Thus, some workers who were previously retired have chosen to return to work because they simply cannot afford to live on only social security or pension benefits.

Fig. 4. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Note that this graph shows the change in CPI-U from 2000 to 2021 so as to illustrate rising levels of inflation. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics defines CPI-U as the monthly measure of the average difference over time in prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.

To read more about labor trends among young people and the implications of the aging workforce, see Part Two.

About the Author: Sarah Delano is a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern at the Pioneer Institute for the summer of 2023. She is a senior studying Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.