Boston’s housing boom needs a region-level response

In 1912 – the same year the Titanic sank and William Howard Taft was elected president – a Brookline lawyer, Daniel J. Kiley, wrote a bill for the Massachusetts state legislature that would have annexed 32 cities and towns – including such disparate communities as Lynn, Wellesley, and Weymouth – to the City of Boston. Kiley was part of an entire movement of urban policymakers who thought it was imperative to the Boston region’s economy to facilitate the coordination of each town’s government institutions. At an extreme, this meant annexation.

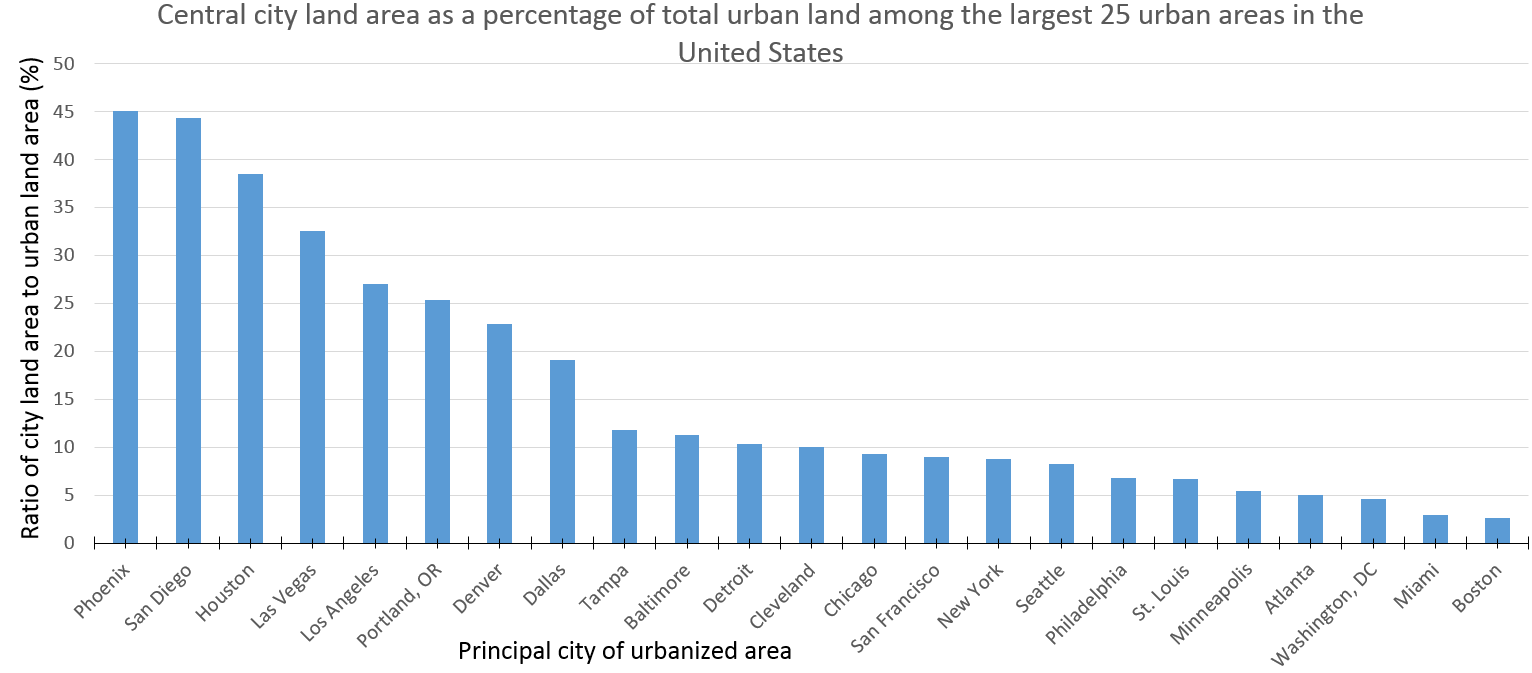

Boston’s (short) annexation history is quite unique in the context of older American cities. As a result, the region is well-connected economically, but divided into far more individual municipalities than one would expect. In Figure 1, I compare the ratio of central cities’ land area to that of the entire urbanized area, as defined by the Census Bureau. Among the 25 largest urban areas in the United States, Boston has the smallest percentage of land area under the jurisdiction of the principal city (2.6%).

Figure 1:

Needless to say, Kiley’s plan failed, largely because of anti-Irish racism, but also because suburban residents didn’t think the City would take their interests to heart. Today, anti-Irish bigotry is probably more prevalent on SNL than in municipal governance, but concerns over urbanization in residential communities are alive and well.

At a time when Boston has undergone an enormous housing boom, prevailing anti-urbanization and anti-development attitudes urgently need to be addressed. Instead of improving the wellbeing of long-time residents, Boston has recently simply replaced them with new, wealthier residents. Because of the high degree of connection afforded by the region’s transportation system and economy, this gentrification pressure spills over into neighboring suburban communities as well.

But already-wealthy suburban communities don’t usually feel the same obligation to meet that demand for housing, citing the aesthetic appeal and character of their towns as integral to their identities and prosperity. In fact, 9 of the 32 communities that would’ve been a part of Boston under Kiley’s annexation plan have at least one of three infamous zoning practices: outlawing multifamily housing, requiring lots of over 1 acre for multifamily developments, or restricting who can live in certain developments by age. The first two essentially limit the proliferation of affordable housing, while the latter helps prioritize housing for downsizing Baby Boomers over that of low-income families. Eventually, this results in segregation by both race and income as affordable housing is concentrated in the few communities that are marginally more tolerant of it.

If the Boston region as a whole does not meet the demand for housing at all, then the economy will face shortages of blue-collar construction and service workers, which are especially needed for infrastructure projects and health care, respectively. Not only does this shortage have ripple effects on the performance of the economy as a whole, but it also offends the sense of justice that comes when a region is able to provide lower-income people with sufficient amenities to thrive.

Luckily, the City of Boston has been aggressively pursuing this fair housing initiative. The current administration seeks to increase the City’s housing stock by 20% by 2030. Mayor Walsh’s plan concentrates development on the periphery of the City proper, however, in neighborhoods like Allston-Brighton, Dorchester, and East Boston. The affordability of some neighborhoods close to downtown Boston, such as Beacon Hill, is considered far gone.

If Boston was a sprawling metropolis of 327 square miles (as it was in Kiley’s 1912 proposal), Mayor Walsh would have a lot more flexibility with the implementation of this plan. The region could respond to the housing boom in a way that truly serves the greater good, however that may be. Instead, wealthy towns have strict zoning codes that limit the capacity for affordable housing development and handicap the national economy while simultaneously tolerating wasteful teardown practices and mansionization. The slightest inkling of urbanization is met with stark opposition.

Strict zoning codes and NIMBYism in wealthy towns contribute to rising costs of living and housing shortages across the entire region. If Boston’s housing boom continues, Boston may be the next San Francisco in terms of affordability. Solutions to this issue need to transcend policy: it is about the culture of excess and entitlement in suburban living just as much as it is about the reform of zoning laws and development practices.

Andrew Mikula is a rising senior at Bates College majoring in economics. Since joining Pioneer Institute as the Roger Perry Government Transparency intern, he has focused on using Pioneer’s MassAnalysis database to analyze social and economic issues. He aspires to be an urban planner upon graduation.