Will the COVID-19-related economic recession cause a spike in crime?

Intuitively, it makes sense that people replace legitimate business with theft and fraud during desperate times. Many police agencies reported rising instances of robbery, burglary, and motor vehicle theft as a result of the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Some publications have even suggested that those who finish their education during economic recessions disproportionately become career criminals rather than gain legitimate employment.

Other observers dispute the link between unemployment and crime, suggesting there are factors underlying increases in unemployment (like a drug abuse epidemic) that better explain the correlation and notable exceptions (like the Great Depression) that otherwise debunk it. With almost a decade of post-recession data analysis in the books, it’s clear that crime rates generally decreased in the U.S. during the 2008 financial crisis. This fact begs the question: in terms of criminal activity, will a recession induced by COVID-19 look more like the 2008 crisis, or recessions of old?

There’s some evidence that social distancing helps reduce crime by making it harder for criminals to burglarize homes, engage in gang activity, or commit acts of petty theft. But it could make domestic violence and online black-market operations more prevalent in the short-term.

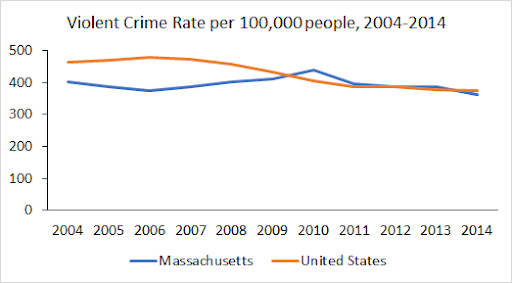

To get the full picture, we need to understand the past relationship between the economy and crime at a deeper level. While it’s true that crime decreased overall in the U.S. during the Great Recession, that wasn’t true everywhere. Using Pioneer Institute’s MassAnalysis data tool, I show that violent crime rates increased in Massachusetts from 2006-2010 (see Figures 1 and 2). Curiously, the same can’t be said for the property crime rate, and the intuition behind the employment-crime link is that hard times lead to stealing, not murder or other violent crimes.

Figure 1: Data shows that, in the face of falling crime rates nationwide, violent crimes increased in Massachusetts during the Great Recession

Figure 2: Property crimes were largely stagnant in Massachusetts during the Great Recession, not significantly different from nationwide trends

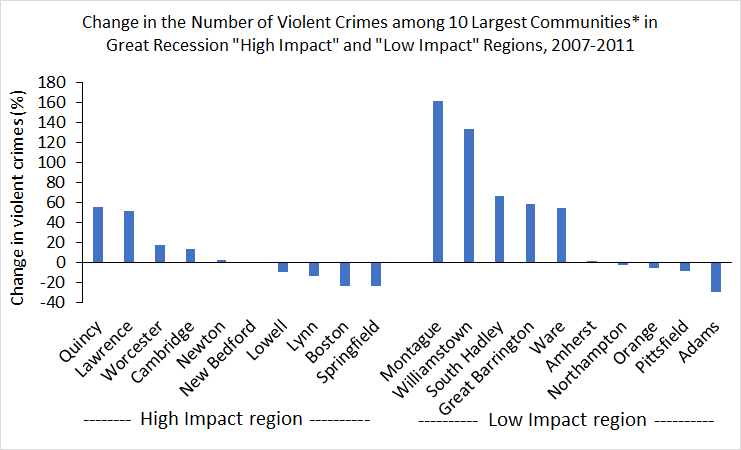

It’s possible that violent crime was rising in Massachusetts in the late 2000s because the recession affected the state more severely than the U.S. as a whole, but that’s unlikely the case. There’s some evidence, however, that the recession was more severe in Greater Boston, Worcester, Springfield, and Cape Cod than in much of Western Massachusetts, Nantucket, and Martha’s Vineyard. If crime and the economy were intrinsically related, we would expect crime rates to rise faster in New Bedford and Lowell than in Amherst and Northampton. Instead, there is little correlation (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Using Census data, I split Massachusetts into two regions based on the Great Recession’s impact on income and poverty. If anything, the Low-Impact Region exhibits more increases in crime over the recession period and aftermath.

*Some communities were excluded because of gaps in the data

With scant evidence that economic growth and crime rates are meaningfully related, COVID-19 likely won’t disturb the persistent decline in U.S. crime rates since the early 1990s. While the cause of the Great Recession (irresponsible mortgage lending) and the current one (a global pandemic) are hard to compare, a recession in which would-be workers practice “sheltering in place” might be more conducive to combating crime. According to Ohio State University economist Bruce Weinberg, “people sitting in their houses don’t make great targets for crime. People going out spending cash and hanging out in big crowds do.”

Andrew Mikula is the Lovett & Ruth Peters Economic Opportunity Fellow at the Pioneer Institute. Research areas of particular interest to Mr. Mikula include urban issues, affordability, and regulatory structures. Mr. Mikula was previously a Roger Perry Government Transparency Intern at the Institute and studied economics at Bates College.