Cape Cod’s Battle Against the Opioid Epidemic

In recent years, opioid-related deaths in Massachusetts have increased much faster than the national average. While steps are being taken to combat the problem, the crisis has challenged all the Commonwealth’s communities. Cape Cod has especially struggled. Of Massachusetts’ 14 counties, Barnstable had the fourth highest opioid overdose death rate of 31.39 per 100,000 people in 2017.

One of the main factors contributing to the development of Cape Cod’s opioid problem was a high opiate prescription rate. In 2012 Cape Cod had an opiate prescription rate about 24 percent higher than the state average. While opioid-related overdose deaths decreased by nearly 19 percent on the Cape from 2016 to 2017, rescuers responded to 15 percent more overdose calls last year than in 2016. Furthermore, between January and March of this year there were more “individuals with activity of concern” in Barnstable County than in any other county in the state. Individuals with activity of concern are defined by the state as patients who have received prescription opioids from four or more providers and had them filled at four or more pharmacies in a three-month period. Barnstable County had the highest rate of these individuals, with 2.2 per 1,000 people, which is more than double most other counties. In fact, about 5.2 percent of the total population of Barnstable County received prescription opioids in the first quarter of the year; 1.5 percentage points higher than the state average of 3.9 percent.

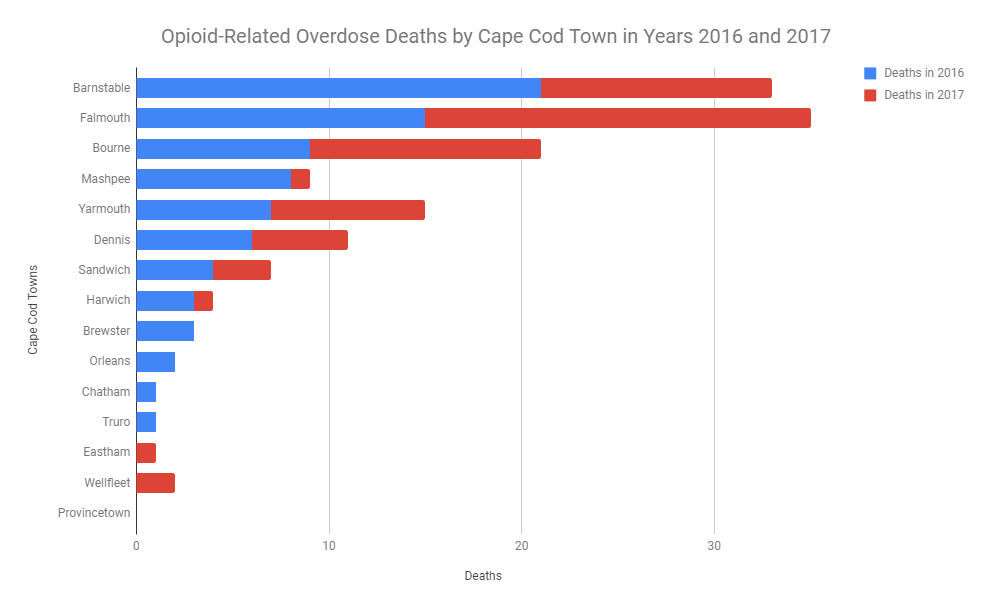

While there are still plenty of initiatives that need to be taken to fight the epidemic, seeing a decline in the opioid overdose death rate last year for the first time in six years is a step in the right direction. Overall, there were 15 fewer opioid-related overdose deaths in 2017 than 2016. And as the chart shows, only four out of 15 towns had more deaths in 2017 than 2016. One of the main reasons that opioid-related overdose deaths decreased is the prescription monitoring program that was launched in 2016. The program tracks prescriptions by patient and includes information on drugs prescribed, the prescriber, and the pharmacy. The program allows a doctor to log on, see a patient’s prescribing trends, and provide information to regulatory and law enforcement agencies if they suspect a patient is seeking opioid prescriptions for non-medical use. The data from the program is used to determine prescribing trends and to provide information to regulatory and law enforcement agencies when necessary. According to Governor Baker, the program puts Massachusetts “Way ahead of where the vast majority of other states are with respect to creating this kind of collaboration…around opioid therapy and addiction management.” In fact, Raymond Tamasi, former president and CEO of the Gosnold Innovation Center, a non-profit innovator in the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders located on Cape Cod, credits the prescription monitoring program for the decrease in opioid overdose-related deaths and also feels Massachusetts has done more than most states in regards to policies addressing health care reform.

Another reason for the decline in opioid-related overdose deaths is extensive use of the reversal drug, Naloxone. U.S. Rep. William Keating has introduced legislation that would direct the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services to “Issue guidelines for prescribing Naloxone in situations involving any type of prescription or illicit opioid use, including heroin or fentanyl.” Experts also attribute the decline in deaths to greater awareness of the problem among prescribers and more collaboration between health care providers and law enforcement.

While the programs in place have been effective in slowing the crisis, additional resources are necessary to end the epidemic. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Elijah Cummings of Maryland are sponsoring the Comprehensive Addiction Resources Emergency Act (CARE), that would distribute $100 billion over 10 years to states to fight the opioid crisis. While states and territories would be given flexibility in terms of how they decide to spend the money, it is primarily for public health surveillance, biomedical research, improved training for health professionals, and increased access to Naloxone. Massachusetts is expected to receive $55 million annually, with the Cape seeing $2.7 million. This funding is necessary, because the vast majority of money spent fighting the epidemic currently goes toward law enforcement, with less than 1 percent devoted to prevention on Cape Cod.

Harris Foulkes is a Pioneer Transparency Intern and is a rising freshman at Amherst College where he plans to study economics.