Op-ed: Let’s return to educational liberty

Read this op-ed in The New Bedford Standard Times, The Lowell Sun, The Fitchburg Sentinel & Enterprise, The Springfield Republican, The MetroWest Daily News, The Providence Journal, The Salem News. The Scituate Mariner, and the NH Union Leader.

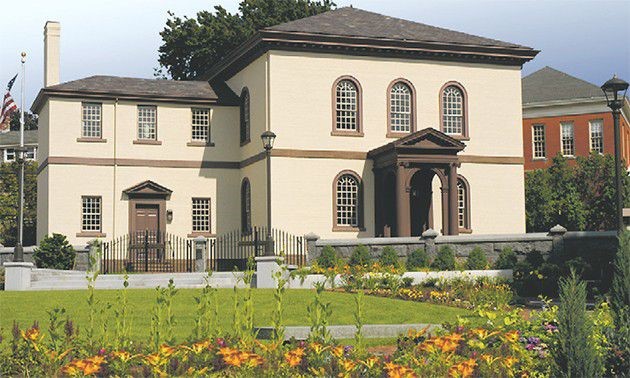

“[T]he Government of the United States … gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance,” President George Washington wrote to the Touro Synagogue congregation of Newport, Rhode Island, in August 1790.

From Washington, D.C., to statehouses across the country, a robust public debate about private and religious school choice is occurring as K-12 education reformers are seeking legal means to expand educational opportunity and bridge socioeconomic achievement gaps in America.

Massachusetts has the best K-12 public, charter, and vocational-technical schools in the country, but also has among the nation’s largest achievement gaps. While the commonwealth’s public school kids perform well nationally, the 67,000 students enrolled in its Catholic schools do even better.

The story of religious liberty, church-state relations, and freedom of conscience on our continent dates back to the colonial era. In 1636, devout dissenter Roger Williams fled intolerant Massachusetts Bay Colony Puritans. He then established Rhode Island as a colony dedicated to religious freedom, or what one scholar termed “the first liberty.”

Like their Pilgrim, Puritan, and later Irish-Catholic immigrant counterparts, who escaped religious oppression in the British Isles, mid-17th-century Spanish and Portuguese Jews came to Rhode Island seeking religious freedom and safe haven from the sectarian bigotry and tyranny they encountered in Europe.

The Founding Fathers’ vision of primary education was grounded in 18th-century religious liberality. Across the early republic, government dollars moved freely between religious teachers, families, and schooling without objection.

Most notably, the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, authored by John Adams, specifically directed localities to fund religious instruction and to have state government underwrite Harvard College, which prepared Protestant ministers. Adams certainly wasn’t the only founder to affirm the public linkage between religion and civic virtue.

“Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds,” President Washington said in his farewell address, “reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

In the Founders’ educationally pluralistic vision, citizens’ receiving a grounding in English, math, science, and history was far more important than whether that education was acquired in a public, private, or religious school setting.

In the 1830s, French commentator Alexis de Tocqueville observed that local civic and religious institutions were crucial to understanding the wellsprings of American democracy.

But in early-1850s Massachusetts, that began to change. Violent nativists, the anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party, passed the nation’s most restrictive “Anti-Aid” amendment, which prohibits disbursement of state and local tax revenues to parochial-school parents. In 1917, another nativist Anti-Aid amendment was passed.

Today, these bigoted amendments serve as legal obstacles to improving urban schoolchildren’s education.

The Know-Nothing, or Blaine amendments, prevent more than 100,000 families in Massachusetts cities with chronically underperforming schools from receiving scholarship vouchers, or education tax credits, that would grant them greater school choice.

These shameful 19th- and 20th-century amendments insult the integrity of our educational system; their infamous legacy endures in the constitutions of 36 other states.

By contrast, Jewish and Catholic groups in Rhode Island and New Hampshire have worked together to establish small education tax-credit programs that fulfill the Founders’ more open-minded vision of religious liberty, while providing under-served kids greater school choice.

If the Bay State repealed our Anti-Aid amendments, which were conceived in prejudice, it would help revitalize our urban educational landscape. In essence, state school funding would follow the student, as it does with government higher education loans across America. Then parents — not the state — could choose from a wide variety of private, parochial, charter, vocational-technical, and religious K-12 school options for their children.

The Founding Fathers established our state and national constitutions to protect, expand, and perpetuate human liberty. As a free and enlightened people, we should be ever wary of public officials who sanction only a rigidly secular view of K-12 education. It’s that illiberal, often anti-religious, attitude that walls off taxpaying religious families and their children from school choices better aligned with what Thomas Jefferson called the dictates of their conscience.

Jamie Gass is director of the Center for School Reform at Pioneer Institute, a Boston-based think tank.