New taxable land parcels are getting very scarce in urban Massachusetts

Plymouth – the oldest town in Massachusetts – has an incredible 2,685 unoccupied plots of taxable land. Meanwhile, Cambridge – a city nearly twice as populous as Plymouth – has just 150. If you know anything about Cambridge and Plymouth, this shouldn’t be surprising. Plymouth is a sprawling coastal suburb with a small, historic downtown. Cambridge is a densely populated urban hub of innovative start-ups, world-class universities, and young professionals with close proximity to Boston.

In creating new development, knocking down trees is a lot easier than knocking down old buildings, and redeveloping old buildings to fit modern uses is especially difficult when there are many other occupied buildings nearby. These realities are clearly reflected in a nationwide pattern of urban sprawl (i.e., building more in places like Plymouth than places like Cambridge). The concern is that urban sprawl creates environmental destruction, health problems, undue burdens on transportation infrastructure, and a host of other maladies.

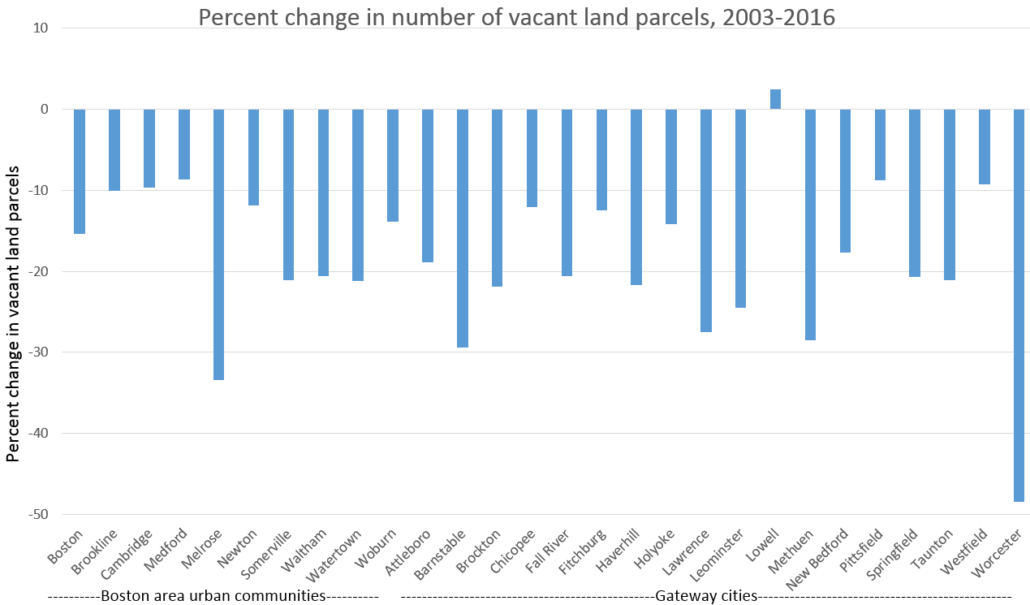

In trying to concentrate development in already built-up areas, some gateway cities have capitalized on opportunities to clean up contaminated land to facilitate redevelopment. However, with Boston’s strong economy and explosive population growth of late, these opportunities are increasingly harder to come by in much of the eastern part of the state. In Figure 1, I compare changes in the number of vacant land parcels over time in both Boston-area cities and gateway communities across Massachusetts. The data comes from Pioneer Institute’s MassAnalysis Metrics tool.

Figure 1:

While gateway cities generally have more pronounced changes in vacant land parcels, the distinction between these changes and those of parcels in Greater Boston is hard to see in the data. Despite the fact that gateway cities often have more brownfields suitable for redevelopment, the economics of the recent housing boom have likely allowed the Boston area to keep pace for now. It’s simply more profitable for developers to build Boston high-rises rather than affordable apartment units in Springfield, thus keeping upward development pressure concentrated near Boston.

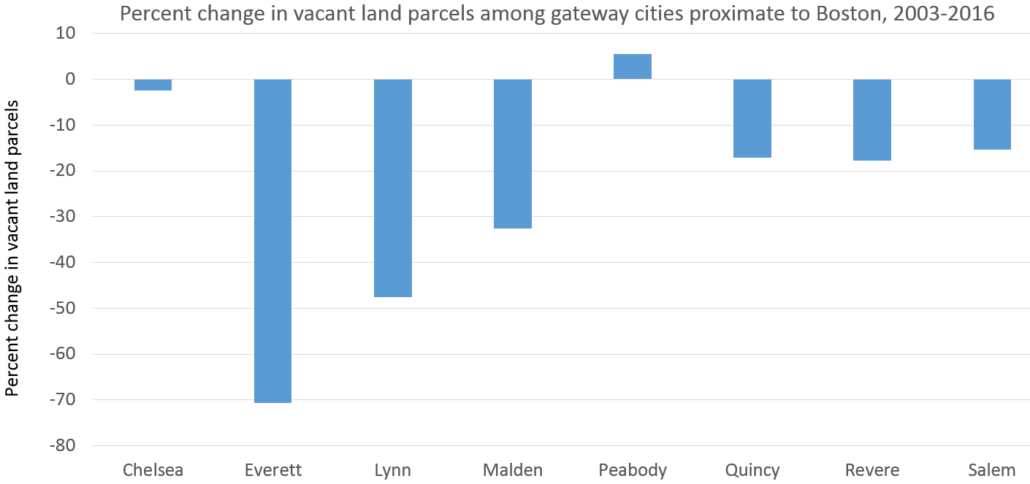

However, Figure 1 omits an important set of municipalities from the data: communities that are both gateway cities and are inside of Route 128. This combination of proximity to Boston and opportunity for infill development seems to allow many of these cities to develop newly taxable land relatively quickly (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Everett, Lynn, and Malden, which all have commutes of under 15 miles to downtown Boston, have experienced a larger drop in vacant land parcels than all but one gateway city (Worcester).

Still, there remains a stark contrast between Boston-area and non-metropolitan towns in terms of parcel development capacity. Becket, Massachusetts, a tiny town in the Berkshires, has more vacant land parcels than it has people. This is also true of two towns on Martha’s Vineyard: Aquinnah and Chilmark. Meanwhile, Everett had the highest percentage drop in vacant land parcels between 2003 and 2016, and now has fewer than two vacant parcels for every 1,000 residents. For Cambridge and Watertown, the corresponding figure is less than 1.5.

As Greater Boston’s real estate market remains hot, developers will have to be more and more creative in finding land in places like Cambridge. Gateway cities will likely have a role in containing the damage of sprawl as people and businesses are priced out of Boston. Otherwise, towns like Plymouth may see development booms of their own.

For more information on tax parcels and land use, explore Pioneer Institute’s MassAnaylsis database.

Andrew Mikula is the Roger Perry Government Transparency intern at Pioneer Institute. He studies economics at Bates College.