Welfare Reform Momentum Must Not Be Stopped

The MBTA’s continuing struggles have dominated local news since February, preventing Governor Baker from pursuing issues of his choice, and those he campaigned on. With last summer’s welfare reform bill awaiting full implementation, Baker should consider shifting focus back onto reforming the Department of Transitional Assistance (DTA).

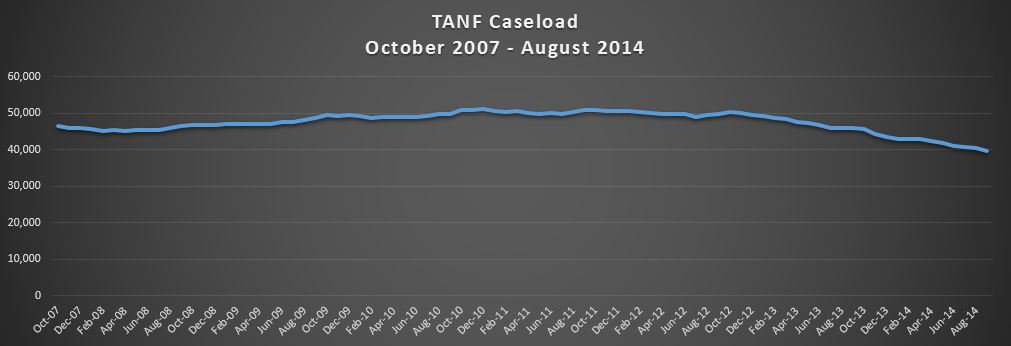

Temporary Assistance to Families with Dependent Children (TAFDC) is the state’s welfare program, and it is currently in a period of transition with new statutes, a new commissioner, and a falling caseload. Since its inception in 1996, TAFDC has significantly reduced Massachusetts’ welfare population, but not without some ups and downs.

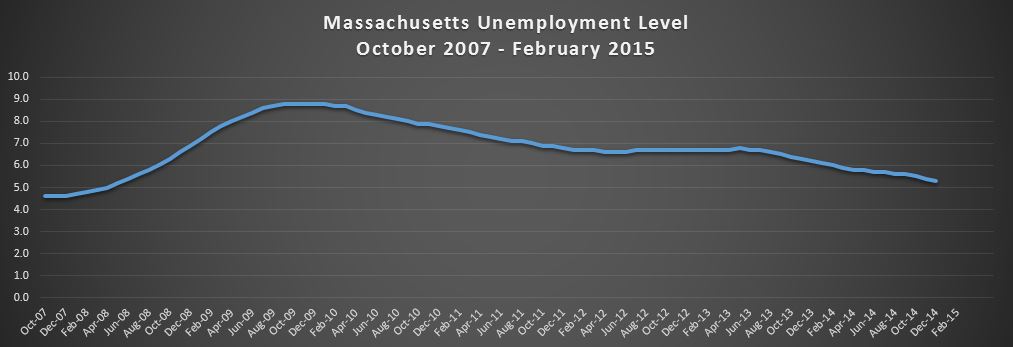

The most recent population peak was in October, 2012 when 50,421 assistance units were reported to the US Office of Family Assistance (OFA). The population has dropped every month since, falling below 40,000 in September, 2014. This drop has coincided with the fall of another important economic metric, unemployment.

Massachusetts emerged from the Great Recession better off than most states, but still required a lengthy recovery. From its peak at the end of 2009 of 8.8 percent, the unemployment rate dropped to 5.3 in the commonwealth by the end of 2014.

The decline in welfare cases began just before the unemployment rate fell from its year-long stagnation at 6.7 percent. As Massachusetts’ economy began to return to healthy employment levels, welfare’s load began to lighten, along with its cost.

The largest line item in the DTA’s budget, TAFDC Grant Payments, is used almost exclusively for cash benefits. In correlation to the caseload decline, the annual budget for this line item has dropped from nearly $316 million in FY12 to only $255 million in FY15. Baker’s proposal for FY16 falls between the House’s recommendation to cut over $33 million and the Senate’s proposed cut of nearly $24 million.

Federal funds for welfare are provided to states contingent on their ability to compel at least half of their recipients to find a job, or participate in job-readiness activities such as training or educational programs. The last time that OFA published national participation data was in 2011 when Massachusetts came in dead last at 7.3 percent.

This was the lowest level that participation had ever reached in the commonwealth, explained by the DTA as the effects of a temporary recipient diversion program. According to the Executive Office of Administration and Finance, in FY14 participation climbed to 58 percent as this problem was addressed, but many questions still remain about the wild swings found in the data.

Last summer, the legislature and Governor Patrick passed a reform bill to address issues such as TAFDC’s loose exemption criteria, a lack of employment specialized workers, and improving access to educational programs. There is significant momentum at DTA to continue strengthening our welfare system, but these measure won’t be enough on their own.

One often overlooked feature of our welfare system is the intake assessment, when applicants meet with a case worker and have a discussion that not only determines whether the prospective grantee is eligible for benefits, but also addresses potentially useful work experience or barriers that might prevent employment.

A skilled case worker can learn a lot about an applicant based on the interview, but according to a 2014 Inspector General report, the assessment is often glossed over and important facts are missed which delay necessary services and can cost the state in the long run.

In 2004, a Welfare Reform Advisory Committee report focused heavily on the initial assessment and the consequences of a poor interview. Nearly half of the report’s recommendations focused on improving assessments. The depth of this issue is brought more clearly into picture in a 2014 report from the Bureau of Program Integrity (BPI) within the Office of the Inspector General.

The BPI found that “the initial assessment of the recipient’s ability to work was limited in scope and not individually tailored to the recipient.” In fourteen of the thirty cases examined during the case review portion of their report, a recipient was sanctioned (punished for non-compliance) and then claimed an exemption from the work program for a disability that existed prior to their initial assessment.

A case worker is tasked with identifying exemptions, such as disability or late-stage pregnancy, during the initial assessment to prevent unnecessary sanctions or referrals that can take months to resolve. Claiming a disability enters the client into a slow verification process that can also take months to complete.

In four other cases pregnant women were not fully screened during their initial assessments and claimed a disability exemption after their child was born, situations case workers were explicitly trained to avoid. In nine of the cases, exemptions from the work program expired, but were not acted upon by case workers until months later.

Many recommendations in the BPI’s report focus on improving the assessment as a tool for case workers to better serve grantees. Case workers are supposed to continue assessing clients throughout the duration of their welfare benefits. The BPI found that ongoing assessment of clients is also an area that needs work:

“In the Bureau’s sample of TAFDC cases, case managers did not conduct thorough initial assessments or reevaluations, and case narratives lacked adequate background information on recipients’ abilities and barriers. Planning and problem-solving are key elements of successful outcomes for recipients but the Department’s case records reflected limited engagement with recipients at key transition points. In general, there was a greater emphasis on administrative work than direct engagement with recipients.”

Studies have shown that the welfare reforms of the 1990s succeeded in helping many find long term employment, but those that remain are often the hardest to employ. In 2002, nearly half of welfare recipients nationwide had two or more barriers to work, such as lack of high school education, language obstacles, or a disabled child.

It’s time to bring the social work aspect back into our welfare system by strengthening initial assessments and allowing case workers to focus on fewer clients with more individualized attention. The timing is optimal considering the welfare reform bill’s revival of the Full Engagement Worker (work specialized case workers), the abolition of the 60 day period for self-directed job search following the initial assessment, and a knowledgeable governor who formerly served as Secretary of Health and Human Services.

Governor Baker must make a decision this summer about whether to reapply for a controversial annual waiver from the work requirements for the roughly 90,000 able-bodied adults on SNAP (formerly called food stamps). These individuals have not had to meet a basic work requirement after three months on SNAP, like they have had to in the past. Baker must shift his gaze towards DTA anyway, but a thorough and complete series of reforms could do wonders for the commonwealth’s poorest.

Initial assessments are key to engaging welfare recipients and keeping them motivated. When a family is looking for benefits they need help now, not in two months when their case worker has time to perform a proper assessment. Anybody who recognizes their need and asks for help deserves the utmost attention and care to facilitate a path towards self-sufficiency.

Too often in politics a job is left half-done, but Governor Baker can assure that the DTA does not meet this fate by following through on his campaign promises to sure up our welfare system. A drop in assistance units coupled with a strong economy and recent reforms sets Massachusetts up to regain its place as a national leader in welfare policy and success.

Scott Haller is a student at Northeastern University working at Pioneer Institute through the Co-op Program.