Study: Refocus on Workfare to Lift Mass. Residents from Poverty

Two decades after welfare reform, only 7.3 percent of Mass. recipients are participating in workfare, compared to the national average of 29.5 percent; Mass. has the lowest rate among the 50 states and Washington, D.C.

BOSTON – During the 1990s, Massachusetts led a welfare reform revolution. A key pillar of that groundbreaking reform was workfare – giving able-bodied recipients the tools to become self-reliant by making work a condition of receiving benefits. For a decade, workfare was a central part of Massachusetts’ continued efforts to truly make welfare a vehicle to transition to the mainstream economy.

But a new Pioneer Institute study, Rebuilding the Ladder to Self- Sufficiency: Workfare and Welfare Reform, shows that today, the commonwealth has the lowest workfare participation rate in the nation.

Rebuilding the Ladder to Self- Sufficiency: Workfare and Welfare Reform

Report co-authors Gregory Sullivan and Charles Chieppo provide a useful review of the history of the welfare reform initiative. They note that the Massachusetts’ reform allows recipients, with several categorical exceptions, to collect benefits for a maximum of 24 months in any 60 month period. It also includes a work requirement of at least 20 hours per week within 60 days of beginning to receive benefits (and for those needing it child care to support their efforts). Those unable to find work must perform at least 20 hours per week of community service.

The result was that welfare rolls dropped by more than half – and stayed down through good times and bad. In 1995, Massachusetts’ welfare caseload was 103,000 families and 273,000 individuals. By 2005 the rolls were down to 46,000 families and 80,000 individuals.

State and federal taxpayers, who invested $706 million in the old AFDC program in fiscal 1994, were by fiscal year 2011 investing $315 million (a 55 percent drop in nominal dollars and a 70 percent drop in real dollars). Importantly, indicators of well-being like child poverty rates dropped even as the welfare rolls dwindled.

As part of the 1996 federal reform, states received federal block grants to advance the goals of the new Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) program, as long as they maintain specific funding levels. The federal law includes “caseload reduction credits” under which states can reduce their work participation requirement by one percentage point for each point drop in the average monthly welfare caseload.

No state has been more aggressive in using caseload reduction credits to demote an emphasis on workfare than Massachusetts. As Figure 1 (TANF Work Participation Rates, 50 States, FY11) shows, by fiscal year 2011, the latest year for which data is available, only 7.3 percent of Massachusetts welfare recipients were working. (The 2011 national average was 29.5 percent.) The commonwealth had the lowest work participation rate among the 50 states and Washington, D.C. Massachusetts’ workfare participation rate also declined more than in any other state.

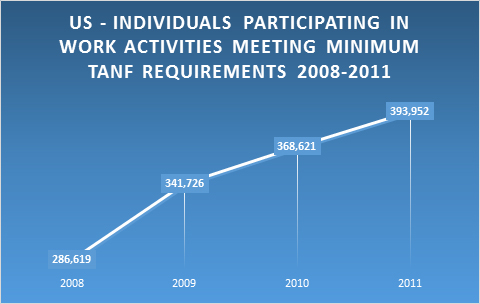

Almost two decades after welfare reform, workfare only nominally continues in Massachusetts, with only 2,732 work-able TANF recipients meeting minimum workfare requirements in fiscal 2011, down from 18,203 in fiscal 2009. Nationwide, the number of work-able TANF recipients meeting minimum workfare requirements increased between fiscal 2009 and fiscal 2011, from 275,943 to 306,495.

Given the results of a 1999 study by the Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance showing that workfare and welfare reform had triggered a substantial decline in child poverty, the subsequent phasing down of the program means the commonwealth hasn’t done enough to lift residents from poverty. Elected officials and policymakers must once again make transitional assistance a priority.

About the Authors:

Gregory W. Sullivan is Pioneer’s Research Director, and oversees the Centers for Better Government and Economic Opportunity. Prior to joining Pioneer, Sullivan served two five-year terms as Inspector General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, where he directed many significant cases, including a forensic audit that uncovered substantial health care over-billing, a study that identified irregularities in the charter school program approval process, and a review that identified systemic inefficiencies in the state public construction bidding system. Prior to serving as Inspector General, Greg held several positions within the state Office of Inspector General, and was a 17-year member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. Greg is a Certified Fraud Investigator, and holds degrees from Harvard College, The Kennedy School of Public Administration, and the Sloan School at MIT.

Charles D. Chieppo is Pioneer Institute’s Senior Media Fellow. Previously, he was policy director in Massachusetts’ Executive Office for Administration and Finance and directed Pioneer’s Shamie Center for Better Government. While in state government, he served as vice chair of the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority. He is also a research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, where he writes for Governing.com’s “Better, Faster, Cheaper” blog. He is a weekly commentator on WGBH, and his work has appeared in numerous publications, including The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe, Boston Herald, Boston Business Journal, Providence Journal, Springfield Republican, Worcester Telegram & Gazette, Washington Times, Education Next, City Journal, and CommonWealth magazine.

About Pioneer

Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government.